- China

- RealEcon

- Topics

-

Regions

FeaturedThe 2021 coup returned Myanmar to military rule and shattered hopes for democratic progress in a Southeast Asian country beset by decades of conflict and repressive regimes.

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

Featured

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

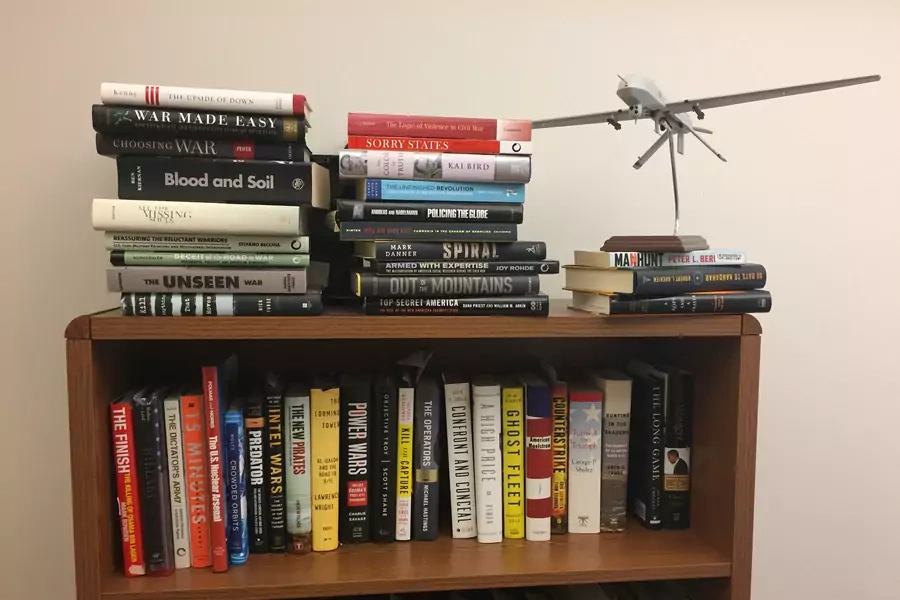

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

Being Honest About U.S. Military Strategy in Afghanistan

Today, the commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, General John “Mic” Nicholson, testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC). Though it remains the longest war in American history, the ongoing military campaign in Afghanistan received little attention during the presidential race and even less since President Trump entered office. You may recall that in December 2009, President Obama authorized the deployment of 30,000 U.S. troops to Afghanistan, bringing the total to 97,000. The vast majority of those troops have returned home; there are 8,400 troops in country now (plus 26,000 military contractors, 9,474 of whom are U.S. citizens).

Since Obama’s Afghan surge, the security situation has deteriorated markedly. Nearly 1,700 U.S. troops were killed while serving there, the annual number of civilians casualties (the majority of whom were killed or injured by the Taliban) increased from 7,162 (in 2010) to 11,418 (in 2016), the number of jihadist groups grew (including the creation of a satellite Islamic State outpost)—all while the Taliban expanded its control and influence over more territory than at any other point since 9/11. That last metric is especially revealing, given Obama’s vow that the additional forces would “reverse the Taliban’s momentum.” This has not happened.

During today’s hearing, SASC Chairman John McCain asked Nicholson outright, “In your assessment, are we winning or losing?” Nicholson replied, “We’re in a stalemate.” Nicholson added that his command’s objective was to “destroy al-Qaeda” in Afghanistan, and that the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) were doing most of the direct fighting to accomplish this. However, he noted that he was a “few thousand” troops short of what was needed to adequately train and advise the ANSF. Though Nicholson did not say so explicitly, the implication was that just a few more troops could turn the tide. But it is hard to imagine how these additional forces would improve the security situation in any lasting way.

The most telling moment in the SASC hearing came when Nicholson remarked that plans were being developed to “find success” in Afghanistan within the next four years. That would mark a full twenty years of direct U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan. Since the first Central Intelligence Agency paramilitary teams entered Afghanistan in November 2001, 2,350 servicemembers have given their lives and almost $900 billion in taxpayers’ money has been spent. Meanwhile, the country is less politically stable and less secure from all forms of insurgent and criminal predation. No one can say how or when this largely forgotten war will end, but “finding success” certainly should begin with some realism, honesty, and a corresponding adjustment in U.S. expectations and objectives.

Failed States, Rebel Diplomats, and Pirates: A Conversation with Bridget Coggins

Bridget Coggins has a fascinating body of work that examines often overlooked non-traditional security issues and uses fact-based research to counter even the most pervasive conventional wisdom.

Ending the South Sudan Civil War: A Conversation with Kate Almquist Knopf

Kate Almquist Knopf, director of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies at the National Defense University, is the author of a recent Center for Preventive Action report on Ending South Sudan’s Civil War. We discussed the crisis in South Sudan and her outside-the-box proposal to address it, which involves establishing an international transitional administration for the country. She also offered some near-term recommendations for the Trump administration.

Knopf shares her advice for young professionals, and offers a fresh take on how the relationship between state and society could shift political institutions within Africa. Listen to my conversation with one of the world’s leading experts on South Sudan, and follow her on Twitter @almquistkate.

Fifteen Questions Trump Should Answer About His “Safe Zones”

Yesterday, the White House released the readout of a call between President Donald Trump and the King of Saudi Arabia, Salman bin Abdulaziz al Saud. The statement featured this remarkable statement: “The President requested and the King agreed to support safe zones in Syria and Yemen, as well as supporting other ideas to help the many refugees who are displaced by the ongoing conflicts.”

During the presidential campaign, Trump, as well as Mike Pence, repeatedly endorsed the creation of safe zones in Syria, without adding any clarification. Trump proclaimed that unnamed Middle East countries would pay for the “big, beautiful safe zone” in Syria, while Pence during the vice presidential debate proclaimed they would “create a route for safe passage” and “protect people in those areas, including with the no-fly zone.” Five days later, when asked about his running mate’s position Trump declared flatly: “He and I haven’t spoken, and I disagree.”

Political campaigns are consequence-free environments, but statements made while serving as chief of state should reflect actual government policy. If President Trump is now serious about authorizing the U.S. armed forces to implement safe zones (as indicated by his request to the Saudi monarch), he and his senior aides must clarify exactly what he means by this new, expansive, and poorly conceived military mission.

I have written about no-fly zones and safe zones for more than fifteen years. But rather than re-package previous analysis, here are fifteen questions that Congress, journalists, and citizens should expect the Trump administration to answer:

What is the ultimate political objective of the safe zones? For example, will they provide temporary humanitarian refuge for internally displaced persons, or leverage for a brokered peace agreement?

What is the domestic legal basis for them?

As the sovereign government of Syria will presumably oppose them, what is the international legal basis?

Where exactly within Syria or Yemen will they be located, and why were those locations chosen?

Will non-combatants as well as rebel groups residing within the safe zones be protected? If not, how will residents be vetted, and who will do the vetting?

Will those residing within safe zones be protected from all forms of harm, including aerial bombing, artillery shelling, small arms fire, sniper fire, starvation, and lack of clean drinking water and sanitation?

Will those residing within safe zones be protected from harm by all perpetrators (including by Russian fighter-bombers and U.S.-backed rebel groups in Syria, or by indiscriminate Saudi airstrikes in Yemen)?

Which countries will provide the military forces for the many tasks required to enforce the safe zones (suppression of enemy air defenses, logistical support, combat search and rescue, etc.)?

Which groups or states will provide humanitarian assistance and be allowed access to those residing in the safe zones?

Critically, who provides the ground forces to enforce and patrol the safe zones?

Which nearby countries will allow safe zone forces basing and overflight rights, and for which missions specifically?

Who has ultimate command authority for however many countries contribute forces?

What military doctrine and rules of engagement will guide those forces enforcing the safe zones?

Will force be used to prohibit arms groups from using the safe zones to shield their activities or recruit fighters, as they inevitably will try to do?

Who pays, and for how long?

Obama’s Final Drone Strike Data

As Donald Trump assumes office today, he inherits a targeted killing program that has been the cornerstone of U.S. counterterrorism strategy over the past eight years. On January 23, 2009, just three days into his presidency, President Obama authorized his first kinetic military action: two drone strikes, three hours apart, in Waziristan, Pakistan, that killed as many as twenty civilians. Two terms and 540 strikes later, Obama leaves the White House after having vastly expanding and normalizing the use of armed drones for counterterrorism and close air support operations in non-battlefield settings—namely Yemen, Pakistan, and Somalia.

Throughout his presidency, I have written often about Obama’s legacy as a drone president, including reports on how the United States could reform drone strike policies, what were the benefits of transferring CIA drone strikes to the Pentagon, and (with Sarah Kreps) how to limit armed drone proliferation. President Obama deserves credit for even acknowledging the existence of the targeted killing program (something his predecessor did not do), and for increasing transparency into the internal processes that purportedly guided the authorization of drone strikes. However, many needed reforms were left undone—in large part because there was zero pressure from congressional members, who, with few exceptions, were the biggest cheerleaders of drone strikes.

On the first day of the Trump administration, it is too early to tell what changes he could implement. However, most of his predecessor’s reforms have either been voluntary, like the release of two reports totaling the number of strikes and both combatants and civilians killed, or executive guidelines that could be ignored with relative ease. Should he opt for an even more expansive and intensive approach, little would stand in his way, except for Democrats in Congress, who might have newfound concerns about the president’s war-making powers. Or perhaps citizens and investigative journalists, who may resist efforts to undermine transparency, accountability, and oversight mechanisms.

Less than two weeks ago, the United States conducted a drone strike over central Yemen, killing one al-Qaeda operative. The strike was the last under Obama (that we know of). The 542 drone strikes that Obama authorized killed an estimated 3,797 people, including 324 civilians. As he reportedly told senior aides in 2011: “Turns out I’m really good at killing people. Didn’t know that was gonna be a strong suit of mine.”

Online Store

Online Store