The Real Test for Japan’s Political Leaders Lies Ahead

More on:

Ever since the DPJ swept into power last fall, these Upper House elections have been identified as the moment of popular evaluation for Japan’s new ruling party. But they have also been the focal point for a rebound for Japan’s conservatives. Clearly, Sunday’s election outcome proves Japanese voters have no enthusiasm for the idea of a single party dominating their government—no matter what the political stripe.

The final outcome—a failure to capture a majority for the ruling DPJ and an upswing in support for the opposition conservatives, the LDP —brings a moment of realism to Japanese politics. For many, especially in the DPJ, the hope was for legislative dominance in both houses of the Japanese parliament. But this idea itself suggests that Japan can only be ruled if one political party dominates the legislative process.

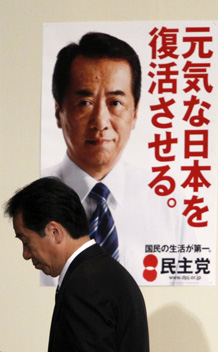

Winning elections is an important part of democracy, and claiming a mandate from the Japanese people is part of the process of changing Japan’s political system. In Tokyo over the past couple of weeks, I sensed a very different energy in this campaign than we all felt last summer when the Japanese public gave the new DPJ a stunning victory at the Lower House polls. The single-member districts were clearly the focal point—and the LDP was all out. Sadakazu Tanigaki, who normally does not exude the kind of charisma and energy that campaigners like to draw on, was bounding throughout the country—looking 20 years younger than his 65 years, and conveying a real sense that the LDP was sorry for letting people down. On the other hand, the DPJ looked as if they were fighting with one hand tied behind their back—and undoubtedly the very apparent differences on the campaign trail between the prime minister and his party leadership and Ichiro Ozawa on the consumption tax issue hobbled their ability to rev up their engines this time around.

But it is also true that Japanese voters—as is usual for Upper House elections—chastened the party in power. This slap on the wrist is more significant today in the context of Japan’s ongoing political transition, and so we have to see how the DPJ and the LDP, as well as these new parties—most notably Minna no To, or Your Party—approach legislative debate over policy differences.

The nervousness over "nejire kokkai" (the twisted Diet) is overblown. The real test of the viability of Japan’s political transition will be how to wean the policy making process off of the idea that only single party dominance makes sense in Tokyo. It makes sense virtually no where else that sports a parliamentary democracy. So Japan’s politicians if they want to lead in policy making will now have to show their mettle. Can they create viable policy alliances on issues of common concern? Or will they be locked forever into electoral battles for power that effectively freeze the country’s policy making?

The challenge for the DPJ, still the ruling party, will be to read the election results and devise a coalition of leadership that will support policies that ought to help the Japanese people. Highest on that list clearly is economic recovery and improving Japan’s long-term fiscal outlook. To do that an effective and forward looking legislative debate will be needed. The question for the next several weeks is whether or not the DPJ can lead that debate rather than be forced into reacting to opposition critiques of their policies.

For the relationship with the United States, the key will be to focus on an agenda setting effort that will define our shared priorities in the years ahead. We need to look beyond our respective electoral cycles to find policy goals that are supported across party lines in both countries.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store