Case closed: A savings glut, not an investment drought

More on:

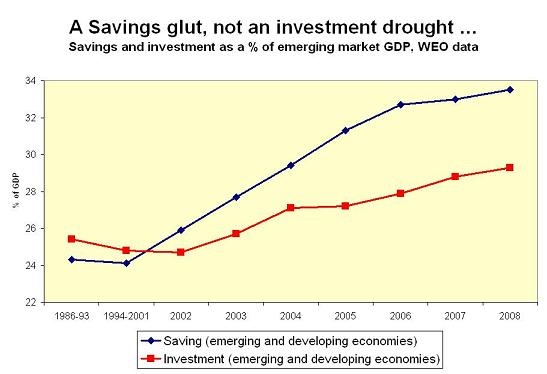

The data at the back of the IMF’s latest WEO (table A16) indicate that the emerging world’s savings surplus stems from a “glut” of savings, not a “drought” of investment.

In 2007, the savings rate of the emerging world savings was almost 10% of GDP higher than its 1986-2001 average. Investment was up as well – in 2007, it was about 4% higher than its 1986-2001 average. However the rise in the emerging world’s savings was so large that the emerging world could invest more “at home” and still have plenty left over to lend to the US and Europe. That meets my definition of a “glut.”

The big drivers of this trend. “Developing Asia” and the "Middle East." Developing Asia saved 45% of its GDP in 2007 -- up from 33-34% in 2002 and an average of 33% from 1994 to 2001 (and 29% from 86 to 93). Investment is up too. Developing Asia invested 38% of its GDP in 2007, v an average of between 32-33% from 1994 to 2001. Investment just didn’t rise as much as savings. The Middle East also saved 45% of its GDP in 2007 – up from 28% of GDP back in 2002 and an average of 25% from 1994 to 2001 and an average of 17-18% from 1986 to 1993. Investment is up just a bit -- at 25% of GDP in 2007 v an average of 22% from 1994 to 2001.

It is historically unusually for an oil importing region to be saving so much when the oil exporters are also saving so much. Usually a rise in the savings of the oil exporters is offset by a fall in the savings of the oil importers. The enormous rise in Chinese savings even as China’s oil import bill has soared (along with oil export revenues and oil exporters’ savings) implies a bigger fall in the savings of other oil importing economies.

Government policy has played a big role in the high savings rates in both regions – whether the undistributed profits of Chinese state firms (a policy choice) or large fiscal surpluses of the Gulf financed by the undistributed profits of the Gulf’s state oil companies. It isn’t an accident that the emerging world’s savings glut has coincided with a rise of state capitalism – and a surge in demand from states and state enterprises for “flying palaces.” I suspect the emerging world’s savings glut largely reflects a glut in government (and SOE) savings.

Dr. Delong has argued that this savings surplus will persist for a long time, keeping US and European rates low and keeping housing prices in both the US and Europe higher than otherwise would be the case. Krugman’s fear that home prices need to fall significantly to bring the price-to-rent ratio closer to its long-term average won’t be borne out.

Possibly.

However, I don’t think it entirely implausible that savings rates in both Asia and the Middle East might start to converge toward their long-term average. What goes up sometimes also comes down.

An end to the emerging world’s savings glut would not be such a bad thing either. It would mean than the young and poor were supporting global demand growth – not the old and rich. That makes more sense to me.

Update: some type-os were cleaned up after the initial post. PGL’s commentary on this post is also worth pondering, even if I am not fully convinced (see the comments).

More on:

Online Store

Online Store