Venezuela’s Chavez Era

Hugo Chavez assumed Venezuela's presidency in 1999 on a populist platform. But critics say three terms under his "socialist revolution" have made the country increasingly resemble an authoritarian state. This timeline offers a visual account of Chavez's rise to power and the impact of his presidency.

Following decades of rocky leadership by dictators and military juntas, Romulo Betancourt is elected president in 1958. Known as the "Father of Venezuelan Democracy," Betancourt oversees the 1963 elections, which usher in the first democratic civilian-to-civilian transfer of power. For the next three decades, Venezuela rides the boom-and-bust cycle of global oil prices under civilian democratic rule. Elections are limited to competition between the two main political parties through an early 1960s pact known as "puntofijismo," and corruption within the government is endemic.

Influenced by the nineteenth-century Venezuelan revolutionary Simon Bolivar, military officer Hugo Chavez establishes the leftist Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200 within the army. The movement borrows from Bolivar's belief in a unified Latin America, but it also draws inspiration from the leftist Peruvian military junta of the 1970s. As a teacher at the Military Academy of Venezuela, Chavez gains a reputation for rousing lectures and pointed criticism of the Venezuelan government. He travels the country to recruit new members for his political movement.

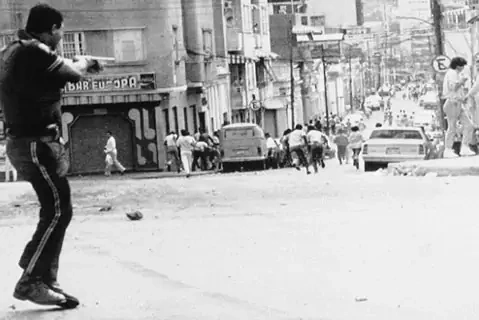

President Carlos Andres Perez implements free-market reforms, the so-called Washington Consensus, in an attempt to solve Venezuela's economic crisis. Later that month, Venezuelans riot against a massive increase in gas prices. Under presidential order, the country's security forces brutally put down the uprising. It becomes known as the Caracazo, or "Caracas smash." The government reports 275 deaths, but Venezuelan media sources claim at least three thousand people died. The riots and subsequent military crackdown have a polarizing effect on the general population as well as the military. As a result of the incident, the image of Venezuela as a harmonious, functional democratic state is shattered. Hugo Chavez begins attracting new recruits to his clandestine Bolivarian Revolutionary Movement-200.

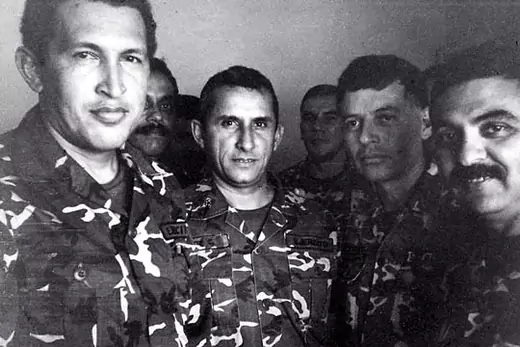

Hugo Chavez's Bolivarian Revolutionary Movement-200 attempts to overthrow President Carlos Andres Perez. Marred by blunders (the coup plotters are unable to capture Perez and a prerecorded tape urging civilians to rise up against Perez never makes it on the radio), the coup ends when Chavez surrenders to the government. He appears on national television to inform rebel detachments to cease fighting, and is subsequently imprisoned. The brief speech—in which he jokes that he has only failed "for now"—establishes a connection with viewers that makes him a political star. Former President Rafael Caldera says the coup attempt was a legitimate response to a corrupt system, comments which indicate that the puntofijismo system—an arrangement guaranteeing power to the two main political parties—could be in danger of collapse.

A group of air force planes allied with Chavez launches a second coup attempt, mounting attacks on the office complex of President Carlos Andres Perez. Armed forces loyal to the president foil the plot. Chavez is still in jail at the time, but records a video message of support from prison that is broadcast by rebels who overtake Venezolana de Television, a state-run station. The rebellion sparks rioting and attacks on police in slums surrounding the capital.

After his 1994 release from prison, Chavez runs for president. On the campaign trail, charismatic Chavez promises to end corruption, vanquish poverty, and scrap Venezuela's old political system—based on a pact that distributed power between the two main parties—to open up political power to independent political parties. Since 1990, Venezuela has endured five recessions, and the population is deeply dissatisfied with the widening gap between the rich and poor. Venezuelan media is largely sympathetic to Chavez's campaign. He wins the election with 56 percent—the largest percentage of the popular vote in four decades.

After taking office in February, Chavez launches Plan Bolivar 2000, an antipoverty program that includes road building, housing construction, and mass vaccination. In December, voters approve a new constitution that increases the presidential term to six years, expands presidential powers, converts the two-house National Assembly into a one-house legislature, and outlaws government financing of political parties’ electoral campaigns. It is the first time in Venezuelan history that a constitution is approved by popular referendum. In 2000, Chavez gains reelection with some 60 percent of the vote.

Up to one million Venezuelans march in opposition to Chavez’s appointment of political allies to top posts in the state-owned oil company PDVSA, ultimately clashing with Chavez supporters in a brawl that leaves nineteen dead and hundreds wounded. In the midst of the violence, Chavez is overthrown by members of the military high command and replaced by rightist businessman Pedro Carmona, who dissolves Congress and suspends the constitution. Following broad condemnation by Latin American states, the United States, which had acknowledged the Carmona government, condemns the putsch. Two days later, the pro-Chavez Presidential Guard seizes the palace and reinstalls Chavez. U.S. National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice says, "We do hope that Chavez recognizes that the whole world is watching and that he takes advantage of this opportunity to right his own ship, which has been moving, frankly, in the wrong direction for quite a long time." There remain multiple accounts about why the Carmona regime was so brief, including disunity in the coup movement, Chavez's populist sway with the masses, and unease by the military over a rightist government.

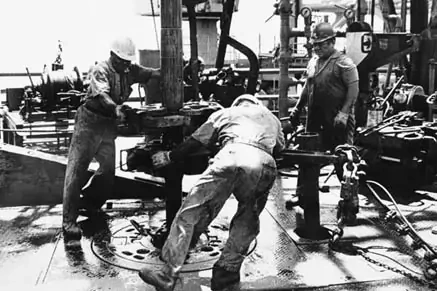

PDVSA goes on strike for two months in an attempt to force Chavez out of office. Chavez responds by firing the top management of PDVSA, as well as eighteen thousand employees, leveling charges of corruption and mismanagement. For the duration of the strike, Venezuela ceases exporting its usual 2.8 million barrels of oil per day, which causes a significant decline in gross domestic product in 2002 and 2003. Output resumes at some 2.3 million barrels per day, and many analysts say it still has yet to reach pre-strike levels, a claim the Venezuelan government disputes.

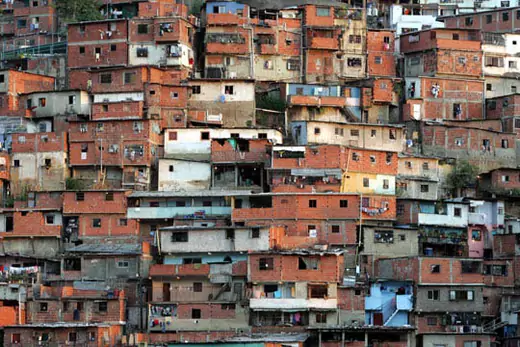

Chavez launches a series of wide-ranging social programs, the so-called Bolivarian Missions, to bolster public support. Run by various government bodies and ministries, the missions provide adult literacy programs, offer free community health care to impoverished communities, construct low-income housing for the poor, and subsidize food and other consumer goods. The public health clinics—many run by Cuban doctors—win praise from international organizations, including the World Health Organization and the United Nations. While some criticize the programs as inefficient and corrupt, the Venezuelan government reports significant increases in literacy and reductions in poverty levels.

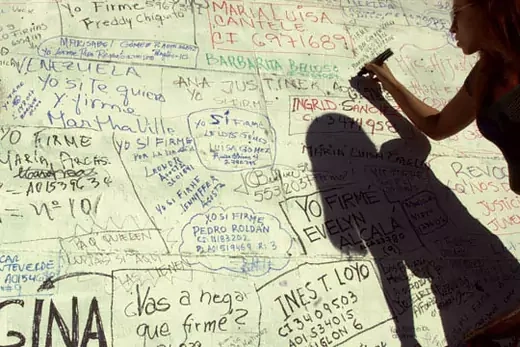

Growing dissatisfaction with Chavez's rule among some of the population enables opposition leaders to collect 2.7 million signatures on a petition requesting a presidential recall referendum. The petition leads the National Assembly to announce a recall vote. National Assembly member Luis Tascon publishes the list of names online as part of the procedure of verifying the signatures. The list's publication sparks allegations that Chavez supporters are discriminating against members of the opposition. Tascon later takes the list off the site. In August, a record number of Venezuelans—some 70 percent of the population—turn out to the polls, and the referendum is defeated with 59 percent of the vote. The Carter Center certifies the vote as fair, but numerous critics allege fraud.

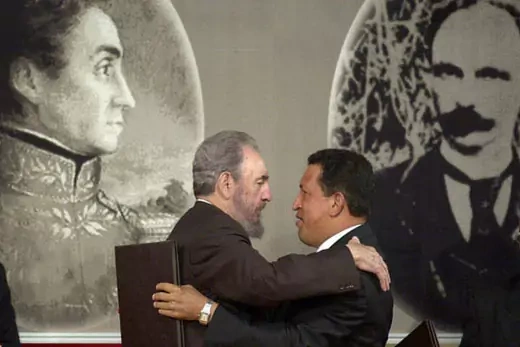

Chavez announces the creation of a two-million-person civilian military reserve to defend against foreign invasion. He also ends a thirty-five-year-old military relationship between the United States and Venezuela. Prior to Chavez’s election, U.S.-Venezuela relations had been close, marked by cooperation on trade and antinarcotics initiatives. Under Chavez's leadership, roughly half of Venezuela's oil exports still go to the United States. But tension between the two countries has increased due to Chavez's friendship with Cuban leader Fidel Castro and his vocal anti-American rhetoric. In December, the opposition boycotts the National Assembly elections, giving Chavez's allies control in the legislature. In 2006, Russia and Venezuela sign a $2.9 billion arms deal.

Chavez begins extensive travel abroad, strengthening relations with Iran, Russia, and China. Flush with funds from high oil prices, he makes generous deals to provide oil to neighbors in the Americas, including Bolivia, Nicaragua, Cuba, and the Caribbean. He also provides discounted heating oil to low-income communities in the northeastern United States. In 2006 he makes international headlines with his address to the UN General Assembly, in which he calls U.S. President George W. Bush the "devil." Chavez hopes to win a temporary seat on the UN Security Council, but following the fiery speech he fails to earn enough support during the October vote.

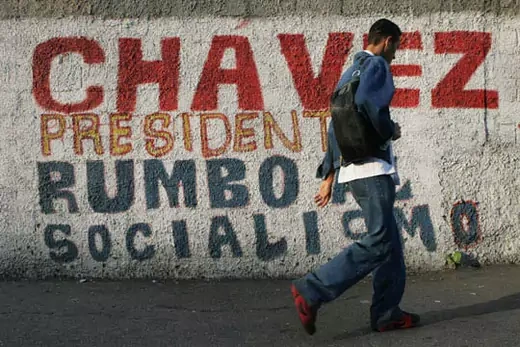

Chavez wins reelection with 63 percent of the vote, proclaiming: "Nothing can stop the revolution!" Shortly after his victory, he announces that he wants to create a single political party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). Chavez draws the bulk of his support from his own party, the Movement for a Fifth Republic. (The party seeks to establish the fifth era of politics in Venezuela since the country’s birth in 1811.) Roughly twenty other parties also support his presidency. In March 2007, the three largest coalitions express reluctance to join the PSUV, citing concerns over plurality of thought within the new unified party.

Chavez kicks off 2007 with a new mandate passed by the National Assembly—almost wholly controlled by chavistas. He replaces most of his cabinet, announces the nationalization of the telecom and electricity industries as well as the Central Bank, and cancels the broadcast license of private media company RCTV. He also proposes an act that gives him the power to rule by decree for eighteen months. In April, Chavez announces nationalization of oil projects in the Orinoco Belt, estimated by the state-owned oil company to have some 236 billion barrels of heavy crude, making it the largest petroleum reserve in the world.

Chavez withdraws from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank after paying off Venezuela's debts five years ahead of schedule. He then announces the creation of the Bank of the South to fund development projects in South America. One of the first proposed projects is an eight-thousand-mile oil pipeline that would pass through Brazil and Bolivia to connect Venezuela and Argentina. It's unclear how much funding Chavez will contribute to the bank. Though his public spending has doubled since 2004, inflation has risen substantially in Venezuela. The country’s budget deficit soared to $3.8 billion in 2006, leading some to question whether Chavez is running oil coffers dry.

Venezuela holds a referendum on sixty-nine amendments to the 1999 constitution. Among Chavez's proposals are controversial measures to abolish presidential term limits and to allow the president to suspend media rights and hold citizens without declaring charges during a state of emergency. In Chavez's first electoral loss in nine years, the referendum is defeated 51 to 49 percent. Despite speculation that he would not, Chavez concedes defeat and pledges to "continue in the battle to build socialism."

U.S.-Venezuelan relations reach a new low in the final months of the Bush administration after Chavez announces the expulsion of U.S. Ambassador to Venezuela Patrick Duddy and recalls the Venezuelan ambassador to Washington. Chavez purportedly takes this action as a show of solidarity with Bolivian President Evo Morales, who also expels the U.S. ambassador to his country, claiming the United States is organizing a coup against him. The U.S. State Department denies Morales' allegations, and shortly thereafter imposes new sanctions on three Venezuelan officials on grounds that they are involved in narco-terrorism. "When there's a new government in the United States, we'll send an ambassador," Chavez says. "A government that respects Latin America."

New York-based nongovernmental watchdog Human Rights Watch releases a 230-page report highly critical of the Chavez regime’s human rights record. The report says Chavez is manipulating the country's courts and intimidating the media, labor unions, and civil society. Human Rights Watch alleges that "discrimination on political grounds" and "open disregard for the principle of separation of powers" have been defining characteristics of Chavez's rule. In response to the report's release, Venezuela expels the director and deputy director of Human Rights Watch's Americas division, saying they had been "meddling illegally in the internal affairs" of the country.

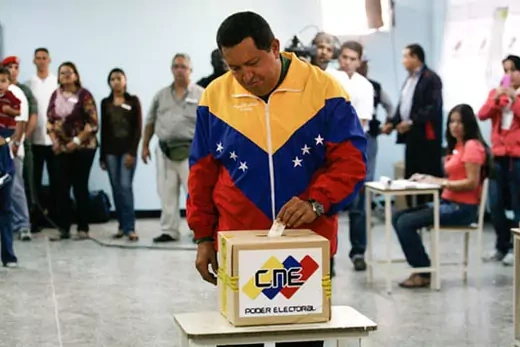

Venezuela holds a referendum on several measures, including a controversial amendment to abolish term limits for the president and several other official positions. Despite the failure of a similar referendum in December 2007, the amendment passes this time with 54 percent of the vote, officially ending the limit of two six-year terms mandated in the 1999 constitution. Upon learning of the victory, Chavez vows to remain in power for at least another decade to see through his socialist reforms. Opponents accept the results of the referendum, and say they will not contest them. Still, they say the poll is unfairly affected by Chavez's use of state resources to promote the referendum and mobilize voters.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) issues a report saying drug trafficking in Venezuela has increased, and cites widespread government corruption and the Chavez administration’s unwillingness to cooperate with U.S. counternarcotics efforts. The report says Venezuela has undermined the U.S. Plan Colombia counternarcotics program, pointing to a "permissive environment" in Venezuela for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a Colombian leftist paramilitary group funded in part by drug production and trafficking through Venezuelan territory. Chavez denies the GAO's allegations and accuses the U.S. government of hypocrisy, calling the United States "the top drug trafficking country on this entire planet."

Chavez announces that Russia has opened a $2.2 billion line of credit for Venezuelan arms purchases. Chavez plans to use the money to buy ninety-two T-72 tanks and an S-300 anti-aircraft rocket system. The announcement comes as tensions between Venezuela and neighboring Colombia reach a new high over Colombia's accusations that Chavez has been aiding the FARC, and because of a recent accord allowing the United States to use Colombian military bases in its counternarcotics efforts. Chavez says the anti-aircraft rockets are necessary to prevent an attack from the United States. "If that happens, they should know that we will soon have these systems installed, [and] for an enemy that appears on the horizon, there it goes," he says.

Venezuela's opposition coalition wins 65 seats out of 165 in the National Assembly election, breaking the two-thirds majority that President Hugo Chavez's Socialist Party of Venezuela held since 2005. Before the newly elected members take office, a pro-Chavez assembly allows him to rule by decree for eighteen months, during which he changes term limits, redistributes oil revenues, and redraws congressional districts. The redistricting ensures Chavez's party retains a majority, despite losing the popular vote to the opposition party. Chavez's popularity has slid in recent months, driven down by high crime rates, food shortages, and record-high inflation. Yet after results are posted, Chavez declares on his official Twitter account that the government has obtained a "solid victory, sufficient to continue deepening the democratic, Bolivarian socialism."

President Hugo Chavez has a tumor removed while in Cuba and disappears from the public eye for several weeks, prompting rumors about the seriousness of his undisclosed form of cancer. Despite several rounds of chemotherapy, Chavez announces a recurrence in February 2012. He is treated in Cuba with surgery and radiation, leading to speculation about how his health will affect the outcome of presidential elections scheduled for October 7, 2012, and his campaign against rival Henrique Capriles Radonski.

Henrique Capriles Radonski, the thirty-nine-year-old governor of the state of Miranda, wins the primary to represent the Coalition for Democratic Unity, a grouping of thirty opposition parties. In June 2012 he steps down as governor and registers as the candidate of the coalition in the October presidential election. Capriles, who promises a platform balancing social and pro-business programs, is an admirer of the policies of former Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. Capriles is considered a serious challenge to the ailing Chavez, who vows to accept the election results if he is defeated.

Chavez secures reelection for a fourth term, defeating Henrique Capriles' Democratic Unity Roundtable opposition coalition with 81 percent voter turnout. Venezuela's economic future and domestic security are top campaign issues, as the country struggles with frequent shortages of basic goods and a persistently high crime rate. The final vote is 54 percent for Chavez to Capriles' 44 percent—a smaller winning margin for Chavez than previous years, but a wider gap between the two candidates than most analysts expect. Chavez promises to keep the country on the path of Bolivarian socialism, and the opposition turns its focus to the December gubernatorial and mayoral elections. On October 11, Chavez selects foreign minister Nicolas Maduro as vice president as rumors continue to swirl about the state of the president's health.

Chavez announces in December 2012 that his cancer has returned. He undergoes surgery in Cuba, telling the public that should he become unable to serve as president, Vice President Nicolas Maduro should be the chavistas' pick. Chavez misses his January 2013 inauguration, sparking a nationwide debate over whether he is still legitimately president. The following weeks are beset with uncertainty as protesters demand clarity on Chavez's condition. Chavez returns to Caracas on February 18, announcing via Twitter that he will continue his treatment in Venezuela. Maduro announces on March 5 that Chavez has died. In thirty days new elections are to take place.

Following Chavez's death, a heated presidential campaign ensues between acting president Nicolas Maduro and opposition leader Henrique Capriles. Early polls show Chavez’s handpicked successor with a double-digit lead, but the April 14 election delivers a surprisingly narrow victory for Maduro with just 50.6 percent of the vote to Capriles's 49.1 percent.