The IMF’s forecast for the global current account

More on:

The IMF – as the FT, Stephen Roach and William Pesek have all noted -- has decided to stop worrying about what might go wrong in the global economy and start celebrating all that is going right.

Slower US growth doesn’t even imply slower global growth.

Not with China growing even more rapidly than in the past, helping commodity exporting emerging economies in the process.

Not with Europe doing well. Two years ago the conventional wisdom was either that Germany hadn’t reformed enough or that it had adopted the wrong kind of reforms, so it couldn’t grow. Now the conventional wisdom seems to be that it did enough to lay the basis for sustained growth …

Large and growing imbalances haven’t caused any problems to date. The markets aren’t worried. David Hale isn't worried. The G-7 isn’t worried. Academics generally aren’t worried.

Why then should the IMF worry?

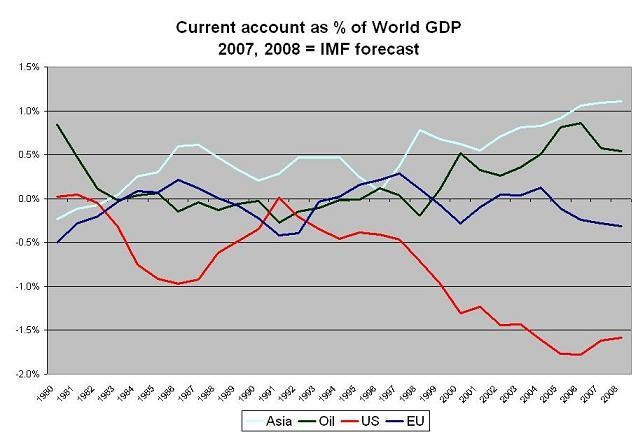

While the world's imbalances are large, they aren't expected to get bigger. Look at the following chart, which is based on the forecast in the IMF's World Economic Outlook.

Several things in this chart -- which shows the deficits and surpluses of several major parts of the world economy relative to world GDP -- jump out at me.

One is that the surplus in the world’s oil exporting economies (I summed up the surpluses of Africa, the Middle East, Russia and Central Asia, Norway and Venezuela) is now as large, relative to world GDP, as it was in 1980, after the second oil shock.

Another is that Asia’s surplus rose even in the face of the most recent surge in oil prices. Back in the 1980, Asia ran a deficit. Now its surplus is at record levels.

That is the unusual feature of today’s world economy – the oil exporters and one oil-importing region are running record surpluses simultaneously.

What does the IMF expect to happen in 2007 and 2008?

US growth will slow relative to world growth. That will lead the US external deficit to shrink slightly as a share of world GDP (it stays about the same size in nominal terms).

Asia’s surplus remains about the same.

The improvement in the US deficit is balanced by a fall in the surplus of the oil exporting economies, and by a rise in the EU’s deficit.

That is a plausible forecast. But I am not totally convinced.

Some the data from the first quarter doesn’t fit perfectly with the forecast.

But first, there is one point that I am pretty sure the IMF has right: barring a big surge in oil prices, the oil exporters’ surplus should fall. Import growth really picked up in the oil exporting economies in 2006, and that looks to continue in 2007. Stable oil prices and rising consumption = a smaller surplus.

Asia’s surplus, though, looks to be increasing – not stable. China’s surplus is certainly still growing. Japan’s surplus isn’t shrinking either. I don’t think the rest of Asia will be able to offset a $80-100b increase in China’s surplus. 30% export growth off a $1 trillion base puts up impressive numbers.

And what of Europe? Well, the eurozone isn’t the same as the EU. But the eurozone’s deficit shrank significantly in the fourth quarter of 2006. The rolling 12 month current account is now roughly in balance (chart here). There isn’t much data for q1. But judging from the q4 data, the eurozone’s deficit looks to be disappearing – not expanding.

The eurozone’s oil import bill certainly fell in q1 (oil fell more in euro terms than in dollar terms … ). And I suspect the eurozone is selling a lot of goods to the oil exporting economies.

That may offset rising European imports of Asian – and even American -- goods. At least for a while. Eric Chaney certainly seems concerned about the future impact of the Euro’s current strength.

Chaney gets to the nub of the issue. While dollar weakness makes some sense (look at the chart above), the weakness of Asian currencies doesn’t (again, look at the chart). It generally isn’t a market outcome either.

“For euro area policy makers, the catch is that they have already implicitly acknowledged that a weaker US dollar makes sense, in order to reduce the US current account deficit that they have identified as a threat for financial stability and, ultimately, global prosperity. However, since a weak US dollar implies a weak Japanese yen and a weak Chinese yuan, the euro and closely related currencies, such as the British pound or the Swiss franc, are getting excessively strong, by default. President Trichet noted with exquisite diplomacy that the “IMF should distinguish between market-driven exchange rates and policy-driven rates”. Not being constrained by diplomatic etiquette, I would express the same idea more directly: current exchange rates do not reflect economic fundamentals because of political actions interfering with market forces.”

If “decoupling” of US and European growth means not just a weaker dollar but a weaker yuan, decoupling may not lead to external rebalancing.

The world's current account surpluses and its deficits have to add up, as they offset each other. If Asia is set to run a larger surplus and Europe a smaller deficit than the IMF forecast, something else has to change. The oil surplus has to fall more than the IMF forecast – or the US deficit has to be bigger.

And that, to me, isn’t entirely implausible.

If the US shakes off the housing slump on the back of still solid consumer spending and US growth picks up toward the end of the year – as many expect – the US deficit may not shrink quite as much as the IMF assumes. Strong consumption growth suggest rising imports (and falling household savings). And there are some worrying signs that the pace of US export growth is slowing. Throw in a rising income deficit, and the US deficit might not fall.

The fall in the oil surplus may result in a further rise in Asia’s surplus – not a fall in the US deficit. That at least is my worry.

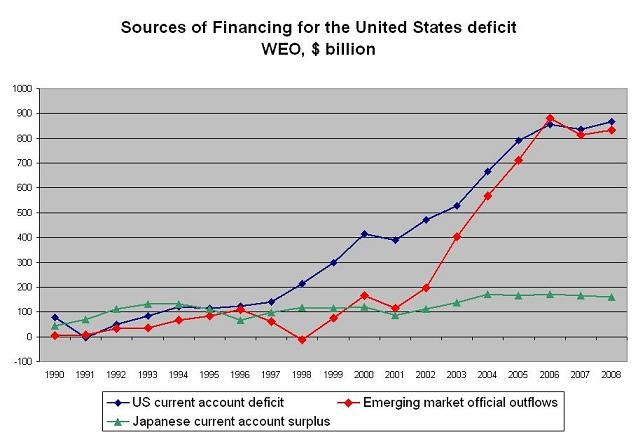

And who will finance that deficit? The IMF’s data doesn’t leave much doubt there. Central banks and oil funds (probably more central banks and less oil funds). The following chart really doesn’t need any words.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store