- China

- RealEcon

- Topics

-

Regions

FeaturedThe 2021 coup returned Myanmar to military rule and shattered hopes for democratic progress in a Southeast Asian country beset by decades of conflict and repressive regimes.

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

Featured

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

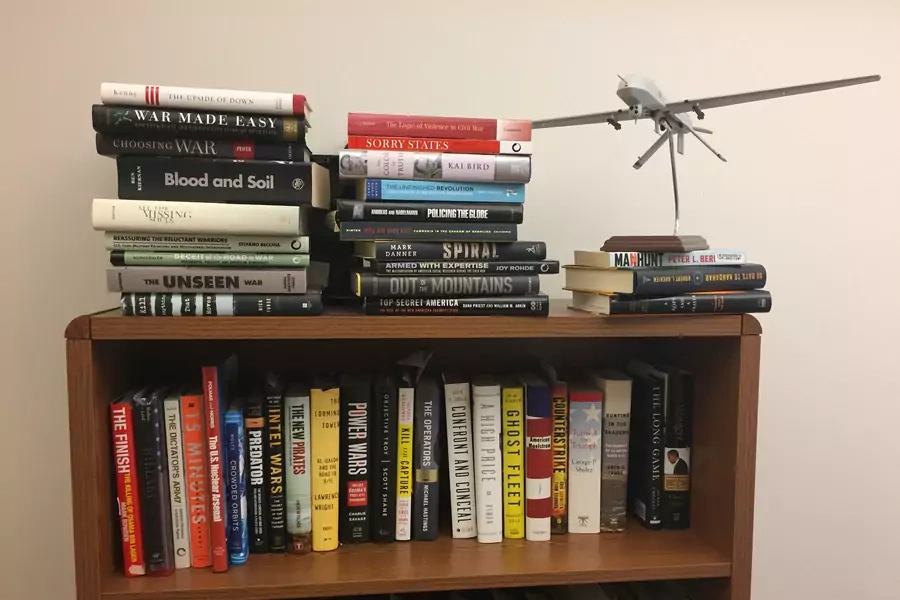

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

Superforecasters, Software, and Spies: A Conversation With Jason Matheny

This week I sat down with Dr. Jason Matheny, director of the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA). IARPA invests in high-risk, high-payoff research programs to address national intelligence problems, from language recognition software to forecasting tournaments to evaluate strategies to “predict” the future. Dr. Matheny shed light on how IARPA selects cutting-edge research projects and how its work helps ensure intelligence guides sound decision- and policymaking. He also offers his advice to young scientists just starting their careers.

Listen to a fascinating conversation with the leader of one of the coolest research organizations in the U.S. government, and follow IARPA on Twitter @IARPANews.

How Many Bombs Did the United States Drop in 2016?

This blog post was coauthored with my research associate, Jennifer Wilson.

[Note: This post was updated to reflect an additional strike in Yemen in 2016, announced by U.S. Central Command on January 12, 2017.]

As President Obama enters the final weeks of his presidency, there will be ample assessments of his foreign military approach, which has focused on reducing U.S. ground combat troops (with the notable exception of the Afghanistan surge), supporting local security partners, and authorizing the expansive use of air power. Whether this strategy “works”—i.e. reduces the threat posed by extremists operating from those countries and improves overall security and governance on the ground—is highly contested. Yet, for better or worse, these are the central tenets of the Obama doctrine.

In President Obama’s last year in office, the United States dropped 26,172 bombs in seven countries. This estimate is undoubtedly low, considering reliable data is only available for airstrikes in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and Libya, and a single "strike," according to the Pentagon’s definition, can involve multiple bombs or munitions. In 2016, the United States dropped 3,028 more bombs—and in one more country, Libya—than in 2015.

Most (24,287) were dropped in Iraq and Syria. This number is based on the percentage of total coalition airstrikes carried out in 2016 by the United States in Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR), the counter-Islamic State campaign. The Pentagon publishes a running count of bombs dropped by the United States and its partners, and we found data for 2016 using OIR public strike releases and this handy tool.* Using this data, we found that in 2016, the United States conducted about 79 percent (5,904) of the coalition airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, which together total 7,473. Of the total 30,743 bombs that the coalition dropped, then, the United States dropped 24,287 (79 percent of 30,743).

To determine how many U.S. bombs were dropped on each Iraq and Syria, we looked at the percentage of total U.S. OIR airstrikes conducted in each country. They were nearly evenly split, with 49.8 percent (or 2,941 airstrikes) carried out in Iraq, and 50.2 percent (or 2,963 airstrikes) in Syria. Therefore, the number of bombs dropped were also nearly the same in the two countries (12,095 in Iraq; 12,192 in Syria). Last year, the United States conducted approximately 67 percent of airstrikes in Iraq in 2016, and 96 percent of those in Syria.

Sources: Estimate based upon Combined Forces Air Component Commander 2011-2016 Airpower Statistics; CJTF-Operation Inherent Resolve Public Affairs Office strike release, December 31, 2016; New America (NA); Long War Journal (LWJ); The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ); Department of Defense press release; and U.S. Africa Command press release.

*Our data is based on OIR totals between January 10, 2016 and December 31, 2016

Turkey-EU Trade on Tenterhooks? Faltering Membership Talks Threaten Economic Ties

Sabina Frizell is a research associate in the Civil Society, Markets, and Democracy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

After yesterday’s assassination of the Russian ambassador, Turkish officials were quick to place blame on Fetullah Gulen, an exiled religious leader and one of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s strongest critics. Erdogan is sure to use the attack as yet another justification to silence dissenting voices in the name of security. His ongoing crackdown further diminishes Turkey’s prospects for joining the European Union (EU), following the European Parliament’s overwhelming vote on November 24 to suspend membership negotiations.

While the European Parliament’s vote was largely symbolic, it adds urgency to the question of whether, after decades of Turkey’s slow progress toward membership and ten-plus years of stop-and-start negotiations, the EU should continue membership negotiations.

Most analysts have focused on what ending the talks would mean for the EU-Turkey migrant deal, Turkish democracy, and already-deteriorating human rights under Erdogan. However, the effect on trade issues has been largely overlooked. Turkish and EU economies are deeply intertwined despite mounting political tensions. In considering membership negotiations, the EU must take trade into account, as ending talks would undermine these mutually beneficial economic linkages.

Fifty Years in Waiting

Understanding the current crisis requires an appreciation of Turkey’s long, faltering path toward membership—and of the negotiations’ futility. With or without the talks, Turkey is highly unlikely to become an EU member in the foreseeable future. The EU has always been reluctant to grant Turkey membership, due partially to legitimate concerns about governance, but also to cultural and religious prejudice. EU membership negotiations are based on the Copenhagen Criteria, composed of thirty-five chapters outlining the principles and standards with which all candidate countries must comply. Throughout the 2000’s, Turkey made substantial progress on these criteria. It solidified what the EU deemed a “functioning market economy” that could withstand competitive pressure within Europe, and afforded greater freedom and rights to ethnic and religious minorities. But Europe justifiably expressed concern about overly broad antiterrorism laws, insufficient measures to fight corruption, and the lack of an independent judiciary.

However, there is also evidence that Europeans hold Turkey to more stringent standards than other candidate countries. As Turkey made progress on the Copenhagen Criteria, perhaps faster than expected, some European politicians pointed to “cultural differences” and claimed that Turkey is in some indelible way “not a European country.” The hesitation to support Turkey’s membership revealed anti-Muslim sentiment that likely undermined the accession process all along.

In light of this reluctance, Erdogan’s backtracking on democratic progress makes accession nearly impossible. In the past month, Erdogan’s government has gone further than ever to quash dissent by dismissing thousands of workers, shutting down dozens of news outlets, and jailing journalist and opposition leaders. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) looks set to issue a referendum that could allow Erdogan to stay in office until 2029, and Erdogan raised the possibility of reinstating the death penalty—which would be a deal-breaker for the EU.

Trade Matters

Though negotiations are currently at an impasse, they help to maintain fraught but vital trade ties between Turkey and the EU. Without the talks, the cornerstone of their trade relationship, the EU-Turkey Customs Union could crumble, harming both economies.

The Customs Union, established in 1995, eliminated customs duties and other import restrictions on trade between Turkey and the EU. Though several major sectors were exempt, the union was a boon to the manufacturing sector for both parties. It increased trade between the EU and Turkey fourfold and triggered a similar rise in foreign investment flows to Turkey. Research shows that Turkey improved its competitive advantage for dozens of different products since 1995. The union also provided an impetus for broader trade facilitation and customs reform, which helped Turkey open up to the world and achieve 6 to 9 percent growth in gross domestic product (GDP) from 1995 to 2005.

For the EU, Turkey became an increasingly important part of supply chains. German companies especially rely on Turkey to produce unfinished parts of goods that are then imported and incorporated into final products. Germany’s metal, chemical, and automobile sectors all draw heavily on Turkish imports.

Despite its benefits, the Customs Union is an unequal agreement. Ankara is obliged to comply with the EU’s trade agreements with third-party countries and open up to those markets—but as a non-EU member, it is not granted a seat at the negotiating table. This leaves Turkey deprived of the ability to govern its own trade future. The union was intended as an interim step toward full membership. But if the EU takes membership off the table, it is hard to imagine that Erdogan would continue to accept these debilitating conditions indefinitely.

What would happen if membership talks were suspended and the Customs Union abolished? On the EU side, the move would fragment manufactured goods production. For Turkey, the effects would be much more significant. About 60 percent of its exports are to Europe, representing 12.5 percent of GDP. Diminished ties with its top trade partner could threaten not only Turkey’s economy, but its long term security. Research shows that countries with open economies are less likely to experience internal conflict—and given the Syrian civil war’s spillover and Turkey’s ongoing conflict with the Kurds, the country’s security is already tenuous. As Turkey’s security is tied to that of Europe, maintaining stability should be a top priority for the EU.

Recent coverage of EU-Turkey talks tends to ignore consequences for trade, and by extension, Turkish stability. Freezing negotiations and thus endangering the Customs Union would damage Turkey’s already-flailing economy. Amid Turkey’s democratic retreat, it may be too late for Europe to shed its prejudice and seriously consider Turkey’s candidacy. However, ending talks now would be a mistake without a day-after alternative to ensure trade endures.

Why Trump’s Foreign Policy Appointments Matter: A (Second) Conversation with Elizabeth Saunders

I was lucky enough to again be joined by the brilliant Elizabeth Saunders, assistant professor of political science and international affairs at the George Washington University, and currently a Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. We discussed the role that President-Elect Donald Trump’s advisers will play in shaping his approach to foreign policy and response to international crises. Professor Saunders also talks about two of her recent articles published on the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage, “What a President Trump Means for Foreign Policy” and “How Much Power Will Trump’s Foreign Policy Advisers Have?” Follow her on Twitter @ProfSaunders and, if you haven’t already, listen to the conversation we had back in March, “Presidents and Foreign Policy.”

Our conversation this week covers why we should pay attention to the advisers who will have Trump’s ear on foreign policy and national security. Listen to also hear Professor Saunder’s advice for fellow international relations scholars, and her unconventional hope for her research—that it will become less relevant.

The Politics of Proliferation: A Conversation with Matthew Fuhrmann

I spoke with Matthew Fuhrmann, associate professor of political science at Texas A&M University, visiting associate professor at Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation, and one of the most innovative scholars of nuclear proliferation. We discussed Matt’s soon-to-be released book Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). The book was co-authored with University of Virginia associate professor of politics Todd Sechser, whom I spoke with earlier this year.

Matt and I discussed his research on targeting and attacking nuclear programs, the risks of peaceful nuclear proliferation, and the effectiveness of arms control agreements. Matt also recently coauthored a fascinating article with Michael Horowitz and Sarah Kreps, “The Consequences of Drone Proliferation: Separating Fact from Fiction.” Hear Matt’s advice for young political science and international relations scholars, follow him @mcfuhrmann, and listen to my conversation with a policy-relevant international security scholar.

Online Store

Online Store