Cyberspy vs. Cyberspy

More on:

Reuters had a special report on Chinese cyber espionage last week. It is very comprehensive, and definitely worth a read.

The report is built around a series of Wikileaks cables describing attacks on the State Department (codenamed "Byzantine Hades"), more commercially focused attacks on energy, technology, and financial firms, as well as on German military, research and development, and science interests. Unlike official public statements that are often vague about responsibility, the cables trace the attacks back to China, and to the People’s Liberation Army Chengdu Province First Technical Reconnaissance Bureau in particular.

The motivation for the attacks, and the topic of my testimony to the House Foreign Affairs Committee, is to raise China’s technological capabilities. I describe cyber espionage as part of a three-legged stool, where the other two legs are technology policy—top-down, state-led science and technology projects—and innovation strategy—bottom-up efforts to create an environment supportive of technological entrepreneurship. However, James Lewis’ quote sums it up well: "The easiest way to innovate is plagiarize."

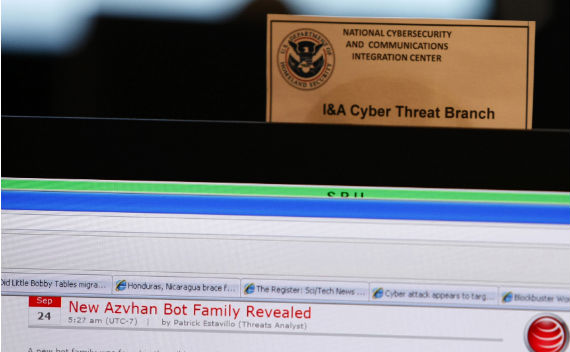

The public reporting of these attacks is likely to lead for more calls for information sharing, public-private partnership, and international collaboration. Certainly there is more to be done to improve these areas. Testimony last week to the House Homeland Security Committee described a case where law enforcement and intelligence agencies did not disclose an attack for 102 days. But there is a growing question of whether even the most technologically sophisticated companies can defend themselves from state-backed or state-supported hackers. Is more of the same going to be enough?

The Reuters report mentions a Track II discussion between China and the United States, and the FBI is sending a cybersecurity expert to cooperate with Chinese authorities on investigations. Because China’s leadership is broadly committed to the goals of reducing dependence on foreign technology though, any progress will be slow. The United States should continue to try and shape the debate within China, but the most important actions will be improving the defense of its computer networks and intellectual property.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store