- China

- RealEcon

-

Topics

FeaturedInternational efforts, such as the Paris Agreement, aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But experts say countries aren’t doing enough to limit dangerous global warming.

-

Regions

FeaturedThe 2021 coup returned Myanmar to military rule and shattered hopes for democratic progress in a Southeast Asian country beset by decades of conflict and repressive regimes.

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

FeaturedPlease join us for two panels to discuss the agenda and likely outcomes of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Summit, taking place in Washington DC from July 9 to 11. SESSION I: A Conversation With NSC Director for Europe Michael Carpenter 12:30 p.m.—1:00 p.m. (EDT) In-Person Lunch Reception 1:00 p.m.—1:30 p.m. (EDT) Hybrid Meeting SESSION II: NATO’s Future: Enlarged and More European? 1:30 p.m.—1:45 p.m. (EDT) In-Person Coffee Break 1:45 p.m.—2:45 p.m. (EDT) Hybrid Meeting

Virtual Event with Emma M. Ashford, Michael R. Carpenter, Camille Grand, Thomas Wright, Liana Fix and Charles A. Kupchan June 25, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

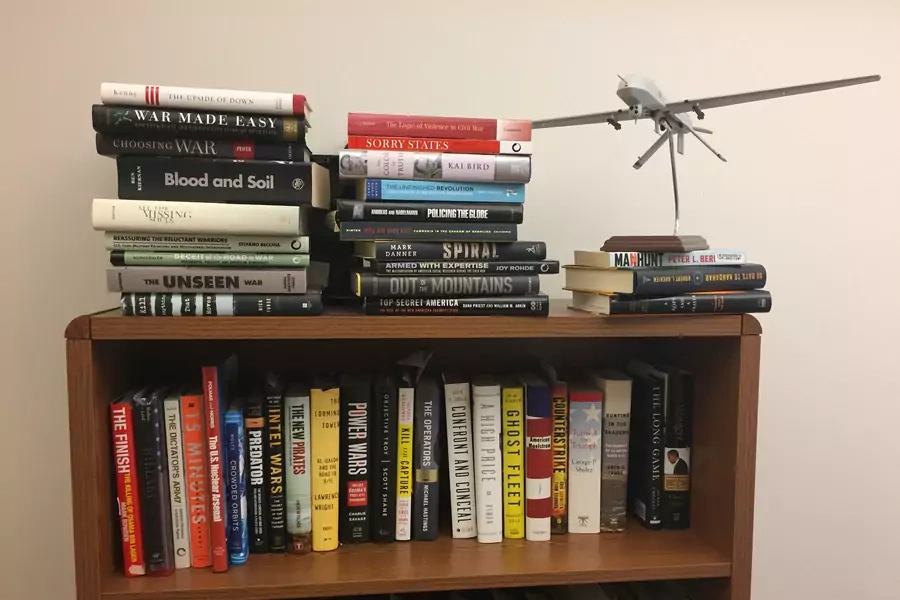

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

Questioning Obama’s Drone Deaths Data

Months after promising to release the number of civilians that have been killed in U.S. lethal counterterrorism operations outside of "areas of active hostilities," the Obama Administration today released its count in a report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. According to the numbers provided, there were 473 "strikes" [presumably this includes both manned and unmanned aircraft conducted by both the CIA and the U.S. military] which killed between 2,372 and 2,581 combatants, and between 64 and 116 civilians.

According to the numbers that we have provided since our Reforming U.S. Drone Strike Policies report in January 2013, the numbers of strikes in non-battlefield settings and fatalities of both combatants and civilians is much higher. As of today, there have been approximately 578 strikes—50 under George W. Bush, 528 under Obama, which have cumulatively killed an estimated 4,189 militants and 474 civilians. This information is fully presented in the chart below with the sources used.

Sources: New America Foundation (NAF); Long War Journal (LWJ); The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ)

** Based on averages within the ranges provided by the organizations monitoring each country as of July 1, 2016.

How Not To Estimate and Communicate Risks

Estimating and translating the probability of an event for decision-makers is among the most difficult challenges in government and the private sector. The person making the estimate must be able to categorize or quantify a likelihood, and willing to relay that analysis to the decision-maker in a way that is comprehensible and timely. The decision-maker then must consider the probability within the context of other information, and subsequently consider the trade-offs between one course of action over another. The ultimate goal of perceiving and communicating risks is to best assure any institution has managed those risks and made the most sound choice possible in the time allotted.

There were fascinating paragraphs hidden in a recent NASA Office of Inspector General (OIG) report—NASA’s Response to SpaceX’s June 2015 Launch Failure: Impacts on Commercial Resupply of the International Space Station—about the inherent challenges that come with estimating probabilities. On June 28, 2015, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying a cargo resupply mission to the International Space Station (ISS) failed two minutes after liftoff. The rocket along with a capsule and $118 million worth of NASA cargo it was carrying was destroyed. SpaceX later determined through recovering parts of the Falcon 9 and telemetry analysis that the likely cause was a “strut assembly failure” during the rocket’s second stage.

The June 2015 event had been the second commercial resupply mission failure in eight months, following a failed liftoff of an Orbital ATK’s third mission (termed, Orb-3). Given that SpaceX and Orbital are the only two commercial space providers to have successfully supplied the ISS—a third, Sierra Nevada Corporation, was awarded resupply contracts, but has not launched yet—the OIG examined NASA’s response to the SpaceX failure and its efforts to reduce the risks associated with future missions.

On pages twenty and twenty-one of the report, the OIG reveals that “there is no integrated presentation or package that documents all risk areas for a given launch. Instead, separate presentations are used to determine the ‘acceptable’ risk posture—a term that evolves frequently.” The report then contains the following passage:

Although the flexibility in determining and altering the nature of an acceptable risk posture has some benefits, it may also introduce confusion into the process. For example, senior NASA officials have stated that high levels of risk for cargo missions are tolerable, noting the expected risk of mission failure for a typical [Commercial Resupply Services] launch is one in six. However, as stated in the Orb-3 Independent Review Team’s report, NASA engineering personnel expressed significant concerns about the Orb-3 launch vehicle’s engines and the recent failures Orbital had experienced on test stands, characterizing the likelihood of mission failure for Orb-3 as "50/50." In contrast, the ISS Program’s risk matrix reflected the risk of Orb-3 engine issues as "low" and assigned a subjective risk of "elevated but acceptable."

Although according to some ISS Program officials NASA management is generally willing to accept heightened risk for cargo missions, it is unclear whether senior NASA management clearly understood the increased likelihood of failure for the Orb-3 mission. Even so, the disparity between 50/50 and one in six for the same mission raises questions about the adequacy of communication between the engineers and top program management [emphasis added].

Such estimates are inherently subjective, but nevertheless they captured somebody’s degree of belief of the probability of mission failure. As we know from the work of scholars like Baruch Fischoff and Richard Zeckhauser that combining numerical estimates and probability expressions leads to confusion among decision-makers. Moreover, when people are asked to assign a numerical probability to phrases like “low” or “elevated but acceptable” they will offer a wide range of numbers. To mitigate against such ambiguity, a U.S. Intelligence Community directive assigns percentage ranges for probability expressions. “Unlikely” to “improbable” are 20 to 45 percent, while “very likely” and “highly probable” are 80 to 95 percent. The Department of Defense uses a different method for assessing risks, which is posted below:

Naturally, any decision-maker would react differently, and potentially opt for an alternative choice, to a 17 percent or 50 percent probability—the contrasting “one in six” and “50/50” estimates that were found by the NASA OIG.

In 1964, Sherman Kent, a pioneer in intelligence analysis, published an important piece—“Words of Estimative Probability”—in the CIA’s in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence. Kent reviewed the ambiguous words, phrases, and numbers that analysts have used to translate likely outcomes for policymakers. Kent wrote that “once the community has made up its mind in this matter, it should be able to choose a word or a phrase which quite accurately describes the degree of its certainty; and ideally, exactly this message should get through to the reader.” Apparently, there was no such standard used between the two commercial space providers and the ISS program managers, introducing needless uncertainty upon which decisions were made.

Merkel’s Erdogan Problem

Sabina Frizell is a research associate in the Civil Society, Markets, and Democracy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

This week alone, Turkey jailed two journalists on trumped-up terrorism charges, threatened to sue a professor for insulting President Erdogan, and pushed forward the same construction project that sparked massive anti-government protests in 2013. As Turkey’s democracy deteriorates, German-Turkish relations have gone from tense to outright hostile. Chancellor Angela Merkel is vacillating on whether to hold firm to core European Union (EU) values of democracy and human rights or appease Turkey. She can either continue to waver, tacitly accepting Erdogan’s behavior, or send Turkey a strong signal that its human and civil rights violations are unacceptable.

Germany and Turkey are bound by over fifty years of migration. Starting in the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Turks began immigrating to Germany under its supposedly temporary Gastarbeiter (guest worker) program—but many stayed beyond the intended one-to-two years, bringing their families and settling for good. Today Germany has over three million citizens and residents of Turkish descent, making Turks the country’s largest immigrant group.

Amid the ongoing refugee crisis, migration again ties the two countries together. Germany and Turkey were the primary negotiators of the EU-Turkey migrant deal, which set up a one-for-one trade of asylum seekers for Syrian refugees. The EU also pledged €6 billion for Turkey to help settle migrants, and raised the possibility of visa-free travel for Turks. Though widely declared a human rights catastrophe (and rightly so), the deal is critical to Merkel’s already-waning popularity at home—and its success in stemming the flow of migrants hinges on Turkey’s cooperation. As a result, Merkel’s government developed some degree of dependency on Turkey, despite Erdogan’s many affronts to democracy and ever-tightening grip on power.

In this context, Germany has at times compromised its own values rather than strain its relationship with Turkey, as in the case of the charges against German comedian Jan Böhmermann. After Böhmermann read a crude poem insulting Erdogan on television, the Turkish government filed a criminal complaint demanding that Germany charge him for violating an archaic German law from the 19th century that prohibits slander of foreign heads of state. Though the law leaves some room for interpretation—it applies to slander, but not satire, riding a fine and subjective line—Merkel approved a criminal prosecution against Böhmermann, and even apologized for the poem. With Turkey extending limitations on free speech beyond its borders, many Germans were outraged, saying Merkel was kowtowing to Erdogan for fear that he might back out of the migrant deal.

But the Bundestag has also proved ready to challenge Turkey. This month, the parliament voted almost unanimously to officially recognize the Ottomans’ slaughter of some 1.5 million Armenians during World War I as genocide. Germany follows over twenty countries that have passed similar resolutions, but its voice is especially significant given both its own history, and its complicity with the Armenian genocide as a then ally of the Ottoman Empire (which the resolution acknowledges, calling Germany “partially responsible.”) The Turkish government, which vehemently denies the killings constitute genocide contrary to almost all historical assessments, called Germany’s vote a “test of friendship” and within hours recalled their ambassador to Turkey—warning the move was just a first step. Judging by Turkey’s short memory of other countries’ rulings on the genocide, the threats will likely die down. But the episode nevertheless rattled the countries’ fragile bond.

Germany is attempting a precarious balance with Erdogan, and should adopt a more coherent stance—one that recognizes his government’s transgressions consistently, not selectively. To start it should make aid, not just visa-free travel, contingent on Turkish respect for human rights, especially those of the migrants. With a wave of far right parties gaining momentum across Europe and the refugee deal falling apart, Merkel’s center right Christian Democratic Union party may be in jeopardy. Recent polls show support for the bloc is at an all-time low, while distrust of Turkey is rising. Merkel’s ability to manage relations with Ankara will be one crucial piece of maintaining public support.

Bargaining and Military Coercion: A Conversation with Todd Sechser

Today, I spoke with Todd Sechser, Associate Professor in the Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics at the University of Virginia. We spoke about his important new article in Journal of Conflict Resolution, “Reputations and Signaling in Coercive Bargaining,” his next book with Matthew Fuhrmann, Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming), and why the United States has such a poor record at coercive diplomacy. Todd also provides advice for young scholars in international relations. Listen to my conversation with one of the smartest scholars doing policy-relevant research on coercion, reputations, and U.S. foreign policy.

New Commander, New Rules

Harry Oppenheimer is a research associate for national security at the Council on Foreign Relations.

The U.S. military mission in Afghanistan has been subject to restrictive rules of engagement that prohibited targeting the Taliban directly unless they posed a threat to U.S. personnel, or an extreme threat to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF). Reportedly, this has changed. The recent news was the first major policy change for the Afghan War since General John Nicholson took over command exactly one hundred days before the announcement on March 2, 2016. Combined with today’s story that North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) bases will remain open in Afghanistan into 2017, Nicholson has latitude that would be the envy of his predecessors.

Flexibility over war plans is something that General John F. Campbell, Nicholson’s predecessor, called for publically in Senate hearings but could never achieve. After leaving Afghanistan, reports leaked that Campbell wanted to strike the Taliban directly and created enemies within the Department of Defense (DoD) in the process. Last week’s news makes such direct action possible. But there is a larger story as well—the White House appears to be responding to the concerns of the commander on the ground.

When the then–lieutenant general Nicholson testified at his confirmation hearings in January he reiterated the importance of coalition close air support (CAS) and logistical and intelligence enablers for the ANDSF. His written testimony outlined his understanding entering the position: “Although their capabilities continue to grow as DoD fields additional planned aviation and intelligence, security, and reconnaissance (ISR) enablers to the ANDSF, I’ve been informed that there are still many requests for coalition enablers.” However, he added, “in the near term, as their CAS capability grows with the fielding of the A29 and additional rotary wing assets, I expect those requests to diminish. Over the long term, the most important capability we can provide them are the systems and procedures we put in place to ensure their sustainability.”

This preliminary view came with a promise that in the first three months in command he would undertake a comprehensive review of the situation in Afghanistan and report back to senior leaders. This assessment would come, “after I have had the opportunity to get first hand insight on the situation in Afghanistan.”

Regrettably, the Taliban have been encouraged by a highly successful 2015 that saw them control more territory than they ever have since the 2001 U.S. invasion. Recently, they have had numerous victories in southern Afghanistan. The day before the announcement of the expanded U.S. role, the special inspector general for Afghan reconstruction warned that Taliban gains jeopardized the efforts of the United States in the past decade.

Now President Barack Obama has eased the restrictions on airstrikes in direct support of ANDSF, something that he has been loathed to do despite numerous suggestions from former military leaders and national security experts. ABC News reports that Nicholson, “will now be allowed to determine when American forces should advise and assist conventional Afghan Army units, something that until now had only been allowed for American special operations forces working with Afghan special operations forces.” News that NATO bases will remain open despite planned troop reductions will give Nicholson further flexibility to gauge force size and placement.

While we cannot see Nicholson’s report to the president, many have speculated as to its contents. It is unlikely a coincidence that these policy changes come exactly one hundred days into his command. Here the proof may be in the pudding—Nicholson has seen the state of the Afghan military and the reduction of direct support he expected in March is clearly unrealistic. That is the only assessment one can imagine would push the administration to relax restrictions on a war it wanted over long ago.

Hopefully this is a sign of good things to come—the best military advice, in this case from the vastly experienced Nicholson on the ground, translating directly into policy changes authorized by the White House. Maybe Nicholson learned from his predecessor and went about advocating for new authority with greater political acumen. The upside is that is the influence he could have over the direction of the Afghan War and the trust he has been given by civilian leadership.

Online Store

Online Store