In Brief

Two Years of War in Ukraine: Are Sanctions Against Russia Making a Difference?

The United States and its allies have imposed broad economic penalties on Russia over its war in Ukraine. As the conflict continues, experts debate whether the sanctions are working.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the United States has implemented a broad sweep of sanctions focused on isolating Russia from the global financial system, reducing the profitability of its energy sector, and blunting its military edge. Ahead of the war’s second anniversary and after the death of jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny, Washington announced more than five hundred new sanctions targeting Moscow’s financial sector, oil and gas revenue, and military-industrial complex. These add to a bevy of sanctions that the United States imposed on Russia after it annexed the Ukrainian region of Crimea in 2014.

What sanctions has the United States imposed against Russia over the war in Ukraine?

The latest sanctions have targeted Russia’s:

More on:

Financial sector. The United States began its 2022 barrage of sanctions by freezing $5 billion of the Russian central bank’s U.S. assets, an unprecedented move to prevent Moscow from using its foreign reserves to prop up the Russian ruble. It also barred the largest Russian bank and several others from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), a Belgium-based interbank messaging service critical to processing international payments. Meanwhile, the U.S. Treasury Department prohibited U.S. investors from trading Russian securities, including debt; all together, the sanctions restrict dealings with 80 percent of Russian banking sector assets. Washington has also sought to seize the U.S. assets of sanctioned Russian individuals, including President Vladimir Putin.

Energy. The United States has also focused on reducing Russia’s ability to profit from the global sale of fossil fuels. The year before the war, Russia recorded more than $240 billion in energy exports, almost half of which came from oil. In March 2022, Washington banned the import of Russian crude oil, liquified natural gas, and coal, and restricted U.S. investments in most Russian energy companies. In December of that year, the United States and its Group of Seven (G7) allies implemented rules aimed at capping the price that other importing countries, such as China and India, would pay for Russian crude oil. So far, the United States has refrained from sanctioning Russia’s nuclear energy sector, and it continues to import Russian uranium. Russia supplied 12 percent of U.S. uranium imports in 2022.

Military tech. The U.S. Commerce Department has implemented restrictions that curb exports of high-tech products such as aircraft equipment and semiconductors to Russia with the aim of curtailing its military capabilities. The export restrictions extend to goods other countries produce using American technology.

Other. In January 2024, the United States and G7 imposed sanctions on Russian diamonds, one of the largest unsanctioned Russian exports at the time. Moscow recorded almost $4 billion in diamond revenue in 2022, with G7 countries accounting for about 70 percent of sales. The United States also sanctioned companies around the world, including in China, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, that it says have helped Russia evade sanctions.

As a result of these penalties, firms must ultimately choose to do business with Russia or with the United States and its partners, which together represent more than half of the global economy, Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo said at a CFR event in February 2024.

More on:

What are other governments doing?

The United States has implemented these sanctions in tandem with the European Union (EU) and other partners. While the EU has placed its own sanctions on Russian banks and individuals, including Putin, the bloc’s sanctions on Russian energy have proven the most contentious.

At the time of the invasion, Europe was Russia’s largest energy export market. Moscow was supplying nearly 40 percent of the natural gas consumed by the EU and nearly one-third of the bloc’s crude oil. Given that dependence and opposition from Hungary and other members, the EU has not imposed bloc-wide restrictions on gas imports. However, in 2022, the EU announced an embargo on imports of most Russian crude oil and joined the G7 price cap; in early 2023, it imposed an additional ban on Russian refined oil products such as diesel and gasoline.

The EU and other governments have also imposed sanctions targeting Russia’s financial channels and military technology. Indeed, two-thirds of the more than $330 billion in frozen Russian central bank assets are located in the EU, mostly in Belgium; U.S. and European lawmakers are increasingly calling to use seized Russian central bank reserves to finance Ukraine’s recovery. In December 2022, the bloc agreed to ban exports of some military hardware to Russia and its boosters, such as Iran. Meanwhile, Taiwan, the world’s leading producer of semiconductors, said it would restrict exports of computing chips, which can be used in drones and other military equipment, to Russia.

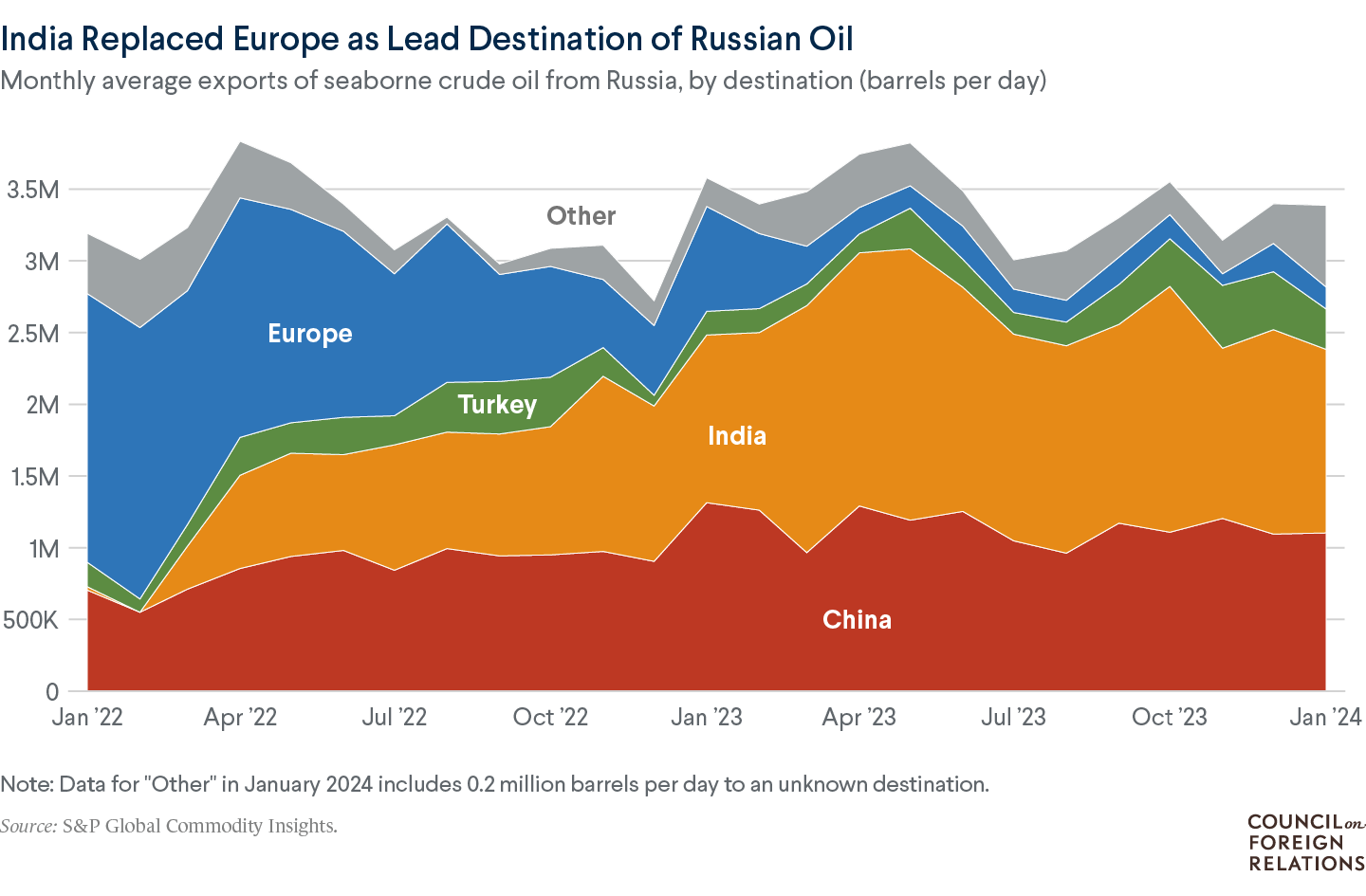

But some countries have taken little to no action against Russia or have otherwise seized on the moment to their own benefit. China and India, for instance, have increased their imports of Russian oil and natural gas. Others have acted as middlemen, importing Western goods and then sending them on to Russia.

Are they working?

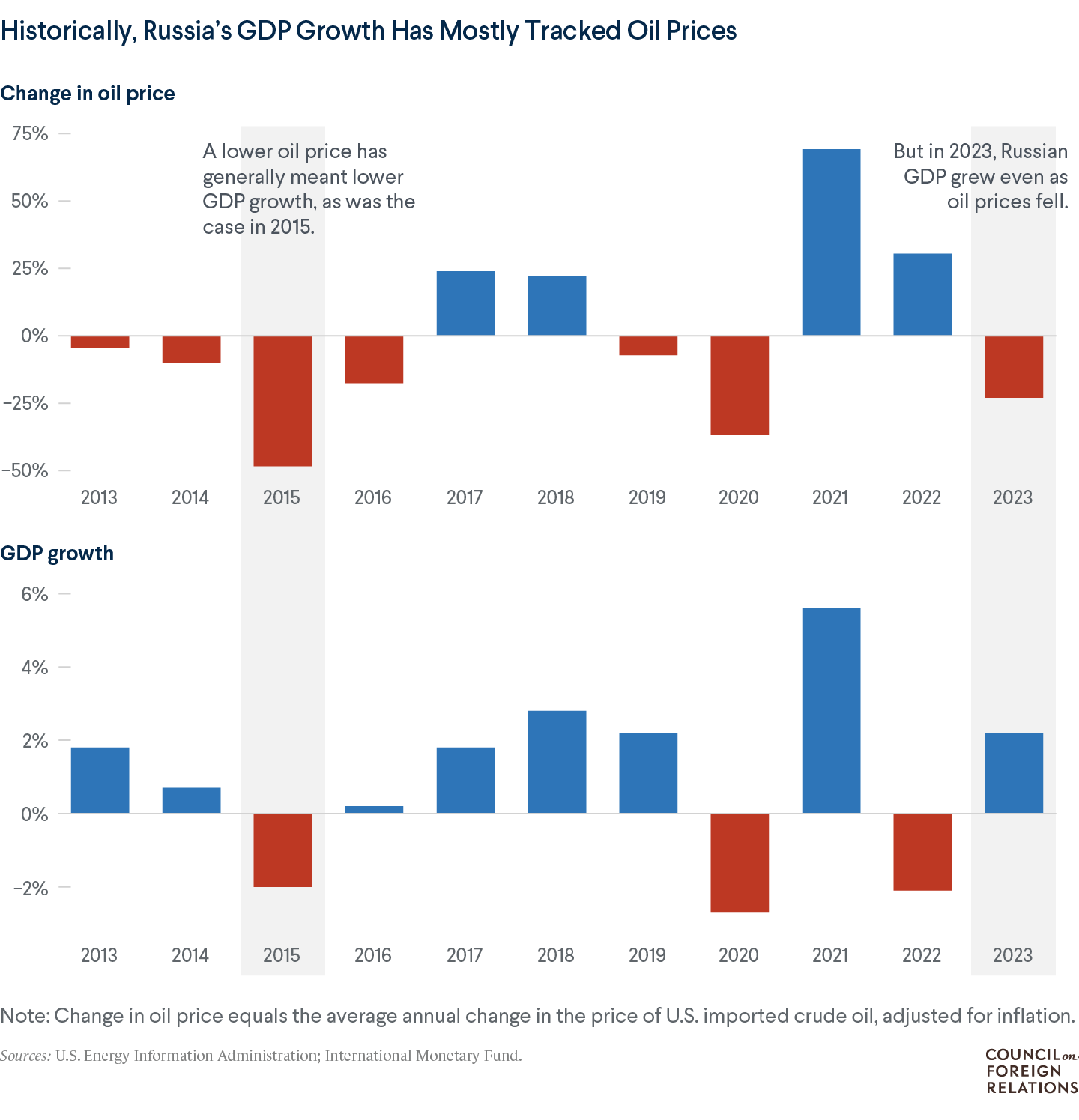

Sanctions have inflicted some pain on Russia’s economy, with oil and gas revenue declining in the months after the price cap was implemented and Russian central bank assets at risk of confiscation. But those sanctions have not caused widespread economic collapse or halted Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. In fact, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP) actually increased by 2.2 percent in 2023 thanks to massive war spending, a higher growth rate than the United States and many other Western economies.

Still, some sanctions supporters say the measures are not exclusively designed to crush Russia’s economy or end the war, but to send the message that violating international norms and invading a neighbor will be met with a strong coalition response. They point out that sanctions have still caused disruptions, noting shortages of critical goods such as medicine and airplane parts. Other proponents argue that the penalties will be increasingly effective over time, forcing Russia to make costly tradeoffs.

Analysts say Russia is a particularly difficult target given its export of many crucial commodities, including oil and gas, fertilizers, wheat, and precious metals. At times, Russia has wielded its status as an energy exporter to retaliate against Europe. In August 2022, Moscow shut down the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, which supplied almost 60 percent of Germany’s natural gas. It has also effectively adapted to the new sanctions regimes. Russia soon found ways around the G7 price cap, including by enlisting a “shadow fleet” of oil tankers and shifting exports to China and India. Meanwhile, many European countries continue to import Russian gas, which is more expensive than crude oil.

Prior to its 2022 invasion, Russia spent years building up more than $640 billion in central bank reserves, only half of which are now subject to Western sanctions. Moscow has also adjusted to conduct much of its bilateral trade in rubles and raised interest rates to stabilize its currency to roughly its pre-invasion level. Trade with China has grown significantly. In 2023, China imported record quantities of Russian energy, and 90 percent of trade between the two countries is now conducted in rubles and Chinese yuan, according to Russian state media, compared to 25 percent before the invasion. Beijing has also stepped in to supply Moscow with semiconductors and other technologies that could have military uses.

Anshu Siripurapu contributed to this In Brief. Will Merrow created the graphics.

Online Store

Online Store