- China

- RealEcon

- Topics

-

Regions

FeaturedThe 2021 coup returned Myanmar to military rule and shattered hopes for democratic progress in a Southeast Asian country beset by decades of conflict and repressive regimes.

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

Featured

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

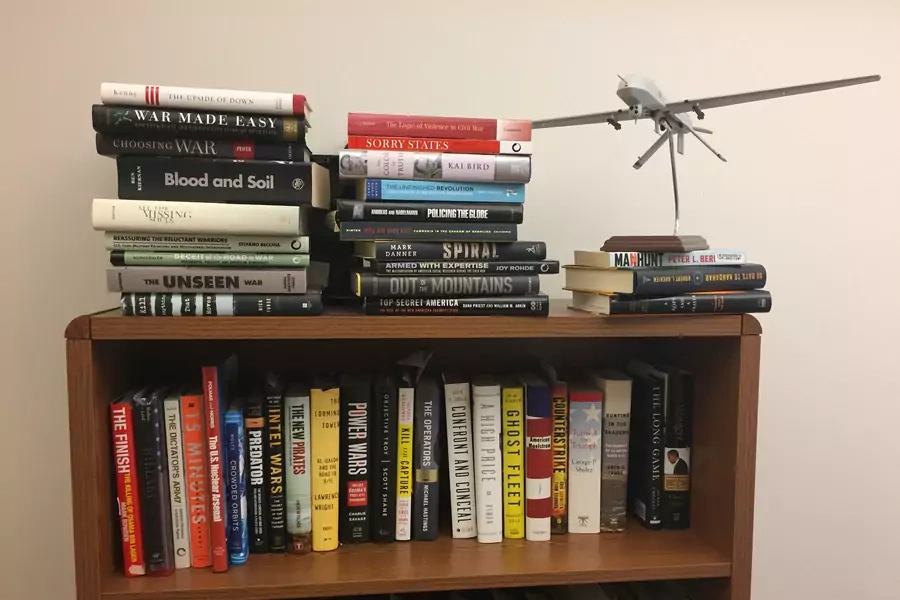

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

How the Pentagon Announces Killing Terrorists Versus Civilians

This blog post was coauthored with my research associate, Jennifer Wilson.

Last week, the U.S. military announced an accomplishment that has come to define progress in the war on terrorism—the death of yet another senior terrorist leader. These now-routine reports are touted by officials as bringing “justice” to terrorists, delivering a “significant blow” to their ability to maneuver and operate, and even "eradicating" the threats they pose.

On Friday, a spokesman for U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), Colonel John Thomas, told reporters that special operations forces had killed “a close associate” of the leader of the self-proclaimed Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. This announcement came fifteen days after the ground raid that killed him on April 6—coincidentally, the same day as President Donald Trump’s cruise missile strike on an airfield in Homs, Syria.

As the United States ramps up its airstrikes and targeted raids against the Islamic State in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, there has been a corresponding increase in reported civilian casualties. Airwars estimates that at least 3,111 civilians have been killed in U.S.-led coalition airstrikes since the anti-Islamic State air campaign began in August 2014. However, CENTCOM implausibly assess that “at least 229 civilians have been unintentionally killed” in all 19,607 strikes.

CENTCOM publishes a monthly civilian casualty report including reported non-combatant casualties found credible (meaning a strike more likely than not resulted in the death or injury of a civilian), those found non-credible (meaning there is not sufficient information to determine whether a civilian was harmed), and ongoing investigations. There are currently forty-three open investigations, one of which has been going on for over a year.

On average, it has taken CENTCOM ninety-five days to announce whether a coalition strike resulted in a civilian casualty over the past six months. Meanwhile, on average, it has taken just eleven days for the Pentagon to announce that a strike has resulted in the death of a “key leader” of a terrorist organization over the past year. (We averaged the time elapsed between the alleged incident and the U.S. military announcement of 115 cases of civilian casualties and 19 announcements of killed terrorists, after removing the highest and lowest number of days passed for both to avoid distorting the mean.)

We can only speculate why there is such a vast disparity between the time it takes to investigate the death of a civilian versus the death of a terrorist. However, what this inconsistency demonstrates is that publicizing the deaths of terrorists is a higher priority for the U.S. military than determining the deaths of civilians. For example, last week, a coalition spokesperson, Colonel Joe Scrocca, even acknowledged “we don’t have any means of going and searching out people and, honestly, we don’t have the manpower” to conduct rigorous investigations of reported civilian casualties. The Pentagon claims that it “takes all reports of civilian casualties seriously and assesses all reports as thoroughly as possible.” If this were the case, though, then there would be sufficient surveillance and analytical resources dedicated to thoroughly and more quickly investigate reported civilian casualties.

As the former U.S. Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, Lieutenant General Bob Otto (ret.), observed in October 2015, “If you inadvertently—legally—kill innocent men, women, and children, then there’s a backlash from that. And so we might kill three and create ten terrorists.” If Otto’s concerns are to be believed, then investigating claims of civilian harm, holding those in the chain of command responsible to account, and assuring that past errors are not repeated should be as high a priority as is killing yet another in the seemingly inexhaustible supply of senior terrorist operatives. Unfortunately, the military is more committed to boasting about killing alleged terrorists than determining when non-combatants are harmed in the process.

State Death, War Declarations, and Battle Deaths: A Conversation with Tanisha Fazal

I was honored to talk to Tanisha Fazal, professor of political science and peace studies at the University of Notre Dame, about her extensive and impressive body of policy-relevant work. Fazal is a faculty member at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies and a co-director of the Notre Dame International Security Center. In addition to the book State Death: The Politics and Geography of Conquest, Annexation, and Occupation, she is also the author of many excellent works including her more recent article “Rebellion, War Aims, and the Laws of War” and blog post entitled “How Norms Die,” with Seva Gunitsky.

In our conversation, Fazal discusses the international norm against seizure of territory and how it might be changing, and she offers an explanation of why states no longer declare war or conclude peace treaties. We also talk about the policy implications of her findings that war may not actually be on the decline, and what it means that advances in military medicine, while decreasing the number of battle fatalities, have also cause a huge relative increase in the number of battle casualties. These findings counter recent scholarship that relies on battle death trends, and have serious implications for public perceptions of war and casualty aversion.

Tanisha gives advice to young scholars, from what to do before graduate school to how to pick a research question—and the academic utility of getting annoyed. Listen to our conversation, and be sure to follow Fazal at @tanishafazal.

End to Euphrates Shield, but Not to U.S.-Turkey Tensions

Caroline O’Leary is an intern in the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.

On Wednesday, Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim announced the end of Operation Euphrates Shield, deeming the military campaign, which began in August of 2016, a success. The operation brought an armored battalion and supporting ground forces across the border into Syria, the first direct Turkish military intervention into the country. The campaign had two declared objectives: to remove self-proclaimed Islamic State forces from towns along the Turkish-Syrian border towns and to prevent armed Kurdish groups from advancing. Achieving the former clearly helped bring the United States closer to its own goal to “demolish and destroy ISIS.” Turkey’s efforts to stunt Kurdish progress, however, significantly complicate U.S. interests in the region.

The Kurdish groups that Euphrates Shield targeted are the United States’ most effective ground partner in combatting the Islamic State. But these forces also have ties to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which for decades has waged an insurgency against Turkey and is designated as a terrorist organization by the United States, Turkey, and the European Union. U.S. support for the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an umbrella group of mostly-Kurdish forces, has been a sore spot for U.S.-Turkish relations throughout the United States’ involvement in the Syrian civil war. The SDF is made up mostly of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), a PKK-affiliated group that is the dominant Kurdish group in Syria. Though Euphrates Shield is officially over—a development that came just one day before U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s visit to Ankara—tensions over U.S. support for Kurdish groups will remain.

These challenges will need to be addressed as the U.S.-led coalition to counter the Islamic State as well as rebel and Kurdish forces move to take Raqqa, the Islamic State’s de facto capital in Syria. Just last week the United States military airlifted Kurdish fighters as part of a combat operation for the first time, indicating a coming increase in U.S. support for the fighters. Last month, the Center for Preventive Action released a discussion paper entitled “Reconciling U.S.-Turkish Interests in Northern Syria,” which details the competing interests in the region and offers recommendations for the Trump administration. Author Aaron Stein, resident senior fellow in the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East at the Atlantic Council, lays out the strategic options that policymakers have and the risks involved with each.

Given the complexity of the situation, addressing only one aspect of the conflict could undermine long-term U.S. interests in the region. To both improve the U.S. relationship with its North Atlantic Treaty Organization ally, Turkey, and to defeat the Islamic State, Stein recommends that the United States:

Offer to mediate peace talks between the PKK and the Turkish government. Given the U.S. involvement with both Turkey and Kurdish groups, the United States can exercise leverage to negotiate a ceasefire and mediate peace talks.

Quietly indicate support for a decentralized future Syrian state. While this is a politically difficult proposal, “absent a clear articulation of what it is that the United States wants in Syria—besides defeating the Islamic State—the United States will struggle to articulate a viable political solution.”

Utilize any progress from PKK-Turkish talks to instigate ceasefires between the YPG and Arab/Turkmen insurgents. While the United States has little leverage among these groups now, Stein notes that this approach, “in tandem with renewed efforts to work with Russia to broker a Syria-wide cease-fire,” could lead to another round of negotiations. It would also require continued U.S. diplomatic involvement in the conflict.

While Stein acknowledges the competing interests of the actors involved in northern Syria, he advocates for an approach that addresses these conflicts in order to advance long-term U.S. interests in the region. Read “Reconciling U.S.-Turkish Interests in Northern Syria” for an in-depth analysis of U.S. options in northern Syria.

Obama’s Worst Foreign Policy Decision, Two Years Later

You probably missed it, but Saturday was the second anniversary of President Barack Obama’s worst and most indefensible foreign policy decision. Late on the evening of March 25, 2015, the White House posted a statement from National Security Council spokesperson Bernadette Meehan on its website: “President Obama has authorized the provision of logistical and intelligence support to GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council]-led military operations. While U.S. forces are not taking direct military action in Yemen in support of this effort, we are establishing a Joint Planning Cell with Saudi Arabia to coordinate U.S. military and intelligence support.”

With only that quiet statement—and absent a single congressional hearing or any public debate—the United States became a co-combatant in yet another open-ended war of choice in the Middle East. My latest column in Foreign Policy recognizes the two years of U.S. support for the Saudi Arabia-led intervention in Yemen, which has devastated Yemeni infrastructure and killed an estimated five thousand civilians—but has brought Saudi Arabia no closer to defeating Houthi rebels:

As the U.N. Panel of Experts documented in its excellent report released in January, the Saudi-led coalition has violated international humanitarian law and human rights law with its use of air power at least 10 times in 2016. The 10 documented strikes resulted in “292 civilian fatalities, including at least 100 women and children.”

Most horrific was the Oct. 8, 2016, “double-tap” bombing of a community hall in the capital of Sanaa that resulted in at least 827 civilian fatalities and injuries. The airstrike targeted a funeral gathering, first with a U.S.-supplied “GBU-12 Paveway II guidance unit fitted to a Mark 82 high explosive aircraft bomb,” dropped at 3:20 p.m., followed by a second one minutes later as mourners were still reeling. As the U.N. report notes, “the air campaign waged by the coalition led by Saudi Arabia, while devastating to Yemeni infrastructure and civilians, has failed to dent the political will of the Houthi-Saleh alliance to continue the conflict.”

Yesterday, the Washington Post and Foreign Policy reported that President Donald Trump may expand U.S. military support for the Saudi-led bombing campaign. This includes more operational planning, logistics, and refueling support, and may also feature direct support for an Emirati-led ground intervention against a Red Sea port held by Houthi forces. These measures are being debated and approved faster than under the Obama administration because, according to one Pentagon official, the absence of civilian leaders means “the [Pentagon hierarchy] has flattened, so from a military perspective you have a little more agility, and can make decisions more quickly,” adding “the military has a bias to action and we’d rather act than sit there and ponder it forever.” Another senior administration official indicated that the United States must support whatever the Saudi-led coalition does because the situation may escalate, “and our partners may take action regardless. And we won’t have visibility, and we won’t be in a position to understand what it does to our counterterrorism operations.”

Both of these sentiments should be disconcerting given the aimlessness and unfolding tragedy of the two-year, U.S.-supported intervention in Yemen. One would hope that the Trump administration’s rush to further deepen U.S. military involvement in the Middle East would generate interest and criticism among Congress, major media outlets, and the American public. But given the relative free-hand and limited oversight that has come to characterize the United States’ forever war, I would not expect any coherent opposition, or even sustained attention.

Again, for my full thoughts see today’s column, and also what I warned of with a column two years ago: “Make No Mistake — the United States Is at War in Yemen.”

Entrepreneurship, Erdogan, and Interrupting: A Conversation with Elmira Bayrasli

The wonderful Elmira Bayrasli joined me again for discussion that ranged from the rise of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to women’s role in shaping foreign policy. Elmira is a fellow in New America’s International Security program, a professor at NYU School of Professional Studies and Bard College’s Global and International Affairs program, author of From the Other Side of the World: Extraordinary Entrepreneurs, Unlikely Places. (In case you missed it, you can listen to our talk last April about From the Other Side of the World here) She is also co-founder with Lauren Bohn of Foreign Policy Interrupted (FPI), an education and media startup dedicated to increasing female foreign policy voices in the press.

We discussed current Turkish policy and Erdogan’s endgame in Syria, and Elmira provided insights into how populism affects start-ups across the world. She also gave an update on what FPI has been doing lately, including guest-editing the women-authored winter issue of the World Policy Journal, titled “World Policy Interrupted.” Listen to our conversation, and be sure to follow Elmira on Twitter @EndeavoringE.

Online Store

Online Store