- Experts

- Election 2024

-

Topics

FeaturedIntroduction Over the last several decades, governments have collectively pledged to slow global warming. But despite intensified diplomacy, the world is already facing the consequences of climate…

-

Regions

FeaturedIntroduction Throughout its decades of independence, Myanmar has struggled with military rule, civil war, poor governance, and widespread poverty. A military coup in February 2021 dashed hopes for…

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

FeaturedDuring the 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised that his administration would make a “historic effort” to reduce long-running racial inequities in health. Tobacco use—the leading cause of p…

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Public Health Threats and Pandemics

More people traveled internationally in 2019 than in any year in history. After COVID spread rapidly throughout the world, though, international travel plummeted, and nations across the world hardene…Book by Edward Alden and Laurie Trautman January 7, 2025

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

FeaturedDr. Mandy K. Cohen reflects on her time as CDC director, highlighting the progress and accomplishments of the Biden administration both domestically and globally.

Event with Mandy K. Cohen and Harold Varmus November 25, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Leaders Facing Justice

Since 1945, many regime leaders and key figures have been brought before domestic and international courts to answer to charges including genocide and crimes against humanity, amid a larger struggle to promote and enforce the rule of law worldwide.

Nuremberg Trials on the Holocaust

In the midst of World War II, the Allies issue a joint declaration in 1942 that notes the mass execution of Jews occurring under the German Nazi regime and calls for the perpetrators to face punishment. Three years later, the Nuremberg Trials, the first international war crimes trials, try to bring surviving leaders of the Nazi regime and engineers of the Holocaust to justice. The trials last four years, beginning with the Major War Figures Case, which comes before the International Military Tribunal established by the Allied forces. Eleven of the twenty-four defendants are sentenced to death. The United States conducts twelve additional trials that result in sixty-five convictions and more than twenty death sentences.

Postwar Trial of Japanese General

A U.S. military commission in Manila tries Japanese General Yamashita Tomoyuki for war crimes committed against prisoners of war and civilians in the Philippines in 1945. The commission convicts Yamashita on command responsibility grounds, which the U.S. Supreme Court upholds despite strong dissent from two justices, and he is sentenced to death. Yamashita is executed in 1946.

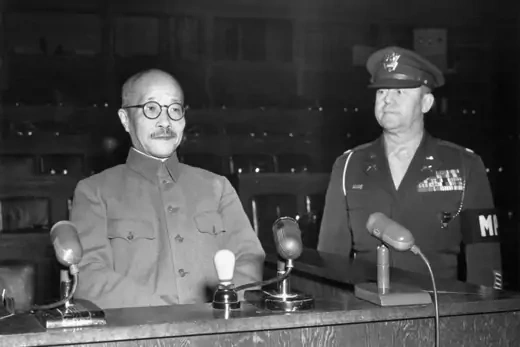

Tokyo War Crimes Trials

Under the watch of U.S. Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur, the International Military Tribunal of the Far East prosecutes twenty-eight high-ranking Japanese leaders for war crimes committed during World War II, including the killing and inhumane treatment of prisoners of war and civilian internees, as well as the destruction and mass murder of civilian populations in other countries. The most famous case is the conviction and execution of former Prime Minister Tojo Hideki. All of the defendants are found guilty, with sentences ranging from seven years in prison to execution. The Yokohama War Crimes Trials, for defendants charged with B- and C-class crimes, are held in the aftermath of the Tokyo trials before a U.S. military commission.

Argentina’s Trial of the Juntas

The Argentine government initiates trials for members of the military that ruled during the so-called Dirty War (1976–1983), for mass kidnappings and killings of left-wing activists, political opponents, and sympathizers. The Trial of the Juntas is the first in Latin America to bring former dictators to justice by a civilian, democratic government. In December 1985, several former military officials are convicted for crimes against humanity, with a life sentence for former de facto President General Jorge Videla. However, the next two presidents grant immunity to the remaining officers charged and pardon all those previously convicted. In 2003, President Nestor Kirchner replaces several members of Argentina’s Supreme Court, which overturns the amnesty law in 2005 and pardons in 2007, prompting trials to restart. In June 2012, Videla is convicted for the kidnapping of babies from political opponents and sentenced to fifty years in prison. He dies in May 2013 while serving his sentence.

International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

A UN Security Council resolution establishes the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia to try those responsible for mass killings of Bosnian Muslims, Croats, and Kosovo Albanians, as well as for abuses against ethnic Serbs, in the Balkans beginning in 1991. The most famous defendant is former President Slobodan Milosevic, whose trial begins in 2002. Milosevic is the first former head of state to be tried for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide; however, he dies in a UN detention center in 2006 before his trial concludes. Between 1993 and 2019, the tribunal indicts 161 people, the majority of them ethnic Serbs, and sentences ninety. Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, the two Bosnian Serbs most responsible for the Srebrenica massacre—considered the worst human rights atrocity committed on European soil since World War II—are arrested in 2008 and 2011, respectively. In 2016, Karadzic is sentenced to forty years in prison, and the following year Mladic is handed a life sentence. Also in 2017, former Bosnian Croat General Slobodan Praljak fatally poisons himself in court upon hearing his guilty verdict.

Tribunal for Rwandan Genocide

The UN Security Council creates the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) to bring to justice those responsible for the 1994 genocide, in which an estimated eight hundred thousand people, many of them ethnic Tutsi, are massacred. Between 1995 and 2015, the ICTR completes ninety-three cases, nearly all against members of the Hutu ethnic majority and including that of former Prime Minister Jean Kambanda. Kambanda pleads guilty to six counts—including genocide—and is sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity. The tribunal formally closes at the end of 2015.

Legal Battles of Augusto Pinochet

Former Chilean President Augusto Pinochet is arrested in October 1998 while seeking medical treatment in London. The warrant is issued by Spain’s National Court on the basis that it had jurisdiction over crimes against humanity committed by dictatorships in Chile and Argentina. The court’s ruling sets off an international dispute over where and how Pinochet should be tried, and after a yearlong legal battle, British officials rule he should not be extradited to Spain. Pinochet returns to Chile in 2000 and is subsequently indicted on a number of charges involving the forced disappearances and murders of political opponents. In the following years, he faces scrutiny over his mental capacity to stand trial and battles over his status of immunity from prosecution. In 2004, he is placed under house arrest in connection with nine kidnappings. Pinochet dies of congestive heart failure in December 2006 without being convicted for any of his alleged crimes.

East Timor’s Unfinished Trial

The UN Security Council authorizes a tribunal to investigate and prosecute grave offenses that occurred during the conflict that erupted over Indonesia’s annexation of East Timor in 1975. Fifty-five trials are held against nearly ninety individuals, eighty-four of whom are convicted. Many of those accused of crimes are Indonesian nationals and they are never tried because their government refuses to turn them over. Funding for the East Timor Tribunal and its investigative unit eventually runs out, leading to a backlog of more than five hundred unpursued cases.

Creation of the International Criminal Court

The Rome Statute, an international treaty signed by 139 nations, enters into force in July after being ratified by more than sixty countries, forming the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC, based in The Hague, Netherlands, is the first international permanent tribunal for the gravest violations of international law, including war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity. Countries that do not join include China, India, and the United States—which signed the Rome Statute in 2000.

Sierra Leone and the Charles Taylor Precedent

The government of Sierra Leone and the United Nations agree to establish the Special Court for Sierra Leone to try those most responsible for crimes against humanity committed during the country’s civil war. Between 2002 and 2012, twenty-one people are indicted for war crimes, including murder, rape, enslavement, extermination, and attacks against UN peacekeepers. The most famous defendant is former Liberian President Charles Taylor, who is turned over to the court in 2006 on charges that he directed the rebel forces that committed many of the atrocities in Sierra Leone. The court finds Taylor guilty of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and serious violations of international humanitarian law, making him the first former head of state to be convicted by an international tribunal since World War II. In May 2012, the court sentences Taylor to fifty years in prison.

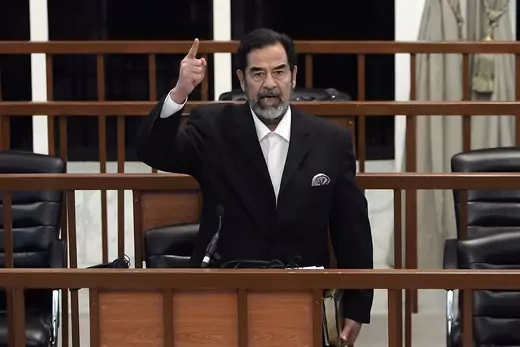

Iraqi Special Tribunal Convicts Saddam

The special tribunal is established by the U.S.-appointed Iraqi Governing Council in December 2003 to try Iraqis who committed human rights atrocities during former dictator Saddam Hussein’s rule, from 1968 to 2003. The interim government integrates the tribunal into the domestic legal system in 2005 and renames it the Iraqi High Tribunal. Saddam is accused of ordering the 1982 execution of about 150 Shiite Iraqis in the northern town of Dujail, killing some five thousand Kurds with chemical gas in Halabja in 1988, and invading Kuwait in 1990. The tribunal convicts Saddam in 2006, and in December he is executed by hanging. Several members of Saddam’s Baathist cabinet stand trial and are convicted over the next several years; they are eventually executed or sentenced to life imprisonment.

Cambodian Genocide Tribunal

In 2003, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) is established under Cambodian law. This follows a treaty between the Cambodian government and the United Nations to try senior members of the Khmer Rouge party and others most responsible for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide of Cambodians during the party’s rule in the late 1970s. Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot, who dies while being held under house arrest by a faction of his own party in 1998, is never brought to trial or convicted for authorizing the crimes. The ECCC goes on to try surviving party leaders. Three of the most senior leaders—Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan, and Ieng Sary—go on trial in late 2011. Sary dies in 2013 while the trial is ongoing. In 2014, Chea and Samphan receive life sentences for crimes against humanity and, in 2018, additional life sentences for genocide. Chea dies in 2019 while he appeals his genocide conviction. Khmer Rouge prison chief Kain Guek Eav, who managed the infamous S-21 torture center, is sentenced to life imprisonment in March 2012 for war crimes and crimes against humanity. At least two defendants await rulings as of 2021.

Peru’s Fujimori Tried for Shining Path Crackdown

In 2000, after ten years in office, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori faxes in his resignation from Japan amid a corruption scandal involving his intelligence chief, Vladimiro Montesinos. Fujimori is arrested in Chile in 2005, and two years later extradited to Peru, where he undergoes several trials for corruption and human rights violations allegedly committed during his presidency. In 2009, he is convicted and sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for authorizing two military operations that resulted in kidnappings and several civilian deaths, which Fujimori said were targeted at members of the Shining Path terrorist group. In 2017, President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski grants Fujimori a humanitarian pardon, a move later reversed by the country’s Supreme Court. In 2021, Fujimori is brought to trial again in a Lima court for his alleged role in the forced sterilizations of indigenous women.

Controversial Case of Congolese Rebel Leader

Former Congolese Vice President Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo is arrested outside of Brussels in 2008 on a warrant issued by the ICC. He is charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes committed by the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, forces under his command, in the Central African Republic from 2002 to 2003. In 2016, Bemba is convicted for crimes including sexual violence—the first such conviction by the ICC—and sentenced to eighteen years in prison. Two years later, however, Bemba is acquitted of all charges. The ICC Appeals Chamber rejects the conviction on the grounds of command responsibility, ruling that Bemba cannot be held responsible for crimes committed by his fighters. He returns to the Democratic Republic of Congo and announces his candidacy for president in the 2018 election, but is barred from running by the national electoral commission.

Sudan’s Bashir Wanted by ICC

In March 2009, the ICC indicts Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir for orchestrating a campaign of mass violence—including murder, torture, and rape—against non-Arab ethnic groups in the Darfur region since 2003. He is the first sitting president of a nation to be indicted by the ICC. Sudan, which is not a party to the Rome Statute and does not recognize the court, does not turn him over. The African Union (AU) also rejects the warrant, arguing that the ICC has a bias against African nations, and calls on member states not to arrest Bashir if he is received in their countries. In April 2019, following months of popular protests, the Sudanese military forces Bashir to step down and arrests him, though it says it will not hand him over to the ICC. Later that year, a Sudanese court convicts Bashir of corruption and financial crimes and sentences him to two years in detention. In 2021, Sudan signs an agreement with the ICC to move forward in the cases against Bashir and others, raising the possibility of Bashir's custody being transferred to the ICC.

The Case Against Qaddafi

In June 2011, the ICC indicts Libyan leader Muammar al-Qaddafi, his son, and brother-in-law for crimes against humanity arising from their authorization of the killing of protesters during Libya’s popular uprising. Qaddafi is killed by opposition forces in October, and one month later, his son, Saif al-Islam Qaddafi, is arrested during an attempted escape. In the following months, Libyan officials and the ICC dispute the location of Saif’s trial; Libyan authorities argue he should be tried in his home country, while the ICC maintains that he would have a fairer trial at The Hague. Qaddafi’s brother-in-law and intelligence chief, Abdullah Senussi, is captured in Mauritania in March 2012 and extradited to Libya, where, in 2015, he is sentenced to death. In 2019, supporters from Senussi’s Magerha tribe begin demanding his release, citing health concerns.

ICC Struggles to Prosecute Kenyan Crimes

Uhuru Kenyatta, Kenya’s finance minister and a deputy prime minister, is indicted in March 2011 on charges of crimes against humanity for his role in postelection violence in 2007 and 2008 that killed about 1,300 people and displaced hundreds of thousands. Kenyatta, a member of the Kikuyu ethnic group, is accused of helping plan and fund attacks against opposition-supporting ethnic groups in several southwestern cities; five other political figures are also charged. He and fellow defendant William Ruto, who runs on the same ticket, win the country’s 2013 presidential election despite the court’s ongoing investigation. In 2016, the court drops its cases against Kenyatta and Ruto, citing witness tampering and lack of cooperation.

Tunisian Leader’s Ouster in Arab Spring

Mass protests calling for the resignation of President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, in office for more than twenty years, erupt across Tunisia. After several weeks, the armed forces surround the presidential palace, and Ben Ali flees with his family to Saudi Arabia. The interim government calls on the international policing organization Interpol to issue an arrest warrant for him on charges of embezzling state funds. Saudi Arabia rejects extradition requests, and Ben Ali and his wife are tried in absentia and each sentenced to thirty-five years in prison. He is later convicted of other crimes, including possessing illegal drugs and weapons and ordering the killing of protesters. Ben Ali dies in exile in September 2019, without serving prison time.

Trial of Egypt’s Mubarak

Three months after resigning as president of Egypt, a post he held from 1981 to 2011, Hosni Mubarak is ordered to stand trial in a domestic court on charges of corruption and premeditated murder of Arab Spring protesters. The trial lasts from August 2011 to June 2012, when Mubarak is convicted of complicity in protesters’ deaths but is acquitted on corruption charges. The court sentences him to life in prison. Despite Mubarak’s verdict and sentencing, six senior security officials are acquitted of complicity in the killings, prompting nationwide protests. Mubarak is released from detention in 2017, and he dies in a Cairo hospital after undergoing surgery in February 2020.

Guatemala’s Genocide Trial

Former Guatemalan President Efrain Rios Montt is indicted in January 2012 for the killing of indigenous people during the country’s civil war, which lasted from 1960 to 1996. He is charged again in May 2012 for authorizing the 1982 massacre at Dos Erres, which killed more than two hundred people. In May 2013, a Guatemalan court finds the eighty-six-year-old Rios Montt guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity, making him the first former Latin American leader to be convicted on such charges, and he is sentenced to eighty years in prison. However, the constitutional court annuls the ruling days later, ordering the trial court to rehear the last month of the case. Rios Montt is retried in absentia but dies in 2018.

Special Tribunal for Atrocities in Chad

In 2005, Belgium issues an international arrest warrant for former Chadian leader Hissene Habre. Senegal, where Habre is living in exile, denies the extradition request. In 2012, the International Court of Justice rules that Senegal must try or extradite Habre, who is accused of ordering some forty thousand politically motivated killings and two hundred thousand cases of torture in Chad during the 1980s. The next year, the AU, Chad, and Senegal establish a special tribunal to try international crimes committed under Habre’s rule. The trial against Habre, the first by an AU-backed court of a former ruler for human rights abuses, begins in Senegal in 2015. That same year, a Chadian court finds twenty former state security agents guilty of committing torture under Habre’s leadership. In 2016, Habre, who denies any knowledge of the crimes, is convicted of rape, sexual slavery, and killings and sentenced to life in prison. He dies in prison in 2021 while being treated for COVID-19.

Former Ivory Coast Leader Charged With Crimes Against Humanity, Acquitted

Former Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo becomes the first former head of state to stand trial at the ICC, for crimes against humanity committed in 2010 and 2011. An estimated three thousand people were killed after Gbagbo refused to concede defeat in a national election and step down. Gbagbo is arrested in April 2011 amid French and UN military intervention and he faces four charges of crimes against humanity, including murder and rape. Gbagbo’s trial, initially scheduled for June 2012, is postponed after his defense team declares him ill from undergoing “cruel and inhumane treatment” in detention. The trial begins in 2016, and Gbagbo is acquitted and released in 2019, with the court citing insufficient evidence. In 2021, the ICC’s Appeals Chamber upholds the acquittal.

Kosovar President Steps Down After War Crimes Charges

In June 2020, a special court in The Hague indicts Kosovar President Hashim Thaci on ten counts of war crimes—including murder, forced disappearances, persecution, and torture—allegedly committed during the breakaway region’s conflict with the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1998–1999. Thaci, who pleads not guilty to the charges, headed the political wing of the rebel Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). The announcement of the indictment comes as Thaci (representing a now independent Kosovo) is traveling to Washington for U.S.-mediated reconciliation talks with Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, forcing him to abandon the White House meeting. He resigns in November and enters a Hague detention facility along with three Kosovar Albanian codefendants.

Online Store

Online Store