As part of China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the biggest infrastructure undertaking in the world, Beijing has launched the Digital Silk Road (DSR). Announced in 2015 with a loose mandate, the DSR has become a significant part of Beijing’s overall BRI strategy, under which China provides aid, political support, and other assistance to recipient states. DSR also provides support to Chinese exporters, including many well-known Chinese technology companies, such as Huawei. The DSR assistance goes toward improving recipients’ telecommunications networks, artificial intelligence capabilities, cloud computing, e-commerce and mobile payment systems, surveillance technology, smart cities, and other high-tech areas.

China has already signed agreements on DSR cooperation with, or provided DSR-related investment to, at least sixteen countries [PDF]. But the true number of agreements and investments is likely much larger, because many of these go unreported: memoranda of understanding (MOUs) do not necessarily show whether China and another country have embarked upon close cooperation in the digital sphere. Some estimates suggest that one-third of the countries participating in BRI—138 at this point—are cooperating on DSR projects. In Africa, for instance, China already provides more financing for information and communications technology than all multilateral agencies and leading democracies combined do across the continent.

People take selfies in front of Ethiopian satellite antenna during ceremony for the Ethiopian Remote Sensing Satellite, which was launched by China. Eduardo Soteras/AFP/Getty Images

People take selfies in front of Ethiopian satellite antenna during ceremony for the Ethiopian Remote Sensing Satellite, which was launched by China. Eduardo Soteras/AFP/Getty Images

Leaders of many developing countries, as well as some developed ones such as South Korea, have signed DSR agreements. Although these MOUs are not legally binding, they show the scope of global interest in the DSR. Countries in Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia desperately need inexpensive, high-quality technology to expand wireless phone networks and broadband internet coverage. Overall, the world’s infrastructure financing gap is projected to reach nearly $15 trillion by 2040. DSR-related investments can help fill that gap and spark growth by providing or helping finance this critical infrastructure. Chinese firms are bringing additional benefits to developing countries by establishing training centers and research and development programs to boost cooperation between scientists and engineers in these countries and their Chinese counterparts, and to transfer technical knowledge in areas such as smart cities, artificial intelligence and robotics, and clean energy, among others.

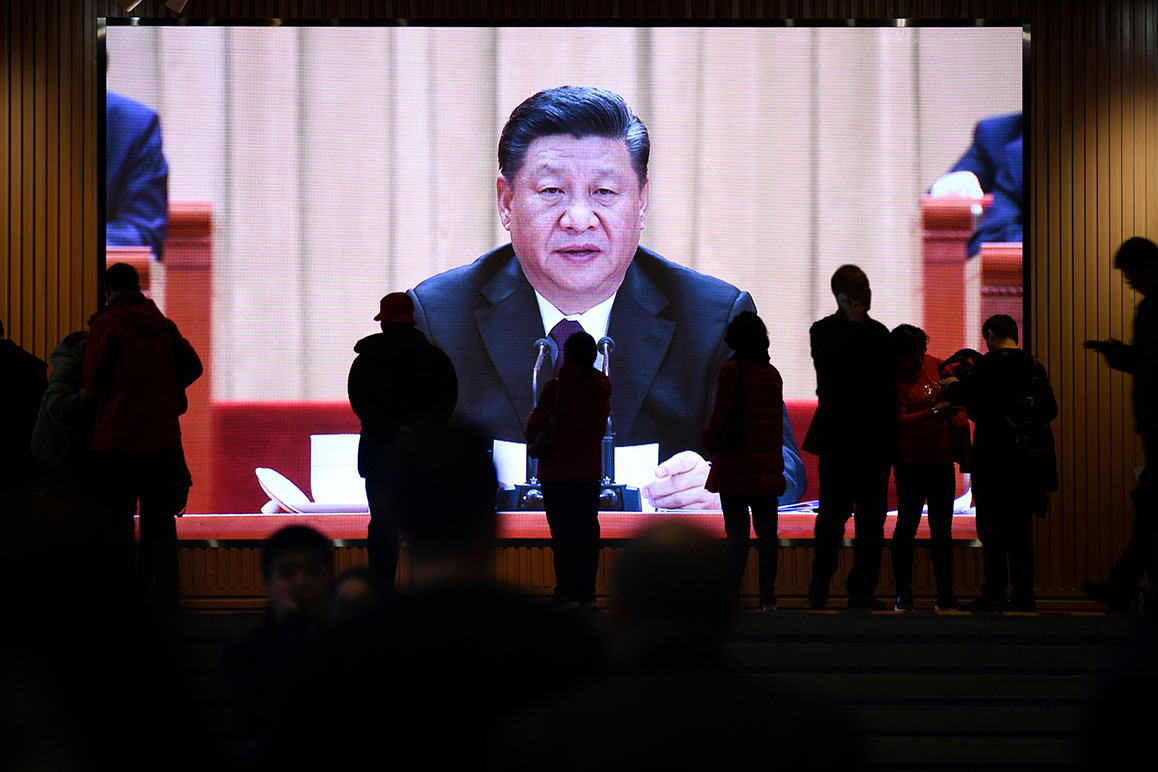

Still, some democracies have raised serious concerns about the Digital Silk Road. They worry that, at a time when Beijing is becoming more assertive on the global stage, China will use the DSR to enable recipient countries to adopt its model of technology-enabled authoritarianism, which would be detrimental to personal freedoms and sovereignty in those countries. Chinese technology companies have already helped governments in other countries develop surveillance capabilities that could be used against opposition groups, and Beijing has provided training for interested DSR recipient countries on how to monitor and censor the internet in real time. Although some of these Chinese companies are nominally private, even the private firms have drawn global scrutiny for state links as they are required by Chinese cybersecurity legislation to store data on servers in China and submit to checks from authorities.

Moreover, allowing Chinese firms to build countries’ fifth-generation (5G) networks and other infrastructure, and to set technology standards that could become the norm in many countries, could risk espionage and coercion of other states’ politics if Beijing used data breaches to blackmail political elites in those states. The DSR could also help recipient countries better control their internets through filtering, content moderation, data localization, and surveillance. Doing so would accelerate a fracturing of the global internet, as some countries pursue these policies of internet control while others remain committed to internet freedoms.

Click on the interactive map for a sample of countries with which China has signed DSR agreements and where it has launched DSR projects. Case studies of high-profile DSR investments show how China and recipient governments are using DSR and what the potential benefits and harms of their actions are.

The map below shows a sample of countries with which China has signed DSR agreements and where it has launched DSR projects. Click on the underlined countries in the list below to see case studies of high-profile DSR investments, and what the potential benefits and harms of their actions are.

Conclusion

The existing Digital Silk Road deals are just the start. Beijing is making the DSR a bigger foreign policy priority [PDF], as an increasing number of developed countries, including the United States, Australia, Japan, and some European states ban Chinese tech firms from their 5G infrastructure; launch broader strategies to limit Chinese tech giants’ expansion; and try to prevent Beijing from setting standards for the internet, 5G networking, and other areas. Chinese technology firms therefore need even greater growth in developing markets as they are excluded from wealthier states.

The coronavirus pandemic, which has led many governments to monitor their populations, has only added [PDF] to the demand in developing states for Chinese telecommunications and surveillance tools. In response, Beijing has linked the DSR to the Health Silk Road, a subset of the BRI that supports health infrastructure.

But as the DSR expands, concerns about its influence on recipient states will likely mount as well. Some developing countries, such as India, have expressed similar qualms as the United States and Europe have about China’s tech offensive. And policymakers in states such as Myanmar and Malaysia, another country involved in DSR projects, have expressed growing concerns over sovereignty and excessive debt. Beijing’s increasingly brittle and nationalist diplomacy is also undermining its efforts to assuage policymakers in developing states—even longtime close partners like Malaysia—about the potential downsides of DSR and BRI more generally.

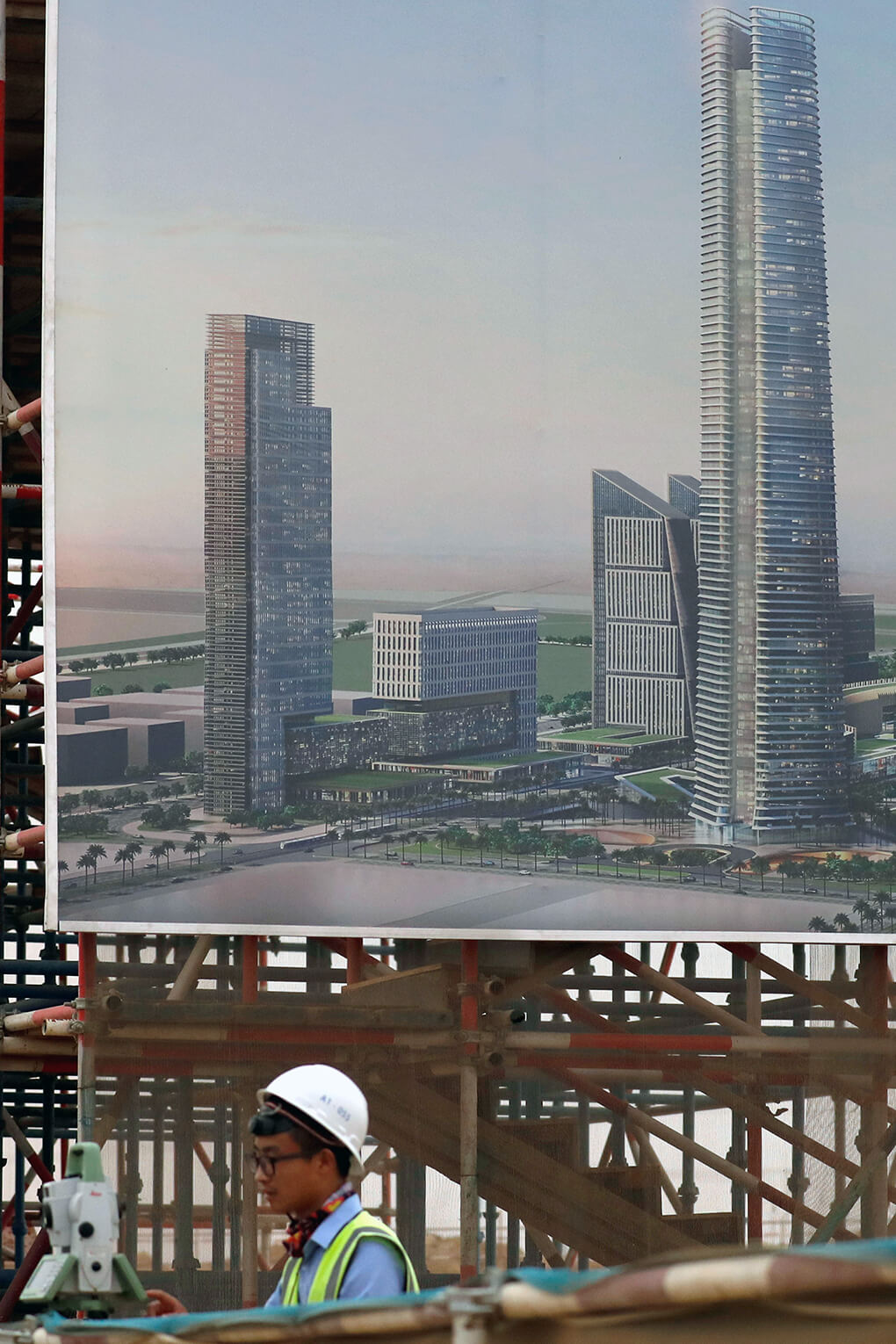

Buildings are pictured under construction in Egypt’s New Administrative Capital, in 2020. Chinese banks are financing the new capital. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

Buildings are pictured under construction in Egypt’s New Administrative Capital, in 2020. Chinese banks are financing the new capital. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

Chinese construction worker pauses in Lusaka, Zambia, in 2018. China is building and financing most of the digital infrastructure projects in Zambia. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

Chinese construction worker pauses in Lusaka, Zambia, in 2018. China is building and financing most of the digital infrastructure projects in Zambia. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

To be sure, China is not the only country whose major tech companies have participated in surveillance, cooperation with their countries’ militaries, and espionage abroad. Some U.S. tech giants have also used their networks to facilitate surveillance, espionage, and defense operations. U.S. companies such as Gatekeeper Systems also have sold facial recognition technology to authoritarian states such as Saudi Arabia. And, regardless of China’s actions, many governments have clear demands for surveillance and artificial intelligence infrastructure, as well as other technologies that raise serious concerns about privacy.

Despite concerns raised by developed states and some developing countries about aspects of DSR, Beijing will keep pushing forward. China has already spent an estimated $79 billion [PDF] on DSR-related projects, and its DSR assistance will likely grow substantially throughout the 2020s. At major China-sponsored international summits such as the World Internet Conference and the Belt and Road Forum, Beijing has promoted [PDF] DSR as a top Chinese priority.

As the Digital Silk Road expands, the conflicts around it—between countries signing up for DSR and those concerned about its downsides and between groups within countries worried about its detrimental effects and some governments that stand to benefit—will only intensify.

Methodology

The interactive map lists states known to be participating in the Digital Silk Road. The list of states was compiled from news reports, studies of DSR and Chinese digital assistance to other countries, and DSR signing agreements. It does not include every country to which China provides some digital aid, financing or investment, as many of these aid and investment deals remain opaque.

Resources

Robert Greene and Paul Triolo, “Will China Control the Global Internet via Its Digital Silk Road?,” SupChina, May 8, 2020.

Paul Triolo, Clarise Brown, Kevin Allison, and Kelsey Broderick, “The Digital Silk Road: Expanding China’s Digital Footprint,” Eurasia Group, April 29, 2020.

“Mapping China’s Tech Giants,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, November 2019.

Clayton Cheney, “China’s Digital Silk Road: Strategic Technological Competition and Exporting Political Illiberalism,” Net Politics (blog), September 26, 2019.

Thomas S. Eder, Rebecca Arcesati, and Jacob Mardell, “Networking the ‘Belt and Road’: The Future Is Digital,” Mercator Institute for China Studies, August 28, 2019.

Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca, “Belt and Road Tracker,” Council on Foreign Relations, last updated May 8, 2019.

“The Digital Side of the Belt and Road Initiative Is Growing,” Economist, February 6, 2020.

Acknowledgments

This interactive was made possible by the generous support of the Ford Foundation.

The author also thanks Elizabeth Economy, senior fellow for China studies; Julian Gewirtz, senior fellow for China studies; Shannon K. O’Neil, vice president, deputy director of studies, and Nelson and David Rockefeller senior fellow for Latin America studies; Adam Segal, Ira A. Lipman chair in emerging technologies and national security and director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy program; Sheila A. Smith, senior fellow for Japan studies; and research associates Lucy Best and Michael Collins for their comments on drafts of this interactive.

Joshua Kurlantzick, Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia

James West, Research Associate, David Rockefeller Studies Program

Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia

James West

Research Associate, David Rockefeller Studies Program

Patricia Lee Dorff, Editorial Director

Chloe Moffett, Associate Editor, Publishing

Sumit Poudyal, Associate Editor, Publishing

Katherine De Chant, Associate Editor, Publishing

Editorial Director

Chloe Moffett

Associate Editor, Publishing

Sumit Poudyal

Associate Editor, Publishing

Katherine De Chant

Associate Editor, Publishing

Doug Halsey, Chief Digital Officer

Lisa Ortiz, Director of Product and Design

Katherine Vidal, Deputy Director of Design

Donnie Bolen , Web Support Associate

Victoria Brooks, Senior UX | UI Designer

Will Merrow, Data Visualization Designer

Sabine Baumgartner, Photo Editor

Eric Spector, Deputy Director, Digital Development

Karen Mandel, Associate Director of Quality Assurance

Rob Osoria, Lead Developer

Aaron Potter, DevOps Engineer

Gabriel Gonzalez, Developer

Mariano Giagante, Quality Assurance Analyst

Doug Halsey

Chief Digital Officer

Lisa Ortiz

Director of Product and Design

Katherine Vidal

Deputy Director of Design

Donnie Bolen

Web Support Associate

Victoria Brooks

Senior UX | UI Designer

Will Merrow

Data Visualization Designer

Sabine Baumgartner

Photo Editor

Eric Spector

Deputy Director, Digital Development

Karen Mandel

Associate Director of Quality Assurance

Rob Osoria

Lead Developer

Aaron Potter

DevOps Engineer

Gabriel Gonzalez

Developer

Mariano Giagante

Quality Assurance Analyst