No Clear Fiscal Deadline, and That’s a Problem

More on:

It now looks likely that the U.S. government will remain shut down until an agreement is reached on the debt ceiling, and that could take several more weeks. Markets are starting to worry---global equities are lower, commodities and other growth-sensitive assets are down, and the dollar is weaker. But market moves so far have been moderate, hardly suggesting panic. The usual interpretation: markets are confident of a deal before the deadline. But when is the deadline? Turns out, it’s uncertain and it’s endogenous, depending importantly on how markets react in coming days.

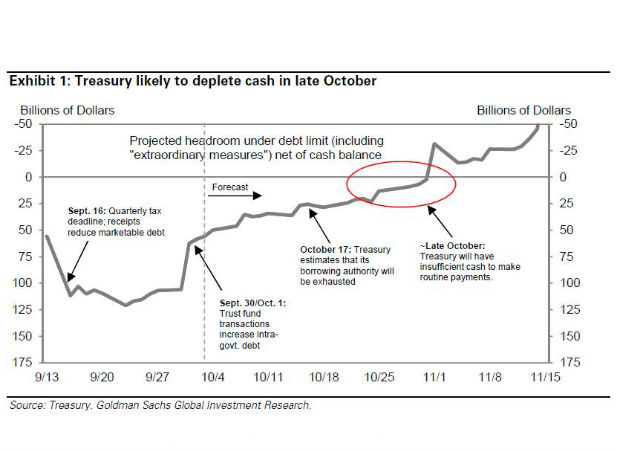

Much of the political commentary focuses on October 17, the day the administration has cited as the date we will hit the debt ceiling. But this is not the day we default; rather it is the date after which the government cannot issue net new debt. After October 17, the U.S. government must pay its bills from its cash balances. Alec Phillips and his colleagues at Goldman Sachs have a great summary of the issues surrounding the looming debt deadline that includes a cash flow projection for Treasury (see chart). Even if the government subsequently runs arrears on some payments, it looks likely to be around November 1 when $60 billion in payments come due that the risk of nonpayment of interest must be confronted. While there are “break the glass” options for pushing back default after that date, it seems most likely that the government would run material arrears in November. Yet, it’s possible in this scenario that debt service would continue to be paid for a while. So the date of default depends importantly on what obligations we are talking about and government policies.

I have little doubt that the votes exist (mainly Democrat) to pass a clean continuing resolution (CR) and clean debt ceiling increase in the House. And I also accept the conventional wisdom that Speaker Boehner will “not allow a default.” But until we reach the 11th hour, both sides will remain locked into hard line positions.

What makes for the 11th hour? What makes it politically unsustainable for one or both sides to hold their hard line? Public reaction to lost benefits and reduced government services are two factors. In addition, most think an adverse market reaction to the risk of default would be a powerful catalyst to getting a deal. Such market pressures have yet to be a forcing factor, for three reasons:

- Markets remain confident that a deal will be reached, and believe that the risk of default is low (lower than many in DC think).

- Consequently, most believe that the effects of the crisis on markets and the economy will be moderate and quickly reversed once a deal is agreed.

- The dislocations caused by the risk of default are complex and subtle (involving the working of money markets and offsetting safe haven effects on longer dated Treasury securities), unlike the sharp TARP-like market reaction that forces action.

So the real deadline for a deal is uncertain and endogenous. It depends on markets, and they in turn will respond to the politics. There is the potential for a misperception spiral here–markets think this will be resolved so they are calmly awaiting political reaction, and the politicians note that markets are calm so there’s no pressing need for action. Perhaps recognition that this standoff can easily go past October 17 will be the trigger that breaks the impasse. But if we go through that date without a deal, and markets remain calm, the politics of a deal may become more difficult. The risk is that the softness of the October 17 deadline breeds an overconfidence that raises the risk of an accident.

I still believe that the way out is a short-term, clean CR/debt ceiling increase coupled with agreement to negotiate the budget for the remainder of the year, with an automatic debt limit increase tied to the results of this new “super committee.” That negotiation would allow for a modest easing of the sequester for FY14 (something a majority in both parties say they want) in return for small future cuts to entitlements. Reports like the 60 Minutes segment last night on social security disability abuse and the fund’s looming funding problem perhaps shows that the debate is shifting away from Obamacare to a broader debate over entitlements and the critical need for reform (but also the political sensitivities involved).

More on:

Online Store

Online Store