Whither the dollar-riyal-renminbi?

More on:

The funny thing about the dollar is that it is now kind of weak -- except against the currencies of those places that actually have large current account surpluses.

The dollar is close to record lows against many European currencies, and at multi-year lows against the Canadian dollar and the Australian dollar.

But the yen is even weaker, and China and the Gulf still track the dollar. Between them, Japan, China and the GCC countries (or the oil exporters writ large, as North Africa and Russia peg to either the dollar or a euro/ dollar basket) account for a very large share of the world's current account surplus.

China did let the RMB rise by 1.5% against in q2 – but that is not anywhere near enough to make up for its large accumulated undervaluation, ongoing Chinese productivity gains and the dollar's slide v lot of other currencies. China has depreciated over the course of this year against its the currencies of its largest trading partner (the EU). No wonder China’s current account surplus is big and still growing.

A lot of press reports confuse appreciating against the dollar with a broad-based real appreciation. They aren't the same thing. Not when the dollar is sinking.

The Saudis didn’t even let the riyal rise. It fell along with the dollar. That certainly isn’t helping to offset the inflationary pressures associated with the Gulf’s growing desire to spend -- especially in conjunction with a set of policy decisions that will increase the share of the windfall that is invested at home and reduce the share of the windfall that is invested abroad.

Oil at $70 plus and a 1.35-1.36 dollars/euro have attracted a lot less attention the second time around, but the combination is a sure recipe for both a large Gulf surplus – and a lot of gulf inflation. The Gulf’s surplus is falling (imports are no doubt way up, though perhaps not up 40% y/y like Russia’s), but it is still big.

And then there is the yen. The MoF isn’t intervening in the market to hold the yen down. Low yen interest rates, Ms. Watanabe and I suspect more than a few hedge funds - Jesper Koll’s work on the yen carry trade convinced me that it is sizeable -- are more than sufficient. So far, the rise in Japan’s current account surplus has prompted bigger outflows and a weaker yen …

There has been a bit of talk about how Japanese housewives have bought yen when foreign investors have sold yen and sold when foreign investors were buying yen, stabilizing markets. But my read of the post March data (presented here by the Econocator) is that both Japanese day traders and the pros have been betting against the yen. Like Gillian Tett, I wouldn't bet that Japanese housewives always will act to stabilize markets.Not all those borrowed yen though are flowing to the US. This isn’t 1998. The yen is low v. the dollar, but it is record low against pretty much the rest of the g-10.

Japanese investors -- and a few hedge funds - can get more carry financing the US, Australian and New Zealand current account deficits than financing the US current account deficit.

And if they don’t want to finance a current account deficit at all, there is always the euro. The Eurozone’s surplus with eastern Europe and the UK – along with rapidly growing exports to the oil exporting economies – offset its growing deficit with Asia. And the euro no longer yields all that much less than the dollar.

The dollar had a bad week, even in the absence of any really bad data coming out of the US. Macro Man (twice), Barclays Capital (via the Econocator) and Bloomberg all have hinted that China might have decided to start the quarter by selling dollars. Macro Man on Friday:

In FX, meanwhile, the market (or, more specifically, central banks) have decided that they are buyers of EUR/USD at current levels no matter what. So after payrolls produced a run of stop losses down to 1.3568, Macro Man's best buddies the central banks have helped drive it up to a high of 1.3642.

A bit of central bank selling seems likely to have contributed to the dollar's recent weakness. But it seems to me that the dollar fundamentally has been on emerging market central bank life support for some time. There is a reason why central banks are able to move markets.

The dollar's yield differential against countries with better balance of payments fundamentals is shrinking – and, at least for now, the US isn't growing faster than the other major economies. And should US growth pick up due to an acceleration of domestic demand, well, the already large US current account deficit would get even larger. While the US current account deficit isn't as big as the Australian or New Zealand current account deficit (as a percent of GDP), the US trade deficit is actually bigger than either the Australian or New Zealand trade deficits -- and that matters for the long-term dynamics.

Even with the weak yen, the dollar is now lower than it was in 2004 against the other major currencies – at least according to the Fed’s index. And the dollar is starting to drift down against the emerging world – see the Fed’s “other trading partners” series.

Here, though, the dollar remains fairly strong. Emerging currencies haven’t recovered from the 1997 crisis, even though their economies have. Indeed, the recent dollar depreciation against a basket of emerging economy currencies has basically just offset the depreciation associated with the set of crises of 2002-2003.

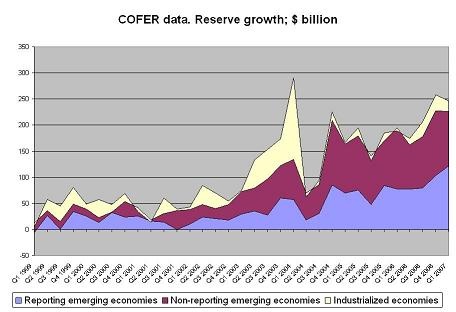

Bottom line: if you think the dollar is weak, just think how much weaker it would be if it was not attracting a record level of support from emerging economy central banks. Look at the COFER data through q1:

Using the COFER data to estimate dollar reserve growth -- and thus central bank financing of the US -- requires making a few assumptions about what countries that do not report are doing, but my best guess is that they are still buying a lot of dollars.

The COFER data only goes through q1, but I would be shocked if the data doesn’t show a further increase in emerging market financing in q2. The data from the 24 countries Christian Menegatti and I follow didn’t match the COFER data in q1 perfectly, but it generally matches up reasonably well – and it shows record intervention in April and May and then something of a fall-off in June.

Any estimate though for q2 is very preliminary though, as a lot of key countries -- notably China and many large oil exporters -- haven't provided data for May, let alone June. And I am still puzzled by the gap between the countries we follow and the COFER data in q1.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store