- China

- RealEcon

- Topics

-

Regions

FeaturedThe 2021 coup returned Myanmar to military rule and shattered hopes for democratic progress in a Southeast Asian country beset by decades of conflict and repressive regimes.

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

Featured

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

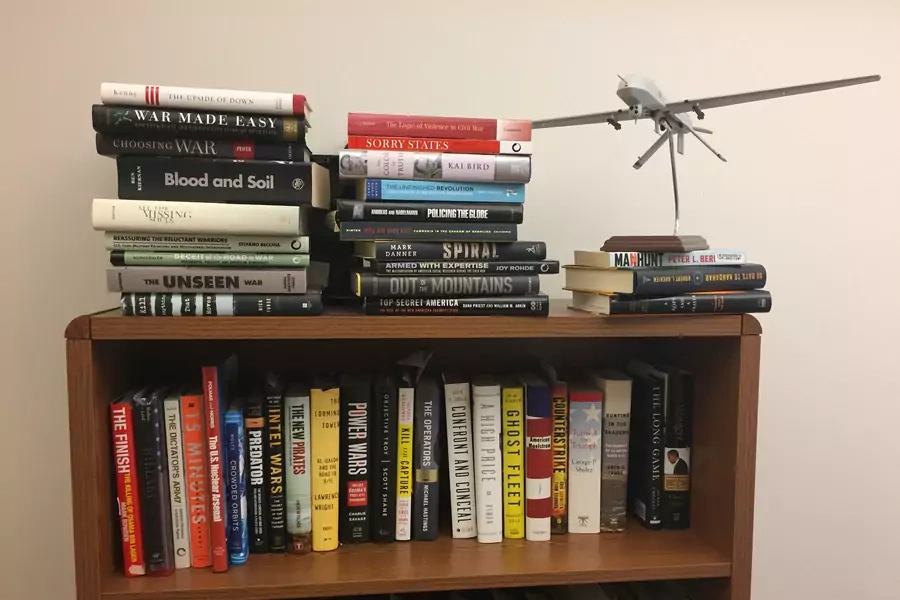

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

Kabila’s Repression: A Consequence of UN Inaction

Susanna Kalaris an intern in the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.

As Americans flocked to polling stations on November 8, United Nations peacekeepers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were hit by a grenade blast that killed one and injured thirty-two others. Since 1999, the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC), and its successor, MONUSCO, have deployed peacekeepers to implement a ceasefire, disarm combatants, and protect civilians following an international war that killed an estimated 5.4 million people between 1996 and 2003 and plunged the country into economic and political chaos. Yet despite more than seventeen years, twelve billion dollars spent, and twenty-thousand personnel dispatched across the country, the peacekeeping missions have left an unfulfilled mandate and a local government that recognizes and profits from its failures. President Joseph Kabila and his government are emboldened to maintain the political status quo; while peacekeeping troops struggle to contain violence, the government violates democratic processes and civil rights with impunity, knowing MONUSCO will not stop it anytime soon.

Like some other notorious UN peacekeeping missions, MONUSCO has failed to intervene as rebel forces attacked civilians and outraged those they are meant to protect. In November 2012, as the M23 insurgent group invaded the city of Goma, fleeing civilians were passed by trucks full of peacekeepers themselves escaping the rebels. M23 troops went on to take Goma without resistance from the better-equipped and more numerous MONUSCO forces. The peacekeepers drew both international and local criticism: France called their actions “absurd,” and young Congolese deemed them “useless” and “dismissed.” During a rebel attack in June 2014, at least thirty civilians were killed in the two days it took for MONUSCO forces to respond to calls for help in South Kivu. In August of this year, rebel fighters massacred at least fifty civilians with impunity, prompting over two thousand protestors to decry the lack of action from MONUSCO.

These instances of inaction have powerful consequences not only for the victims of attacks, but for the future of the DRC. Since succeeding his father in 2001, President Kabila has presided over a government plagued by corruption, instability, and civil rights violations. Between June 2014 and May 2015, the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office reported numerous violations of the rights to free speech and assembly, including suspending opposition radio and television programs and blocking citizens’ access to text messaging and internet services. The government has also used force against opponents, as in January 2015 when national security forces killed at least twenty unarmed protestors. The arrests and deaths of demonstrators and opposition leaders across the DRC foreshadowed Kabila’s latest exploit, postponing presidential elections until 2018 and violating presidential term limits. Political violence has since escalated throughout the country—clashes between police and civilians protesting Kabila’s postponement left seventeen people dead in September.

Critics have explained Kabila’s violation of the constitution and civil rights solely as an attempt to cling onto power, but it can also be considered a result of the inefficacy of MONUSCO forces. MONUSCO’s mistakes set an example of weakness that allows the political climate in the DRC to endure and even worsen, as it has in the past months. The failures of MONUSCO troops to protect the civilian population demonstrate to Kabila and his government that an international force has little power to affect change within his country. Consequently, Kabila is empowered to repress speech, arrest opposition voices, and use deadly force with impunity. As long as peacekeeping troops fail to create positive change in the DRC, the government can continue the current climate of violence and repression can continue without accountability.

While many scholars advocate for better-equipped troops, more specific mandates, or flexible forces in the DRC, what is missing is accountability. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon regularly condemns rebel attacks on civilians, though there is neither criticism nor rebuke for the inaction of peacekeepers and their commanders. A UN Office of Internal Oversight Services report acknowledges several reasons why peacekeepers fail to protect civilian populations, but its few recommendations—like publishing “self-contained guidance” and increasing reporting of failures—lack teeth. Only by holding forces and their commanders accountable with tangible consequences will troops fully commit to their mandates and the populations they are asked to protect. If the UN truly held MONUSCO forces in the DRC responsible, and if peacekeepers fulfilled their mandate, President Kabila and his government would find their impunity greatly curbed and the opportunities to repress democracy interrupted. No longer would their rule be immune to the civil rights and democratic processes that are essential to a lasting peace.

U.S. Airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, Versus Drone Strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia

Yesterday, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) published an updated estimate of civilian casualties from U.S. airstrikes in Iraq and Syria. Previously, the Pentagon had acknowledged just 55 civilian casualties for the air war that began in August 2014. The new CENTCOM estimate listed a total of 24 civilian casualty incidents, which “regrettably may have killed 64 civilians.” This makes the new official estimate of civilian fatalities 119.

During this period, the United States conducted 12,354 airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, which killed “45,000 enemies taken off the battlefield,” according to Lt. Gen. Sean MacFarland in the latest publicly provided body count for the so-called Islamic State (IS).

Thus, using the U.S. government’s data, 12,354 airstrikes over 27 months have killed 45,000 ISIS fighter and just 119 civilians. This means that for every 103 airstrikes there is a civilian fatality, and for every one airstrike there are 3.64 IS fighters killed.

As I have written previously, this claim of nearly infallible target discrimination and weapon precision is simply unbelievable in a combat environment where civilians and combatants are so closely intermingled. IS fighters have employed civilian-designated facilities for its own purposes, and reportedly used human shields in its headquarters sites and during the movement of its fighters. Meanwhile, as noted, U.S. military officials, analysts, and pilots make inevitable human errors of judgment and violate established protocols, resulting in unintentional civilian deaths. It is misleading to believe U.S. airstrikes are so precise.

It is also important to recognize that a “strike” does not mean one single bomb dropped. The definition of a strike used by CENTCOM is, “one or more kinetic events that occur in roughly the same geographic location to produce a single, sometimes cumulative effect for that location.” There was a single “strike” that destroyed 283 IS oil trucks on November 22, 2015, of which the Pentagon released a video. That strike was actually a series of A-10 strafing runs, using depleted uranium rounds, which a CENTCOM spokesperson admitted to reporter Samuel Oakford.

Finally, Amelia Mae Wolf and I demonstrated in April that U.S. drone strikes in non-battlefield settings were far less precise than manned airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, using the best available data at the time—this included non-governmental organizations and the U.S military. Now, we can revisit this claim by exclusively using U.S. government data.

On July 1, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) released a “Summary of Information Regarding U.S. Counterterrorism Strikes Outside Areas of Active Hostilities.” That release claimed that between January 20, 2009, and December 31, 2015, there were 473 strikes that killed between 2,372 and 2,581 combatants and 64 and 116 noncombatants. Therefore, using the average of the range provided by ODNI, 473 drone strikes killed 90 civilians.

Or, 0.19 civilian is killed for every drone strike in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia.

And, 0.009 for every airstrike (almost all are manned airstrikes) in Iraq and Syria.

That means that airstrikes in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia are more than 20 times more likely to kill a civilian than those in Iraq and Syria.

How Everything Became War: A Conversation With Rosa Brooks

I was lucky enough to speak with Rosa Brooks about her recent book, How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales From the Pentagon. Rosa is law professor at Georgetown University, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation, and a fellow columnist for Foreign Policy. We talk about her unique and compelling experiences at the Pentagon, where she served as a counselor to the undersecretary of defense for policy. Rosa also shares her thoughts on the role of retired military officers in election politics, and the difficulties (or lack thereof) in addressing the most pressing challenges to U.S. national security policy and law. She also gives some important advice for young policy professionals starting their careers.

Listen to my conversation with the brilliant and insightful Rosa Brooks, check out her new book (if you haven’t already) and follow Rosa on Twitter @brooks_rosa.

Five Ways Trump’s Foreign Policy Would Be a Disaster

I have a new column today on Foreign Policy—“Trump Is Less Hawkish Than Hillary. Who Cares?”—which summarizes my evaluation of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump’s foreign-policy positions. I have published a number of pieces focusing on both candidates, from Clinton’s call for a no-fly zone in Syria, to Trump’s convenient amnesia about strongly endorsing a U.S. ground intervention in Libya in February 2011. This campaign has been marked more by perceptions of the candidates’ behavior, temperaments, and familial or professional connections than actual policies.

However, based upon the limited and skewed available information about their likely foreign policies, Donald Trump would be a far more dangerous and destabilizing Commander in Chief. He has not demonstrated any improved understanding of the basic principles, laws, and behaviors that govern the foreign policymaking process, nor the manner in which states routinely interact with each other. Far worse is his unwillingness to acknowledge when he has changed his mind, or learned from others. Instead, he has consistently lied about his past positions, and, when asked who he listens to on foreign policy, stated “I’m speaking with myself, number one, because I have a very good brain and I’ve said a lot of things.”

My new column details five consequential foreign policy issues on which Trump has demonstrated his misinformed and dangerous opinions. To take just one example:

Trump either has no understanding of U.S. conventional military power, or is being intentionally misleading about the capabilities of the armed forces. He inaccurately defames the most globally committed and powerful military in world history as being “very weak” and “seriously depleted,” and led by generals who “have been reduced to rubble to a point where it’s embarrassing to our country.” Other than repeating the Reagan “peace through strength” mantra with zero context, Trump has given little indication what sorts of military missions he would support. He opposes using U.S. ground troops for “nation-building,” but has repeatedly endorsed using them in Iraq (and in Libya in 2011) to coercively extract the country’s oil and natural gas. This is an illegal act of aggression fit for King Leopold II of Belgium, not a U.S. president.

For more on my final analysis on this campaign, read here.

Understanding Atrocities: A Conversation with Dara Kay Cohen

I spoke with Dara Kay Cohen, assistant professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School, about her book, Rape During Civil War. To better understand this underexamined wartime atrocity, Dara built an original dataset and conducted extensive interviews in Sierra Leone, Timor-Leste, and El Salvador, including with perpetrators and victims. We discuss Dara’s research and her counterintuitive findings, which indicate that rape is often used as a tactic by some groups in civil wars to bond militants. We also talk about the role of academic research in informing policy, and Dara gives advice to young scholars considering a career in academia. A fascinating conversation with a thoughtful and brilliant scholar.

Online Store

Online Store