Oceans and Climate Change: A Bleak Outlook

November 3, 2015 1:59 pm (EST)

- Post

- Blog posts represent the views of CFR fellows and staff and not those of CFR, which takes no institutional positions.

More on:

Coauthored with Naomi Egel, research associate in the International Institutions and Global Governance program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

As the Paris climate meeting rapidly approaches, the preparatory discussions have been remarkably silent on the crucial links between global warming and the health of the world’s oceans. This is a missed opportunity to galvanize global political will behind significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Last week, the U.S.-based Consortium for Ocean Leadership and the European Marine Board released an Oceans Climate Nexus Consensus Statement, drawing attention to how integral the oceans are to the earth’s climate system—and to the survival of life on our planet. The statement calls on parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to deliver a strong agreement at Paris that includes ambitious mitigation targets that will limit further damage to the ocean and its ecosystems. It also calls on funders to fund oceans research, so that scientists can better comprehend the magnitude of climate change and propose ways to mitigate and adapt.

Though the oceans cover 71 percent of the Earth’s surface, we still understand very little about how they work. But we do know that they are fundamental to the climate system, serving as our planetary life support system. As humanity has continued to spew out greenhouse gasses, the oceans have been working overtime to buffer us from the consequences. Since the start of the industrial revolution, the oceans have absorbed 25 percent of human emissions of carbon dioxide, while producing half of the world’s oxygen—more than all of the world’s rainforests combined. But all the extra CO2 uptake comes at a cost. The increased acidity of the oceans is already making it hard for microorganisms, crustaceans, and mollusks to build skeletons and shells. Unless current trends are reversed, complex marine food webs could collapse entirely.

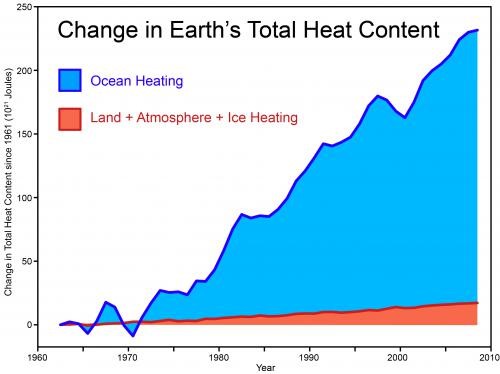

But the oceans aren’t just getting more acidic. They are also warming disastrously. A close look at the world’s oceans shows that we’re only seeing the tip of the iceberg when we focus on the atmospheric and terrestrial impacts of rising temperatures. That’s because most of the heat generated by the greenhouse effect is being absorbed by the ocean. The good news is that the world’s oceans are not just a carbon sink, but a heat sink as well: they hold one thousand times more heat than the atmosphere. The bad news is that while the atmosphere loses heat very quickly, once the oceans heat up, they won’t cool back for decades—even centuries—even with dramatic declines in emissions. And we don’t know when they’ll reach their carrying capacity.

The warming of the world’s oceans has potentially catastrophic implications for marine biodiversity. If it continues, it could render entire regions of extreme heat, such as the Persian Gulf, devoid of marine life. Combined with rising ocean acidification, warming will disrupt marine ecosystems. Humans will quickly feel these effects: oceans are a critical food source for much of the world and of course, rising sea levels already threaten low-lying and island states. More warm water in the tropics also means a larger hurricane generation zone, which could threaten these states, as well as global trade (nearly 90 percent of global trade takes places involves shipping). And as the ocean heats up, it will alter rainfall patterns: 86 percent of global evaporation and 78 percent of global precipitation occur over the ocean.

Still, there is a slowly growing recognition that we can’t tackle climate change if we ignore the role of the oceans. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had a chapter devoted to oceans (previous reports only mentioned it in passing). Secretary of State John Kerry has made the oceans a foreign policy priority, elevating the issue both in the United States and internationally. At the second Our Ocean summit, hosted by Chile last month, attendees announced over eighty new initiatives to protect the world’s oceans. The United States is also currently developing its first integrated marine plans for its coastal zones, to be released in 2016.

In additional to the Oceans-Climate Nexus Consensus Statement, a group of forty-two organizations will host the annual World Oceans Day on December 4 at the UNFCCC conference in Paris to highlight the connection between global warming and marine health and propose solutions. The coalition calls on UN member states to conserve and sustainably manage coastal ecosystems (including mangroves, seagrass beds, and salt marshes), both to mitigate climate change—by providing natural carbon sinks—and to adapt to its consequences—by creating natural defenses against rising seas, storms, and flooding.

Despite these efforts, the oceans remain a fringe issue when it comes to global efforts to tackle climate change. Existing initiatives—and funding—are woefully inadequate to tackle to scope of the challenge. A quick scan of the intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs) that countries have prepared for Paris reveals virtually no mention of oceans—much less an integrated global plan to protect them. Oceans must feature more prominently in any agreement that comes out of Paris. The links between oceans and climate change only underscore how essential it is to cut carbon emissions to ensure the sustainability of the planet. Greater investment in ocean research can also improve forecasting, reducing the uncertain effects of climate change, and potentially saving many lives.

At Paris, states and other stakeholders should scale up efforts and funding to study the relationship between oceans and climate change. And although it is too late to alter INDCs before Paris, they should be revised in five years (as recently suggested by France and China), to include ocean-centered climate mitigation efforts. For too long, oceans health and climate change have been treated as distinct issues. Paris provides an opportunity to fix that, and in doing so, take a big step toward fixing our planet.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store