Informing U.S. engagement with the world

The AI Sovereignty Paradox at Home and Abroad

By Michael Froman

![Alan Cullison featured in front of a blue graphic design background.]()

![An Iranian woman holding a poster depicting Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei walks under a large flag during the forty-seventh anniversary of the Islamic Revolution in Tehran, Iran on February 11, 2026. Majid Asgaripour/West Asia News Agency via Reuters]()

![Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte visit a makeshift memorial for fallen Ukrainian defenders in Kyiv, Ukraine. Ukrainian Presidential Press Service/Reuters]()

![Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Dan Caine speaks during a press conference with U.S. President Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago club on January 03, 2026, in Palm Beach, Florida.]()

America’s Digital Empire Has a Trust Problem

By Kat Duffy

![A large colorful sculpture of the Google logo on display at the AI Impact Summit, in New Delhi, India.]()

CFR Spotlights

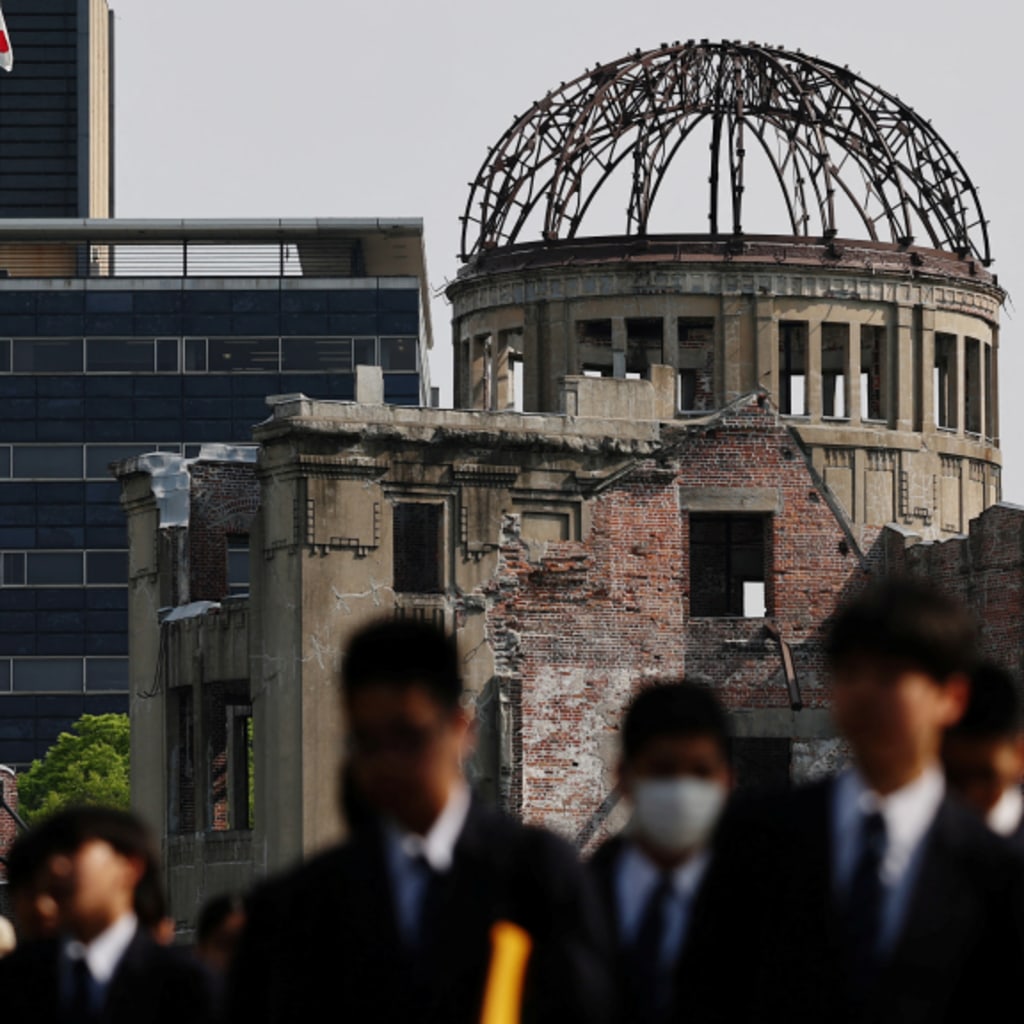

The War in Ukraine

Russia’s invasion has reshaped European security, strained Western alliances, and tested the limits of international resolve. But, as the conflict enters its fifth year, the terms of any eventual settlement appear to remain as contested as the front lines themselves.

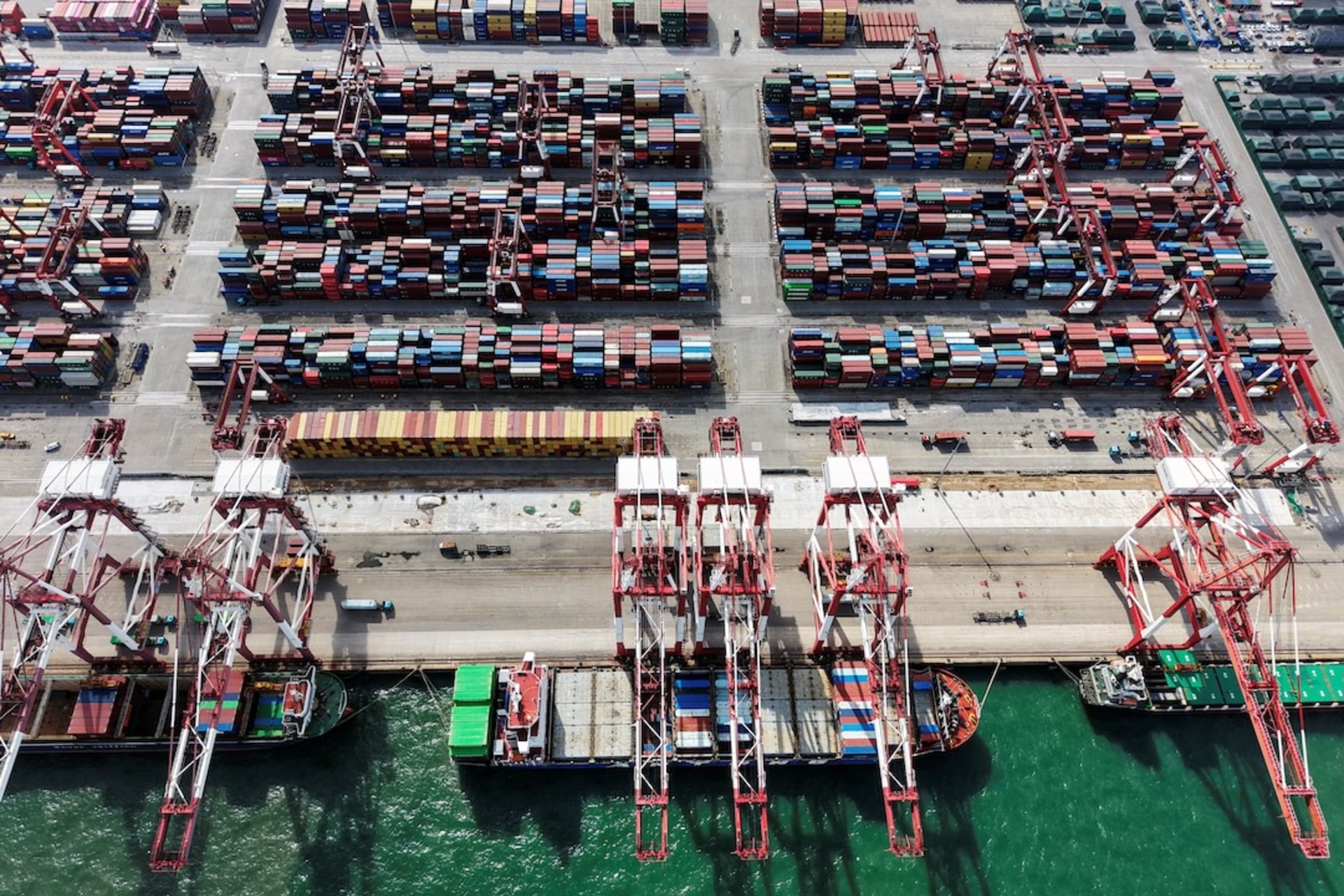

Trade and Tariffs

A landmark Supreme Court decision striking down the president’s use of emergency powers to impose tariffs has upended the legal foundation of Trump’s trade agenda — forcing a reckoning over which tariff authorities remain viable and what comes next for U.S. trade policy.

The World, Explained

Use CFR’s backgrounders and explainers to dig deeper into critical global issues.

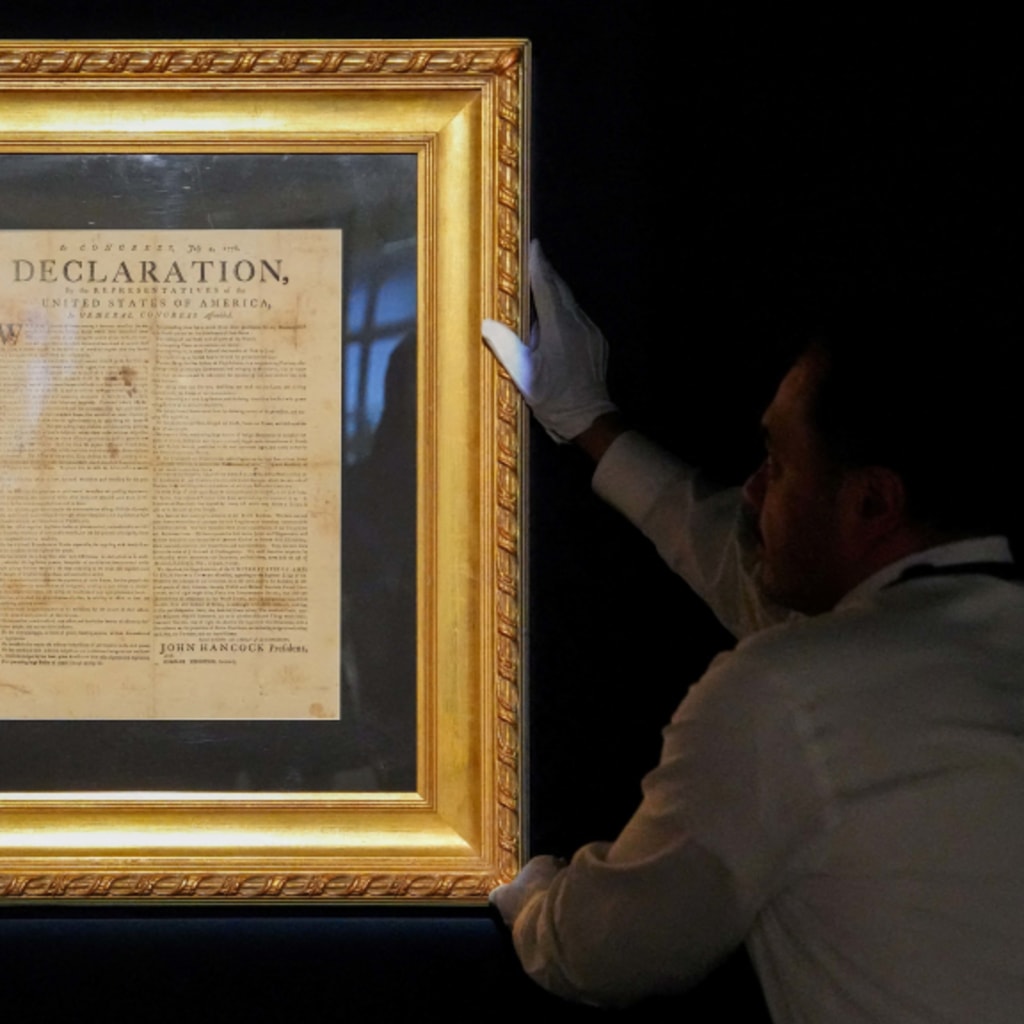

The Spillover Podcast: Trump’s Tariffs Struck Down

The Spillover, CFR’s new weekly series, traces the ripple effects of global events across geopolitics, economics, technology, and finance. In a special episode, host Rebecca Patterson is joined by CFR President Michael Froman, a former U.S. trade representative, to unpack Friday’s Supreme Court decision that struck down Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose tariffs.

Follow on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube

Newsletters

The Daily News Brief

CFR Events

View AllCFR in the News

View AllPublications

CFR publishes reports and papers for the interested public, the academic community, and foreign policy experts.