- China

- RealEcon

- Topics

-

Regions

FeaturedThe 2021 coup returned Myanmar to military rule and shattered hopes for democratic progress in a Southeast Asian country beset by decades of conflict and repressive regimes.

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

Featured

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

What Conflicts Should the Trump Administration Watch in 2017?

Helia Ighani is the assistant director of the Council on Foreign Relations’ Center for Preventive Action.

Today President-elect Donald J. Trump announced his nomination for secretary of state, Rex Tillerson. Tillerson’s nomination, like others that Trump has made to fill national security positions, have garnered controversy and could face contentious Senate confirmation hearings. Yet, whoever leads the State Department, Pentagon, and intelligence agencies, foreign policy professionals across the government will be confronted with numerous unanticipated global crises in Trump’s first year in office. To help policymakers plan for these contingencies, the Center for Preventive Action conducts an annual Preventive Priorities Survey (PPS) to highlight the top thirty potential conflicts that could affect U.S. interests in 2017.

The PPS is a snapshot of the concerns that foreign policy experts had in fall 2016, when the survey was conducted. The first phase of the survey, when we “crowdsourced” to solicit potential conflicts, took place before the presidential election in October. From the nearly two thousand responses we received, we consulted with the Council on Foreign Relations’ in-house experts to identify thirty contingencies. Right before the election in November, we sent the PPS to seven thousand foreign policy experts with the chosen contingencies. We asked them to rank each conflict based on its relative likelihood of occurring in 2017 and expected impact on U.S. interests. This year was unique, as the experts who completed the survey submitted their answers both before and after the election. We suspect that, given the unexpected outcome of the election, experts’ perceptions of the likelihood or impact of some contingencies may have changed once the results were finalized. Due to the anonymity of the survey, however, we are unable to measure whether that was the case.

One striking difference between this year’s annual survey and the eight previous ones is that there are less conflicts identified in the Middle East that are deemed “high priority” for U.S. policymakers. For example, Iraq fell from a Tier I to a Tier II priority for 2017. Compared to last year, four conflicts that were Middle East–centric came off the list and nine new contingencies were added, only one of which was in the Middle East.

Additionally, the PPS highlights nine new potential crises that the Trump administration may have to address, including increased political instability in the Philippines, growing instability and authoritarianism in Turkey, and the spread of civil unrest and ethnic violence in Ethiopia.

Read the full 2017 survey results: cfr.org/PreventivePrioritiesSurvey2017.

In addition to the list of thirty conflicts included in the PPS, there are ten other contingencies worth noting that did not make the cut:

increased gang-related violence in Northern Triangle countries in Central America

escalation of organized crime–related violence in Mexico and potential economic and political instability resulting from U.S. trade and immigration policies

destabilization of Mali by militant groups

an intensification of sectarian violence between Buddhists and Muslim Rohingyas in Myanmar

violence and attacks in Bangladesh against foreigners and secularists

increased political instability in Egypt, including terrorist attacks, particularly in the Sinai Peninsula

potential confrontation with Iran over the collapse of the nuclear agreement

renewed confrontation between Russia and Georgia over South Ossetia or Abkhazia

increased tensions between China and Taiwan

political or economic instability in Saudi Arabia

succession crisis in Algeria

Download the 2017 report, read previous years’ surveys, and get up to speed on all the ongoing conflicts with our Global Conflict Tracker interactive.

Red States and Green Cities: Predictions for Trump-Era Climate Action

Jennifer Wilson is a research associate for national security at the Council on Foreign Relations.

President-Elect Donald Trump’s reported nomination of Scott Pruitt to head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) indicates that his anti–climate change rhetoric was not just campaign bluster. Pruitt, who has a history of fighting EPA regulations, dims any optimism that Trump would take environmentally responsible action to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. While he seemed to have walked back his opposition to the historic climate deal reached in Paris last year, saying that he had an “open mind” on the accord, Trump’s EPA pick seems more in line with his campaign promise to “cancel” the deal.

As president of one of the 196 signatory countries, Trump will lack the authority to cancel the internationally-agreed upon accord, but he can withdraw the United States from it. However, because of the lengthy and likely controversial process of withdrawing from the agreement or its underlying treaty, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Trump is more likely to just refuse to honor the commitments made under the deal. In that case, the Trump administration will fail to take the steps necessary to meet the target emissions reductions. As the United States accounts for 16 percent of global emissions, second only to China, this failure will make it even more likely that the earth’s overall average temperature will rise to potentially disastrous levels. In addition, a U.S. failure to honor the Paris accord may invite other signatories to balk at their own commitments.

Former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg has responded to Trump’s climate denial by promising that U.S. cities could act to combat climate change should the federal government fail to do so. Bloomberg recently wrote that he would “recommend that the 128 U.S. mayors who are part of the Global Covenant of Mayors seek to join” the accord in the place of the United States.

While the constitutional authority of cities to formally join such an international agreement is dubious, this response would not be the first time state or local governments adopted international climate standards when the federal government failed to do so. In fact, in 2005, Bloomberg was one of the 132 mayors who pledged to meet the emissions reduction requirements of the Kyoto Protocol when the Bush administration rejected the agreement. States have also adopted measures far more ambitious than those enacted by Congress, including renewable energy requirements for privately-owned utilities and regional carbon-trading arrangements.

Cities, with their high population density, centers of industry, and streets clogged with cars and trucks, are major sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Local measures to reduce emissions—such as transitioning to renewable energy sources, instituting effective recycling programs, and installing bike lanes—can have a powerful impact on global climate change. The success of these efforts, however, largely depend on support and funding from state leadership. Urban-led efforts to reduce carbon emissions are therefore likely to remain limited, thanks to significant demographic shifts in the past twenty years.

As this year’s election results demonstrate, the political chasm between urban and rural Americans has grown wider. In 2016, 82 percent of urban counties, representing 160 million people, voted more Democratic than in 2004. On the other hand, 89 percent of medium and small counties, representing 67 million Americans, voted more Republican. Such increased polarization calls into question the success that mayors can expect if they do not have the support of their respective state governments. While 67 percent of major U.S. cities have Democratic mayors, 69 percent of state legislative chambers—where anti-climate change legislation originates—are Republican-controlled, and 56 percent of governors are Republican. Moreover, state leaders who oppose environmental regulations will have an ally in Trump’s EPA administrator, a staunch advocate of states’ rights to resist climate change regulations.

States have long adopted policies at odds with federal guidance, including regarding healthcare access, marijuana use, and marriage equality, but with climate change the stakes are considerably higher. Over the next four-to-eight years, efforts to prevent an eventual global cataclysm will buck against this era’s defining political divide. While a dark prospect, some hope can be found in that the universal effects of climate change—from rising coastlines that threaten to drown cities, to extended droughts that could reduce crop yields—may spur support for environmental policies across the rural-urban divide. If not, then urban efforts to comply with the Paris agreement, while necessary to mitigate the ever-growing menace of climate change, may widen the already gaping chasm between urban and rural Americans. The implications of a divided polity may very well jeopardize the long-term climate change solutions on the federal level that are necessary to literally save the planet.

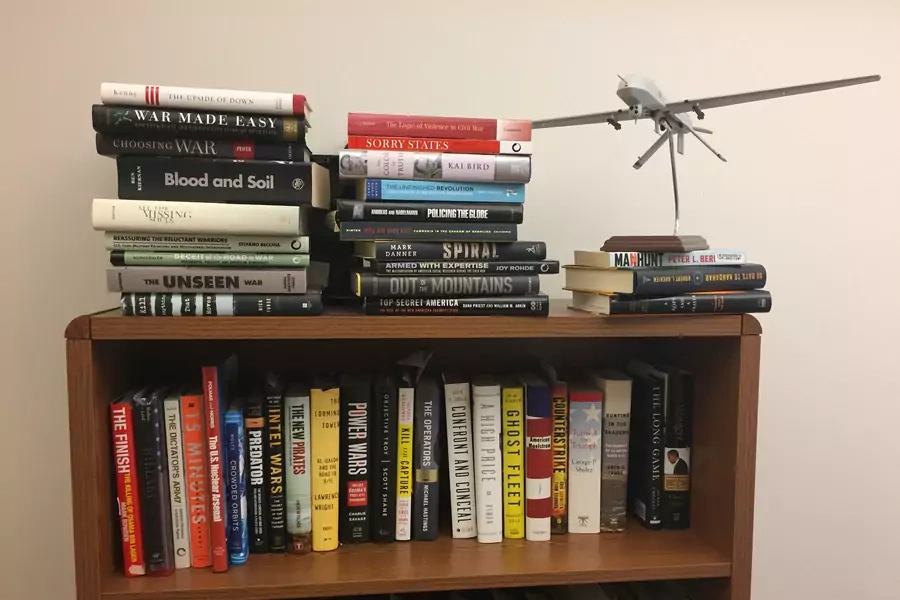

Drone Memos: A Conversation With Jameel Jaffer

This week, I spoke with Jameel Jaffer, inaugural director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. We discussed his new book, The Drone Memos: Targeted Killing, Secrecy, and the Law, and the judicial precedents for targeted strikes and secrecy set during the Obama administration. We also talked about Jameel’s concerns for protecting civil liberties and human rights under the Trump administration. Jameel spoke about his transition from the private sector to the American Civil Liberties Union, where he worked as deputy legal director and headed the Center for Democracy, and also shared his advice for young conscientious lawyers.

In addition to highly recommending The Drone Memos, I would also suggest reading Jameel’s excellent book, co-authored with Amrit Singh, Administration of Torture. Listen to our timely conversation, and follow Jameel on Twitter @JameelJaffer.

Apologies to listeners for the poor sound quality of this podcast; we had some technical difficulties when recording my voice, but Jameel can still be heard loud and clear.

Ending War in South Sudan: A New Approach

Sarah Collman is a research associate in the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.

On December 15, South Sudan will have been at civil war for three years. In 2013, just two years after the country seceded from Sudan and gained independence, fighting broke out in the capital between forces loyal to South Sudanese President Salva Kiir and former Vice President Riek Machar. The political struggle between Kiir and Machar dating back to the 1990s, and divisions within the ruling party, quickly devolved into full-scale civil war, pitting tribal groups against each other. Leaders manipulated ethnic identities and mobilized members of their respective tribes. Forces loyal to Kiir were mainly from the Dinka tribe, and were pitted against Machar’s tribe, the Nuer.

The death toll of the war in South Sudan is at least fifty thousand people, although the United Nations stopped counting in 2014. Privately, humanitarian officials note this is figure is greatly underestimated. Other news outlets estimate the figure could be as high as three hundred thousand people killed. In three years, the civil war has displaced 1.8 million people internally and caused 1.1 million people to flee the country. Approximately 40 percent of the population faces severe food shortages, and almost 75 percent is dealing with some degree of food insecurity. Needless to say, the situation is dire.

In a new Center for Preventive Action (CPA) report, Ending South Sudan’s Civil War, author Kate Almquist Knopf, director of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, argues that the only way to save South Sudan is by putting it on “life support.” To ensure the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, she proposes that the United Nations, in coordination with the African Union (AU), establish an international transitional administration to run the country for ten to fifteen years. Instituting a transitional administration, and taking power over the country from current leaders, would be an extreme measure. Almquist Knopf argues, however, that it would provide the “clean break” that South Sudan needs to end fighting between tribal groups, rebuild the economy, strengthen institutions, and heal from three years of civil war and decades of violence. Lessons from other UN transitional administrations—such as those in East Timor, Kosovo, and Liberia—could be applied to shape a more peaceful and inclusive future for South Sudan.

Because the United States played a unique role in fostering the country’s independence, it is well-placed to help guide the transition from civil war. As a road map toward establishing an international transitional administration, Almquist Knopf proposes the United States should:

Foster a negotiated exit for Kiir and Machar, in coordination with South Sudan’s neighbors, using tools such as offering amnesty, pressing the AU to establish a hybrid court, and instituting time-triggered sanctions and an arms embargo through the UN Security Council.

Reach out to Kiir and Machar’s core partisans and family members to defuse spoilers and persuade them to accept the UN and AU administration.

Conduct sustained high-level diplomacy with South Sudan’s neighbors, other states in the region, and the AU to design the international transitional administration and generate support for it.

Conduct a diplomatic campaign with UN Security Council members and donor countries for them to endorse and secure funding for an international transitional administration.

The United States has allocated $1.9 billion in humanitarian assistance to South Sudan since the outbreak of the civil war, and contributes greatly to the UN peacekeeping mission there. The report’s proposed approach would not necessary be more costly. According to Almquist Knopf, investing in an international transitional administration would be more effective than the current U.S. policy approach. It would finally put an end to the violence and offer the people of South Sudan an opportunity to build an inclusive, representative, and legitimate state.

Read Kate Almquist Knopf’s Ending South Sudan’s Civil War for a full analysis of the challenges South Sudan faces and how the United States can help foster a transition out of civil war.

Thinking About Long-Term Cybersecurity: A Conversation With Steven Weber and Betsy Cooper

I had a fascinating conversation with Professor Steven Weber and Dr. Betsy Cooper of the UC Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity (CLTC). We discussed several scenarios that CLTC developed that could emerge over the next five years, like a destabilizing “war for data” where hundreds of firms whose value is primarily data-driven suddenly collapse. We also talk about bridging the gap between the policy and technical realms, and CLTC’s new report, “Cybersecurity Policy Ideas for a New Presidency,” which identifies top priorities for the Trump administration. Professor Weber and Dr. Cooper also offer their advice to young professionals and scholars hoping to work in cyber policy. Listen to my conversation with two leaders about their inter-disciplinary and innovative approach to one of the most pressing policy challenges today.

Online Store

Online Store