How much "capital flow reversal" insurance should the world offer?

More on:

That isn’t a question that is usually asked in the debate about the "right" size of the IMF. But it strikes me as a question worth asking.

Back in 2006, US growth slowed relative to growth in the world. Private demand for US assets fell.* But the US didn’t have to "adjust" -- that is to say bring its trade deficit down to reflect the reduced availability of private financing. Why not? Emerging economies, who received most of the influx of private money not going to the US, generally used this influx to build up their reserves. A rise in financing from central banks and sovereign funds offset the fall in (net) private demand for US assets.** The US trade deficit fell a bit relative to US GDP, but not by all that much.

Thanks to a generous supply of credit from the emerging world’s central banks, the party kept going long after private investors ceased to be willing to finance it.

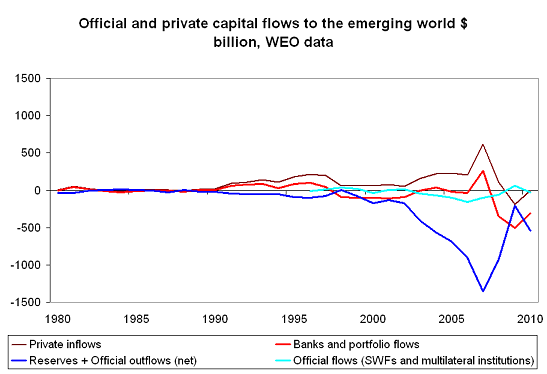

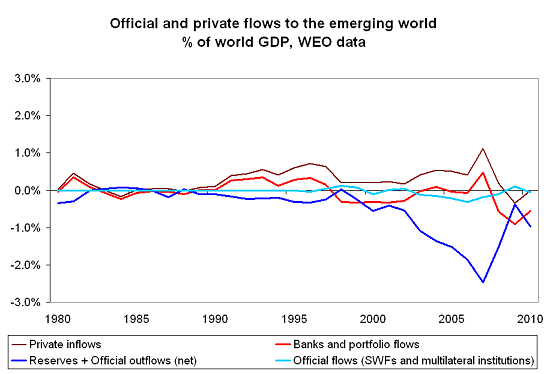

Suffice to say that when emerging economies running comparable deficits to the US encounter a comparable fall off in private financial flows, the amount of financing that gets recycled back their way by the US and EU (through institutions like the IMF) is far smaller. Between 1997 and 1999, "volatile" private capital flows (bank loans and portfolio flows, I left FDI out) swung from a $100 billion inflow to a $100 billion outflow. The net increase in IMF’s lending over this time by contrast was only around $30b -- not all that much relative to the $200 billion swing.

The current crisis isn’t all that different. Between 2007 and 2009, volatile capital flows are expected to fall from a positive $250 billion to a negative $400 billion -- a swing over over $650 billion. IMF lending -- based on all existing programs -- will increase by close to $120 billion (see this chart by my colleague Paul Swartz). That is more than in the past, but not enough to offset the fall in capital flows, and certainly not enough to offset the combined impact of lower capital flows and lower commodity prices on the commodity exporting region.

Scaled to world GDP, the current swing in private capital flows and the (projected) rise in official lending looks roughly similar to the swing back in 97-98.

I don’t know what the right balance between financing and adjustment is. No one probably does. And it clearly varies from country to country. Some countries are in worse shape than others.

But it is still striking that the emerging world did more to help the US avoid adjustment from say early 2006 to mid 2008 than the US, EU and Japan seem likely to do (through the IMF and World Bank as well as bilaterally) to help the emerging world avoid adjustment now, even with the recent expansion of the IMF.***

Call it part of the United States exorbitant privilege. So long as key emerging economies peg to the dollar and allow their reserves to rise when private demand for their financial assets rises, the US gets more protection from a sudden reversal in capital flows than other countries with large deficits.

But also call it part of a broad system that has resulted in a persistent uphill flow of capital -- and thus part of a broad system that led the US to run larger external deficits over the past few years than really were healthy.

* US investors started buying more non-American long-term assets while (private) foreign investors lost interest in US assets. The fall in private demand though wasn’t immediately apparent because a lot of official flows initially registered as private flows through the UK and other financial centers.

** $100 billion in "private" outflows from China in 2006 lowered the global total. Those private outflows though were clearly the product of an effort to hand some of China’s reserves over to the state banks to manage. They weren’t really private.

*** It also interesting that the $200 billion or so in financing Russia got from the sale of its reserves far exceeds the IMF’s total commitments to date; that helps put the IMF’s actions in context.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store