More on:

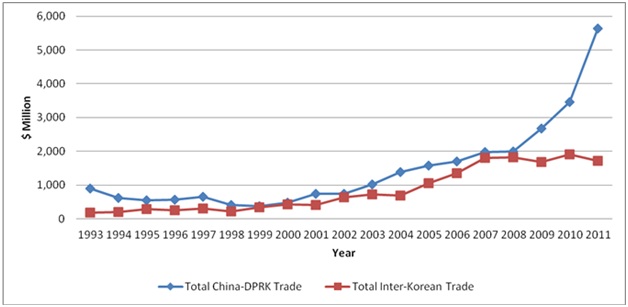

North Korea’s trade dependency on China has skyrocketed in the past year, reaching US$5.63 billion in 2011, an increase of 62.5 percent from $3.46 billion in 2010. Meanwhile, trade with South Korea, which is North Korea’s second largest trading partner, dropped by ten percent in 2011 to $1.71 billion. As a result, North Korea’s trade dependency on China appears to have risen dramatically. Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency(KOTRA) figures suggest an increase from 42 percent in 2008 to over 70 percent in 2011. Noland and Haggard suggest a lower level of dependency, but even if the level of North Korea’s trade dependency (as reflected in the officially recorded numbers from China, which themselves do not reflect smuggling or barter transactions that according to some rumors exceeded officially recorded trade six years ago) is overstated, this trend represents a dramatic shift from a situation in which growth in Sino-DPRK and inter-Korean trade matched each other through 2008 to a situation in which China’s trade with North Korea more than triples the level of inter-Korean trade, generated almost exclusively via operations at the Kaesong Industrial Complex

Figure 1. China-DPRK Trade vs. Inter-Korean Trade (1993-2011)

Source: Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency, Korea International Trade Association, ROK Ministry of Unification

So what are the strategic implications of North Korea’s increasing trade dependency on China? Does North Korean dependency on China increase China’s leverage to influence North Korea, and if so, to what end? We can consider at least three interpretations:

Some South Koreans might interpret this graph as evidence that China is using its growing economic advantage in the North as a tool by which to prevent Korean reunification, or they might argue that China is strengthening its economic grip on North Korea with the intent of stabilizing North Korea economically so as to bolster the status quo. But while China’s objective may be to shore up North Korean stability, it is still doubtful that China’s economic influence is sufficient to keep North Korea afloat or to prevent internal political divisions from dividing North Korea politically.

At least one prominent Chinese analyst, Shi Yinhong , seems to argue the opposite that China’s policy toward the North has been characterized by “largely unconditional political support” accompanied by a “refusal to extend generous economic aid.” He sees China as holding back on assistance to the North as a way of cultivating Chinese leverage, but in the end concludes that North Korean volatility has cornered China into a policy that is at odds with both the United States and South Korea. Chinese desires for North Korean stability appear unlikely to benefit China strategically, even if they are realized, without a change in direction in the North. The one exception may be China’s clear strategic motive for increasing its foothold and presence at the Rason port, which provides China’s landlocked Jilin province with access to the sea.

Another possible interpretation is that not much has changed in the China-DPRK relationship except that the high price of oil is making it more expensive for China to fulfill its commitments to the DPRK. And the greater the cost that China must bear in support of a failing North Korea, the better the likelihood that China will finally reach a turning point, at which time it will be clear to China that the costs of the status quo are higher than the benefits of a transformed North Korea. But this view also requires both imagination and faith that China’s next generation leadership will identify and fix the contradictions inherent in China’s approach to the Korean peninsula so as to prioritize cooperation with South Korea and the United States over strategic mistrust.

In fact, Noland and Haggard have just released a report that argues North Korea’s internal governance is the main factor that is suppressing growth in China-DPRK trade, as well as North Korea’s trade with the rest of the world. In theory, external parties should cooperate with each other and with internal reforming constituencies inside North Korea to pursue measures that would result in a transformation in North Korea’s economic governance practices, with potential implications for economic growth that would surely result in North Korean prosperity—and normality. But prosperity is apparently still too high a price to pay in North Korea if it comes at the cost of political control.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store