Japanese Public Opinion on Constitutional Revision in 2016

This blog post is co-authored by Masatoshi Asaoka and Ayumi Teraoka, an intern and a research associate for Japan studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. This is part of a series entitled Will the Japanese Change Their Constitution?, in which leading experts discuss the prospects for revising Japan’s postwar constitution.

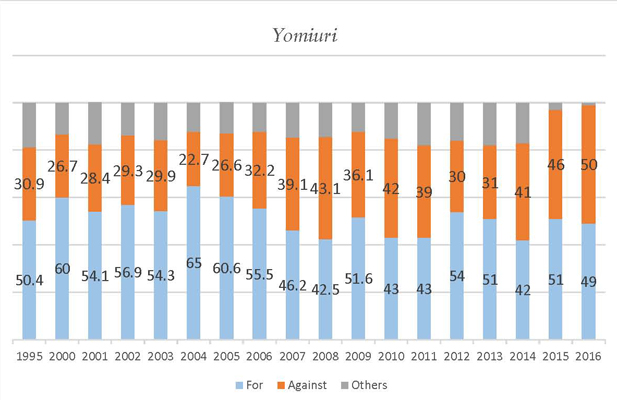

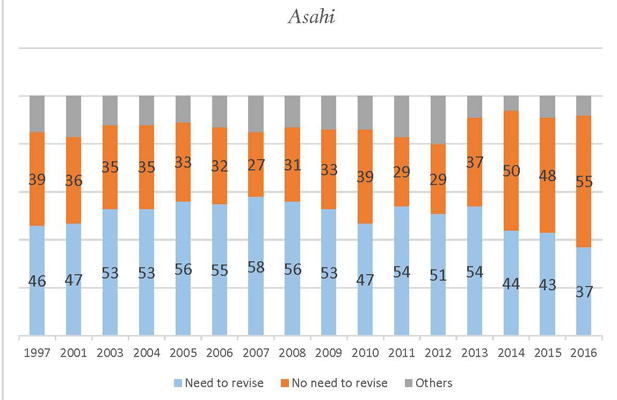

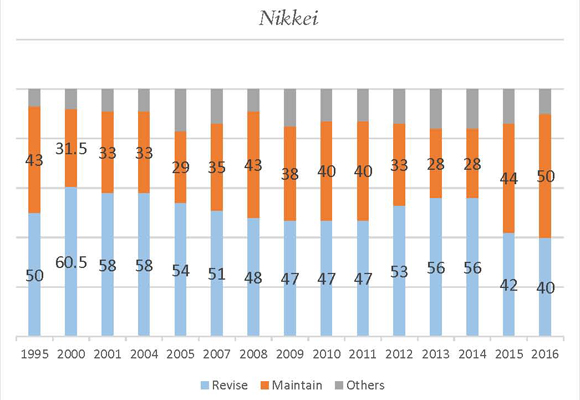

Japan’s politicians seem more likely to debate constitutional revision, but it will be the Japanese people who will ultimately determine the future of their country. As our last blog showed, attitudes toward revising Japan’s 1947 Constitution in the 1950s and 60s were gauged by the Japanese government, but today public polling on the constitution is largely conducted by Japan’s major media outlets. Newspapers have perhaps been the most thorough in trying to understand how the Japanese people are thinking about the prospect of revising their constitution, and survey results from three major newspapers – the Yomiuri Shimbun, the Asahi Shimbun, and the Nikkei Shimbun offer evidence of some interesting trends since the mid-1990s. Each year, these newspapers poll popular views on Japan’s constitution around Constitution Day, a national holiday celebrating its promulgation in 1947.

More on:

But first, let’s take a look at 2016 and how attitudes toward revision related to this summer’s Upper House election.

2016 Polling on Constitutional Revision

In all three major newspaper polls, fifty percent or more of those polled were still opposed to revision of the constitution, revealing that the majority of Japanese are cautious about change despite the effort by politicians to move the debate forward.

The Yomiuri Shimbun poll in March revealed that 49 percent of its respondents supported revision while 50 percent opposed it. The Asahi Shimbun reported in May that 37 percent of its respondents opted for revision and 55 percent were against it. Finally, the Nikkei reported also in May that 40 percent of its respondents were pro-revision while 50 percent were not.

Polling After the July Upper House Election

The Upper House election on July 10 for the first time produced a potential two-thirds majority in favor of a Diet debate over revising the 1947 Constitution. But some polls suggested the Japanese people were more hesitant, and particularly about revising the document under the Abe cabinet.

For example, the Asahi poll on July 14 reported that only 35 percent favored “constitutional revision under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s leadership,” while 43 percent opposed it. Likewise, a Nikkei poll on July 25 found only 38 percent were willing to embrace “constitutional revision under the Abe cabinet” while 49 percent did not.

More on:

Yet both the liberal-leaning Asahi and the pro-revision Yomiuri polls received more positive responses when they asked the question differently. The July 14 Asahi poll asked if “the debate over how to change the constitution should begin in the Diet session in this coming fall?” 55 percent answered yes. The July 13 Yomiuri poll asked whether people “wish for active debate on constitutional revision in future Diet sessions?,” and 70 percent answered yes. Yet both newspaper polls revealed a roughly similar number of those opposed to even discussing revision: 29 percent of respondents for Asahi and 25 percent for Yomiuri.

What About Article Nine?

The Yomiuri Shimbun has conducted the most extensive and in-depth surveys on the constitution since 1981, with annual polling beginning in 1993. Yomiuri has in fact advocated a national debate on revision, and in 1994, 2000, and 2004, the paper even published its own drafts of what a new constitution might look like.

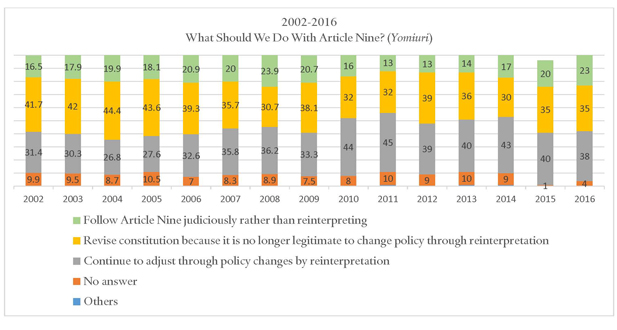

On Article Nine, the Yomiuri polls reveal, however, that its respondents are divided over whether reinterpreting the existing constitution is best or whether the time has come to revise it. For those who want to revise the famous “no war” clause, the Yomiuri polls push further to ask how to phrase a new draft, and implicitly how to refer to Japan’s existing military forces.

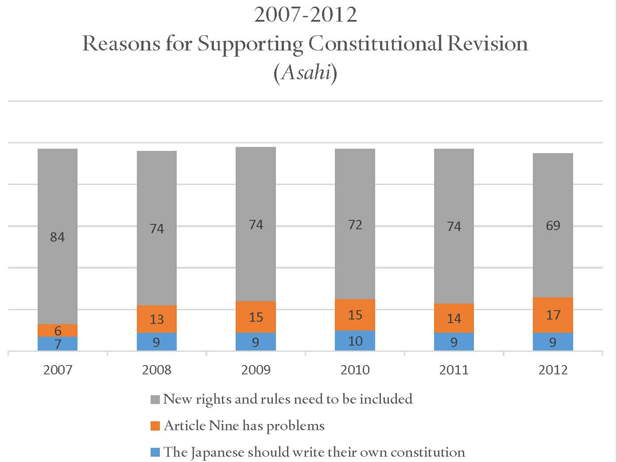

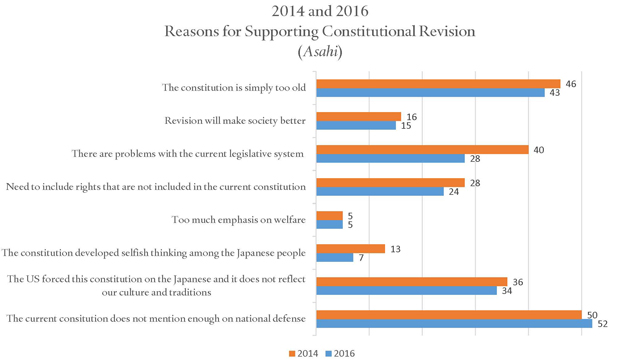

The Asahi Shimbun, on the other hand, has long reflected the views of Japan’s liberals. Asahi polling on the constitution is available online from 1983, and focuses on protecting individual rights. It was only in 2014 that the Asahi introduced questions in its polls on Japan’s national defense needs. Some Asahi respondents express pro-revision sentiments, but the impetus for revision tends to focus on rights protections rather than Article Nine revision. Nonetheless, since Asahi changed the format of their annual polling in 2014, the majority of pro-revision respondents in 2014 and 2016 cited the need to address the lack of reference in the current constitution on national defense.

Polling Results Over Time

These annual surveys by Japan’s newspapers allow us to look at the longer-term trends in popular thinking about Japan’s constitution. Three conclusions can be drawn. First, the Japanese people remain divided on the idea of revising their existing constitution, just as they were in the early-postwar years. Second, the Abe cabinet has dampened the enthusiasm of some Japanese for revision. Strikingly, all of these surveys revealed that more people supported constitutional revision during the 2000s, but support has noticeably declined over the last couple of years—when the Abe cabinet reinterpreted Article Nine and passed new security legislation in the Diet.

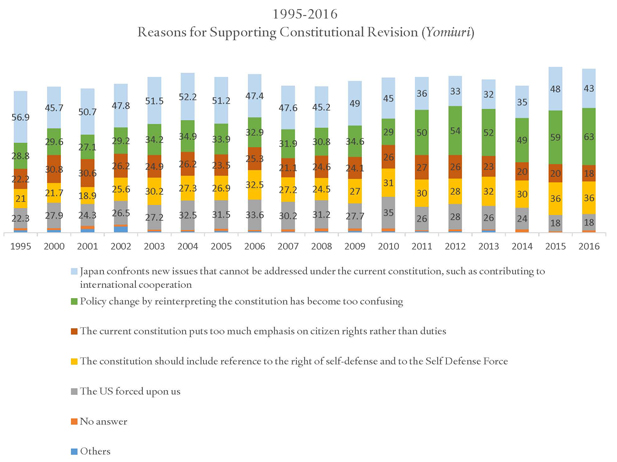

Finally, for those who seem ready for a revision debate, Japan’s liberals and conservatives offer very different reasons for revision. While the more detailed Asahi and Yomiuri polls ask their questions slightly differently and offer different choices in answers, their respondents reveal distinctly different priorities. Most Yomiuri respondents claim that revision is necessary because “adjusting by reinterpretation and implementing changes only causes confusion,” and twice as many Yomiuri respondents selected this choice in 2016 compared with 1995. In contrast, while Asahi poll respondents also increasingly support revision, a growing majority of those who favor revision do so in order to “include clauses on new rights and institutions” (from 69 percent in 2007 to 84 percent in 2013). What is clear, however, is that unlike the cabinet polling of the early postwar decades, far fewer Japanese argue for revision based solely on the origins of their constitution.

Despite this growing interest in discussing revision, both polls still show the vast majority of Japanese do not want to revise Article Nine. In 2016 polls, Asahi still reported 68 percent against revising Article Nine (27 percent would revise it). Yomiuri polls presented more nuanced views. 82 percent would not revise Article Nine’s first paragraph, which commits Japan to not use force to settle international disputes. But far more Yomiuri respondents were interested in revising the language of the second paragraph, which says Japan will not maintain military forces. 48 percent were for and 48 percent were against rewriting Article Nine’s second paragraph.

Yet those who oppose touching Article Nine, both Asahi and Yomiuri respondents rationalized their choices in very similar language: Asahi respondents opposed to revise “because [the constitution] has brought peace”; Yomiuri respondents opposed revision “because it is a world-renowned peace constitution.”

<Yomiuri, Asahi, and Nikkei’s polling data from 1995-2016>

Conclusion

Just like during the 1950s and 60s, the public has been fairly split over this question of constitutional revision over the past two decades. Despite the clear difference over the framing of questions between the liberal and conservative newspapers, both respondents shared mixed feeling about revising their constitution. Strikingly, as the debate gains more momentum in both political and public sphere given the results of the last election the percentage of opposition to constitutional revision in all three surveys marked the highest this year. The future trajectory of this trend is unclear, but what is clear is that that the time is ripe for serious debate over how to shape their own constitution.

Third in a three part series on Japanese public opinion on constitutional revision.

Online Store

Online Store