The IMF’s data for global reserve growth in q3

More on:

I would caution against reading too much into the fall in the dollar's share of global reserves in the latest IMF COFER data release for two reasons:

First, most of the fall in q3 is explained by the rise in the dollar value of the world's existing holdings of euros and pounds. The euro rose from around 1.35 to a bit over 1.42 in the third quarter. The rise in the dollar value of the world's existing holdings of euros from currency moves explains at least $50b of the overall increase in euro holdings.

Second, the diversification that is taking place is coming from the world's advanced economies, not the world's emerging economies. After stripping out valuation gains, the advanced economies added $10.7b euros to their stockpile -- a far larger sum than the $3.1 billion increase in their dollar holdings. Either Japan diversified at the margin or a host of European countries continued to shift away from dollars. Those emerging economies that report data to the IMF, by contrast, bought three times as many dollars ($61.4b) as euros ($21.2b).

If emerging economies that do not report detailed data on the currency composition of their reserves acted like other emerging economies, dollar reserve growth remained very strong -- though not quite as strong as in q1 or q2. Central bank financing of the US hasn't ended. (UPDATE: supporting data has been added below)

The reserves of reporting emerging economies rose by $132.7b, with a $61.4b increase in dollar reserves and a $53.8b headline increase in euro holdings. But valuation changes explain over $30b of the increase in euros. I have yet to break out the impact of valuation gains on the remaining $17b of the $132b overall increase -- but valuation changes undoubtedly were a factor there as well.

Consequently, to me the big story remains the ongoing increase in overall reserve holdings. Valuation gains explain a big chunk -- probably around $100b, but I need a bit more time to do the analysis (update: valuation changes look to have added more like $80b)-- of the $317b headline increase in q3. But around two thirds of the increase comes from ongoing intervention in the foreign exchange market. Valuation gains also explain a portion of the $1287.2b increase in global reserves over the last four quarters. But the core story remains the enormous -- indeed, unprecedented -- overall growth in global reserves and the enormous growth in central bank holdings of dollars.

A lot of that growth -- $146-147b in q3 comes from countries that do not report data to the IMF. On the assumption that countries that do not report hold about 1/3 of their reserves in euros and similar currencies and the remainder in dollars, valuation gains account for maybe $35b of the total increase. That leaves $110b in real growth (v around $90b from the emerging economies that do report).

If 75% of that increase was held in dollars and 25% in euros (a breakdown that resembles the breakdown from those countries that do report), countries that do not report added $83.4b to their dollar holdings. That would bring the global total up to around $150b in q3.

That is down from q1 and q2. But it isn't small.

And that total doesn't include the increase in the non-reserve foreign assets of the Saudi Monetary Authority, the CIC, other sovereign funds or the large increase in the dollar holdings of Chinese banks (remember, Chinese reserve growth was unusually low in q3).

More later!

UPDATE: Nothing like a lengthy weather-related delay to provide time for a bit of number crunching. Best that I can tell, funds shifted to the Chinese banks and Saudi non-reserve foreign assets added about $37b to the global total for q3 (The Saudi adjustment is straightforward, the Chinese adjustment hinges on the considated foreign exchange balance sheet of the Chinese banking system), bringing headline reserve growth up to around $354b in q3.

Valuation changes explain about $80b of the overall increase. Total valuation adjusted reserve growth was in the $275b range. The size of the euro's move in q3 though means that this estimate is depends more than usual on getting the estimated euro holdings of countries that do not report data to the IMF (notably China and Saudi Arabia right).

The total increase in dollar reserves is around $175b. That estimate assumes that emerging economies that do not report data to the IMF reduced the dollar share of their reserves by about 0.8% -- i.e. they acted more or less like the emerging economies that did report detailed data to the IMF. If the non-reporting emerging economies held their dollar share constant, the total increase in dollars could have been as high as $200b. That growth is why articles indicating that central banks "lost" appetite for dollars are misleading -- the quarterly increase in dollar holdings was only higher in five quarters: q1 2004, q4 2004, q4 2006, q1 2007 and q2 2007.

This estimate is subject to a large margin of error -- i estimate, using a data series that Christian Menegatti and I developed -- that after adjusting for valuation effects, industrial countries added $3b to their dollar portfolio and $16b to their non-dollar portfolio (i.e. they actively lowered the dollar share of their portfolio), that reporting emerging economies added $61b to their dollar portfolio and $38b to their non-dollar portfolio and emerging economies that do not report added $113b to their dollar portfolio and $44b to their non-dollar portfolios.

Christian and I have stress-tested our estimate of the currency composition of countries that do not report in a lot of different ways. It is reasonably robust -- at least so long as my estimates for the dollar share of China's portfolio are robust. But with so much of the estimated increase in dollar holdings coming from countries that do not report detailed data to the IMF, there is a higher than usual margin of error.

Taking a slightly longer perspective, over the last four quarters, the "headline" increase in global reserves -- counting reserves managed by Chinese state banks and the non-reserve assets of the Saudi Monetary Authority but not the growth of the assets managed by the Gulf sovereign wealth funds, Norway's government fund, Singapore's GIC and Temasek and the CIC -- over the last four quarters was $1394b. The valuation-adjusted increase was only $1212b, with an estimated $182b of the increase coming from valuation changes.

These are absolutely huge numbers. If they are right - and the main source of potential error would be a higher than estimated euro share in China and Saudi Arabia, and thus larger valuation gains -- total "official asset" growth, counting oil revenue transfered to sovereign wealth funds, is in the $1.3 trillion range. Trillion.

Dollar holdings are likely up by between $800 and $900b -- and inflows to the eurozone are likely in the $300-400b range. Those are also enormous sums.

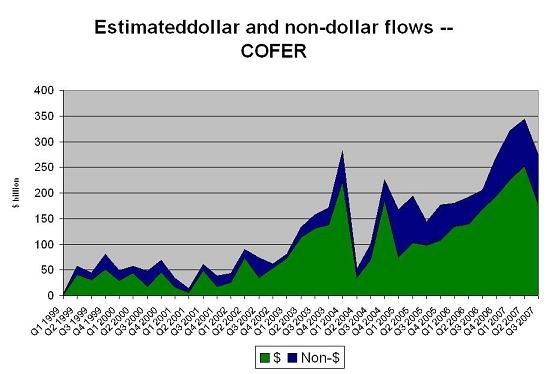

Words can only convey so much -- pictures often work better. The following chart shows quarterly valuation-adjusted global reserve growth, with dollar and non-dollar reserve growth broken out.

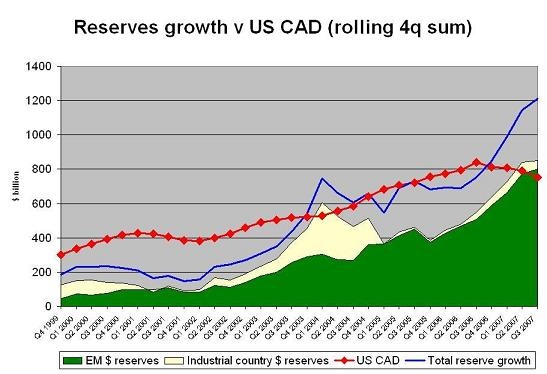

The next chart shows the rolling four quarter sum for total reserve growth, the US current account deficit and my estimate of dollar reserve growth.

It sure doesn't seem like dollar reserve growth has stopped to me -- on a rolling four quarter basis, it never has been higher.

One last point. If the world's central banks has done absolutely nothing other than hold on to their existing portfolio, the dollar's share of global reserves (among reporting countries) would have fallen by 0.9% (almost a full percentage point) simply from the rise in euro relative to the dollar. That explains the majority of the 1.2% overall fall in the dollar's share of global reserves. Valuation changes alone explain almost all of the fall in the dollar's share of those emerging economies that report -- the only real diversification came from industrial economies.

That is why I am not a fan of the current convention of looking at the dollar's share of reported reserves in the COFER data to assess whether the dollar is losing its status as a reserve currency.

Right now, the small fall in the dollar's global share -- a fall that is most likely due to a small shift in the portfolios of some European central banks along with moves in the euro/ dollar, not from a major shift in the activity of reporting emerging economies -- isn't the real story. The real story is the huge growth in central bank reserves, euros and dollars alike, over the past year.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store