The de facto nationalization of the global financial system

More on:

The US housing bubble. Bursting.

The “the triple bubbles in property prices, mortgage debt, and the shadow banking system.” Burst.

Soros’ thirty year super-bubble in leverage and financial assets. Bursting. Perhaps.

The bubble in Chinese stocks. No longer bursting. Who knows, China’s policy makers might even do enough to cause a bit of froth -- if not a bubble -- to reemerge.

Oil. Still going up. Maybe way up. And perhaps not a bubble. Perhaps the bubble that burst was the assumption that the supply of conventional (i.e. low-cost) oil was as elastic as it seemed to be in the 1990s. We still don’t know.

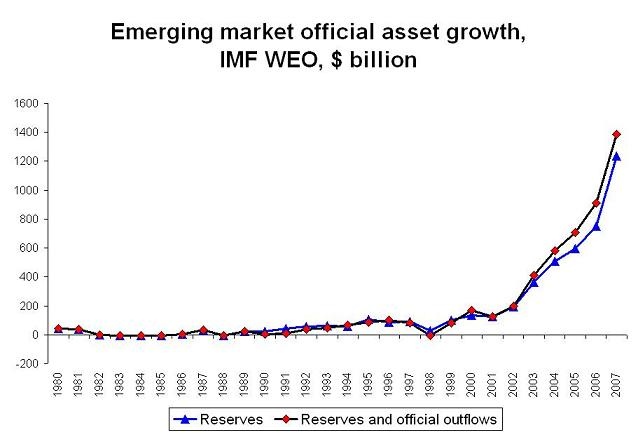

Emerging market government financing of the US and Europe? Still very bubblicious. Look at this chart, drawn from data presented in the statistical appendix of the IMF’s WEO.

The IMF data includes emerging market sovereign fund, the Saudis non-reserve foreign assets (which are counted as reserves) and valuation gains. It excludes China’s state banks and Asian NIE (Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan) reserve growth. Rather than do a ton of adjustments, I’ll just note that I believe that the increase in emerging market government assets that the IMF doesn’t pick up is about equal to the valuation gains that they include, so the overall picture isn’t that far off. The IMF data only covers the emerging world, so it also leaves out Japanese reserve growth and the increase in Norway’s sovereign fund. Together they amount to about $100 billion.

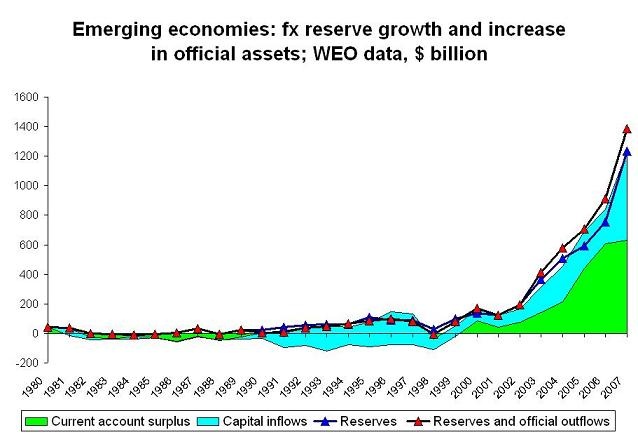

What is driving the strong growth? A dual surplus – a surplus in the current account and large net private capital inflows.

The following chart is also drawn from the IMF WEO data.

This isn’t just a product of high oil prices. In 1980, oil was quite high but emerging market official asset growth was about 0.5% of global GDP. It is now more like 2.5% of global GDP.

The main reason for the difference between the current era of high oil prices and 1980?

Asia, which imports oil, added to its official assets at an even faster pace than the oil exporting economies in 2007. That may not change in 2008, though the oil exporters are sure to give Asian oil importers a run for the title.

China’s foreign asset growth seems to have picked up to an absurd $200b a quarter pace. We still don’t really know, as China hasn’t indicated exactly how much foreign exchange was handed over to the CIC in the first quarter. And who knows what will happen in q2. China’s trade surplus usually builds over the course of the year, but rising oil may start to bite. But for all the uncertainty, China’s official asset growth will still be strong.

And if oil prices average $110b a barrel this quarter – and if the per barrel price needed to cover the oil-exporters import bill is about $50 a barrel – the external surplus of the oil exporters in the second quarter should be above $200b. If oil stays at its current level for the summer, that surplus will only get bigger. And most of that surplus goes to the state in one way or another. Some countries use their central bank. Russia’s reserves were up by over $25b in April alone, Saudi non-reserve foreign assets increased by around $40b in the first quarter; others use a sovereign fund.

Barring a major change, the Gulf and China could easily combine to add close to a trillion dollars to their official assets this year.

Nothing goes up forever. At some point, the pace of increase in official asset growth has to slow. But as of now, there isn’t much sign of a real slowdown.

Felix claimed not so long ago that the US was too big to fail. Certainly many emerging markets are doing their best to finance the US through its current troubles, and thus keep up demand for their oil and goods. But a part of me wonders if the rise in inflation in the Gulf and China and the difficulties both are facing trying to sterilize the rapid growth in the foreign assets is an indicator that there is a small risk that the US also might end up being a bit too large for the emerging world to save.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store