Assad’s Revelations

More on:

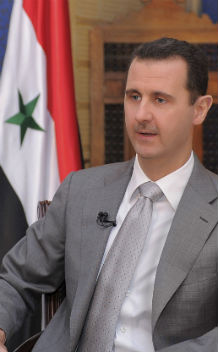

While President Bashar al-Assad’s circumlocutions were frustrating in his lengthy ABC interview last night, his exchange with Barbara Walters provided a window into the man and the way he deals with allegations of Syria’s misdeeds.

I twice had the opportunity--if that is the right word--to meet Bashar al-Assad in Damascus—once in 2003 when I accompanied then Secretary of State Powell to meet the Syrian leader, and a second time in 2004 when I was the White House member of an interagency team that went to present the dictator evidence of his misdeeds.

Then, the United States had five major sets of concerns about Syria’s behavior: its support for terrorist organizations, its brutal occupation of Lebanon, its facilitation of foreign fighters into Iraq to kill Americans, its opposition to peace, and its abysmal human rights record.

Both times I saw the Syrian leader in meetings, he demonstrated the same approach he employed last night. First, he displayed uncanny patience when confronted with allegations of his regime’s utter brutality. Most people would push back strongly to charges of murder, torture, and state-sponsored terrorism. But Assad’s responses were calm, deliberate, and mild, as if he had just been asked why he doesn’t pay his parking tickets.

In the interview, Assad demonstrated tactics I witnessed him use whenever he was asked about Syria’s objectionable actions—answering questions with questions, categorically denying basic facts, changing the subject, and demanding specifics rather than addressing larger charges:

Walters: The crackdown was without your permission?Assad: Would you mind, what do you mean by crackdown?

Walters: The, the reaction to the people, the some of the murders some of the things that happened?

Assad: No, there is a difference between having policy to crack down and between having some mistakes committed by some officials, there is a big difference. For example,when you talk about policy it’s like what happened in Guantanamo when you have policy of torture for example we don’t have such a policy to crack down or to torture people, you have mistakes committed by some people or we heard we have some allegations about mistakes, that is why we have a special committee to investigate what happened and then we can tell according to the evidences we have mistakes or not. But as a policy, no.

Or when asked about a United Nations report detailing Syrian brutality:

Walters: Last week an independent United Nations Commission who interviewed more than two hundred and twenty five people issued a report what it said was that your government committed crimes against humanity and they went on torture, rape and other forms of sexual violence against protesters including against children, what do you say to them, I mean what I am saying again and again is that protesters were, were beaten, things happened to them, um, do you acknowledge that, do you acknowledge what the U.N. said?Assad: Very simply I would say send us the documents and the concrete evidences that you have and we will see if that is true or not, you have not offered allegations now.

Walters: Did the U.N. not send you these documents?

Assad: Nothing at all.

Walters: You mean the first you’re hear--

Assad: They didn’t say. They don’t have even the names, who are the rape people or who are the tortured people who are they, we don’t have any names, they didn’t.

Walters: But they’ve issued--

Assad: Sorry.

Walters: Mr. President they have issued this report.

Assad: Yeah.

Walters: They have accused you and your regime...

Assad: According to what?

Walters: Well according to what they said is 225 people, witnesses, uh, men, women, children, whom they interviewed and identified and that’s when they called it crimes against humanity.

Assad: They should send us the documents, as long as we don’t see the documents and the evidences we cannot say yes that’s normal, we cannot say just because the United Nations who said that the United Nations is a credible institution first of all.

Walters: Who says if the United N--

Assad: Who said? We, we, we know that you have the double standard in the world in the United States policy in the United Nations that is controlled by the United States and this so it has no credibility so it’s about evidences and documents, whenever they have we can discuss it just to discuss the report that we don’t see in reality related to it. It is just a waste of time.

Or when asked about military defections:

Walters: Even some of your armed forces are not remaining loyal. Some of them have defected and some of them are fighting now against you, what do you say to that?Assad: What do you mean by defected?

Walters: Well they are-- some of your armed forces have left the military.

Assad: But every year, in the normal situation you have thousands of soldiers that fled from the army. You have it normal when you have this situation you have a little bit more you have higher percentage and then you have some few officers that leave the army to be against you and this cannot say if you talk about deflection in the army different from having few people deflecting so we cannot generalize.

Walters: You don’t think that they are a great many, you think it’s just a few.

Assad: No, otherwise we have different situation. You are in Syria now you see most of the things are stable if you have defection in the army you cannot have stable country or stable major cities like Damascus, Aleppo and the majority of Syria is stable.

Thus, Assad asks for proof of an allegation. Then when presented with evidence, goes on to challenge the veracity of the information, rather than addressing the larger point.

But despite his bobbing and weaving throughout last night’s interview, Assad did make some candid comments. First, he admitted that Syria was no democracy, conceding that the country did not have free elections, and that he was no elected official. Not news to anyone, but surprising candor nonetheless. Second, he conceded that the majority of Syrians are not active supporters, but then went on to blame the country’s ills on a minority of “terrorists.” Third, and most interestingly, Assad conceded that words don’t mean much to him anyway, at least if those words come from outside Syria:

Walters: Mr. President, you once had positive things to say about President Obama. Now President Obama says, and I quote, "President Assad has lost his legitimacy to rule, he should step down." What do you say to President Obama?Assad: I’m not a political commentator. I-- I comment more on action rather than word. At the same time if I want to care about something like this I would care, I would care about what the Syrian people wants. Nobody else outside Syria is part of our political map, so whatever they say we support, we don’t, he’s legitimate, or he’s not, it’s the same for me. For me what the Syrian people want, this is the popular legitimacy that put me in that position, and this is the only thought that can make me outside, so anyone could have his own opinion, whether president, official or any citizen, it is the same for me, outside our border.

Walters: Public opinion doesn’t matter?

Assad: Outside Syria?

Walters: Outside Syria.

Assad: No. It’s Syrian issue.

No, for Assad, actions speak louder than words. And the actions of the last few days have been telling: increased brutality in Homs, with dead bodies delivered to the city’s public square as a message to other would-be demonstrators; haggling with the Arab League over the entry of possible monitors into Syria which Assad would no doubt block and control anyway. The only actions that seem to matter to Assad are those of his army. He hinted that the only thing that would signify a challenge to him would be were the army to act:

Walters: You describe your country now as a stable country?Assad: In most of the areas, yes. We have trouble we have turbulence but not, not to the extent that you have a divided army. If you have divided army you are going to have real war. You don’t have war, you have-- instability is different from war.

Earlier today, NATO secretary general Anders Rasmussen publicly declared that NATO had no intention of intervening in Syria, the second time he has publicly assured Assad in recent months. Separately, U.S. officials announced a few days ago that U.S. ambassador Robert Ford was returning to Damascus to, in the words of State Department deputy spokesman Mark Toner, have a credible senior-level observer on the ground to “bear witness” to events unfolding there. For the period ahead, the path seems clear: Assad will continue killing and prevaricating while international powers seek to bear witness to the brutality of a dictator who thinks he is surviving. Are we sure he is not correct?

More on:

Online Store

Online Store