The Outer Space Treaty’s Midlife Funk

The following is a guest post by Kyle Evanoff, research associate in international economics and U.S. foreign policy at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Outer Space Treaty’s entry into force. The UN agreement, which took effect on October 10th, 1967, created a binding legal regime for the cosmos (Earth notwithstanding). Declaring outer space to be the “province of all mankind” and dictating that it be used for peaceful purposes, the treaty eased U.S.-Soviet tensions, helping to lay the groundwork for the détente of the following decade. The agreement was, in many respects, a triumph for multilateralism.

More on:

Half a century later, however, the Outer Space Treaty has entered something of a funk. Despite the universal aspirations of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, which molded the document into its completed form, many of the principles enshrined within the text are less suited to the present than they were to their native Cold War milieu. While the anachronism has not reached crisis levels, current and foreseeable developments do present challenges for the treaty, heightening the potential for disputes.

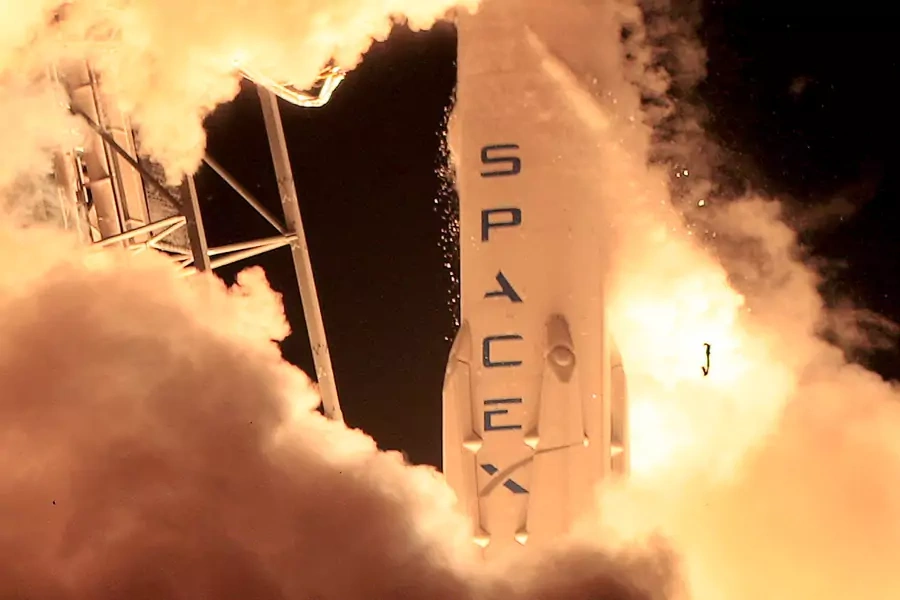

At the crux of the matter is the ongoing democratization of space. During the 1950s and ‘60s, when the fundamental principles of international space law took shape, only large national governments could afford the enormous outlays required for creating and maintaining a successful space program. In more recent decades, technological advances and new business models have broadened the range of spacefaring actors. Thanks to innovations such as reusable rockets, micro- and nanosatellites, and inflatable space station modules, costs are decreasing and private companies are crowding into the sector.

This flurry of activity, known as New Space, promises nothing less than a complete transformation of the way that humans interact with space. Asteroid mining, for example, could eliminate the need to launch many essential materials from Earth, lowering logistical hurdles and enabling largescale in-space fabrication. Companies like Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries, by extracting and selling useful resources in situ, could help to jumpstart a sustainable space economy. They might also profit from selling valuable commodities back on terra firma. As a recent (bullish) Goldman Sachs report noted, a single football-field-sized asteroid could contain $25 to $50 billion worth of platinum—enough to upend the terrestrial market.

With astronomical sums at stake and the commercial sector kicking into high gear, legal questions are becoming a major concern. Many of these questions focus on Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits national appropriation of space and the celestial bodies. Since another provision (Article VI) requires nongovernmental entities to operate under a national flag, some experts have suggested that asteroid mining, which would require a period of exclusive use, may violate the agreement.

Others, however, contend that companies can claim ownership of extracted resources without claiming ownership of the asteroids themselves. They cite the lunar samples returned to Earth during the Apollo program as a precedent. Hoping to promote American space commerce, Congress formalized this more charitable legal interpretation in Title IV of the 2015 U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. Luxembourg, which announced a €200 million asteroid mining fund last year, followed suit with its own law in August.

More on:

Controversies like the one surrounding asteroid mining are par for the course when it comes to the Outer Space Treaty. The agreement’s insistence that space be used “for peaceful purposes” has long been the subject of intense debate. During the treaty-making process, Soviet jurists argued that peaceful meant “non-military” and that spy satellites were illegal; Americans, who enjoyed an early lead in orbital reconnaissance, interpreted peaceful to mean “non-aggressive” and came to the opposite conclusion. Decades later, the precise meaning of the phrase remains a matter of contention.

While the Outer Space Treaty has survived past disputes intact, some experts and policymakers believe that an update is in order. Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX), for instance, worries that legal ambiguity could undermine the nascent commercial space sector—a justifiable concern. Russia and Brazil, among other countries, hold asteroid mining operations to constitute de facto national appropriation. And while there are plenty of asteroids to go around for now (NASA has catalogued nearly 8,000 near earth objects larger than 140 meters in diameter), more supply-side saturation could lead to conflicts over choice space rocks. The absence of clear property rights makes this prospect all the more likely.

Plans to establish outposts on the moon and Mars present a bigger challenge still. Last week, prior to the first meeting of the revived National Space Council, Vice President Mike Pence described the need for “a renewed American presence on the moon, a vital strategic goal” in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal. His piece came on the heels of SpaceX Founder and Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk’s announcement at the 2017 International Astronautical Congress of a revised plan to colonize the red planet, with the first human missions slated for 2024. Musk hopes for the colony to house one million inhabitants within the next fifty years.

While mining might require only temporary use of the celestial bodies, full-fledged colonies would necessarily be more permanent affairs. With some national governments arguing that mining operations would constitute territorial claims, lunar and Martian bases are almost certain to enter the legal crosshairs. And, even under the favorable U.S. interpretation of the Outer Space Treaty, states and private companies would need to avoid making territorial claims. If viable colony locations are relatively few and far between, fierce competition could make asserting control a practical necessity.

Even so, policymakers should avoid hasty attempts to overhaul the Outer Space Treaty. The uncertainties associated with altering the fundamental principles of international space law are greater than any existing ambiguities. Commercial spacefaring already entails high levels of risk; adding new regulatory hazards to the mix would jeopardize investment and could slow progress in the sector. While the current property rights regime may be untenable over longer timelines, it remains workable for now.

The United States, for its part, should exercise transparency wherever misunderstandings are possible. International cooperation, especially for missions that would establish settlements on the celestial bodies, could preempt accusations of national appropriation while increasing the expertise and resources brought to bear. Likewise, civilian rather than military agencies should operate any permanent crewed installations, so as to alleviate concerns over whether U.S. purposes are in fact peaceful.

After decades of stalled progress, humanity may finally be on the verge of creating a multiplanetary civilization. Extensive off-world operations would open possibilities for scientific exploration, inspire future generations, and provide a life-raft in case of global catastrophe. With the technical and financial barriers to space development falling, policymakers must ensure that laws and treaties help to expand rather than limit the sphere of human activity.

Online Store

Online Store