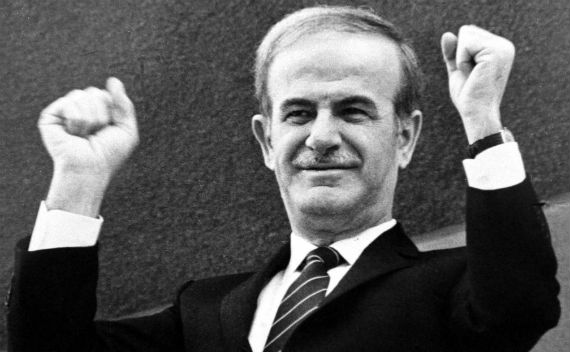

Remembering Hafez al-Assad

November 11, 2011 3:00 pm (EST)

- Post

- Blog posts represent the views of CFR fellows and staff and not those of CFR, which takes no institutional positions.

More on:

Sunday, November 13, marks the 41st anniversary of Hafez al-Assad’s seizure of power in Syria. Since then, Syria has known only one name at the top: Assad. MEM looks back at Assad’s rise and consolidation of power—a story that sheds light on the current unrest in Syria.

Prior to the coup that brought Hafez al-Assad to power, Syrian politics was marked by rampant instability, sectarian turmoil, and frequent coups d’etat. After Syria gained independence from French rule in 1946, the urban Sunni dominated the government. The military was designated as the place for minorities and the uneducated. The Sunnis reserved the top military positions for themselves, and then jostled among one another for supremacy. This became the locus of real power. Between 1949 and 1963, these senior officers engaged in countless military coups--there were three alone in 1949. However, each change of government came after damaging power struggles, the result being the weakening of Sunni ranks.

This opened the door to the Alawites, one of the minorities that had staffed the lower ranks. The Alawites—a small minority within Syria and a branch of Shia Islam—made their play in the 1960s. Between 1963 and 1966, sectarian battles pitting minorities against Sunnis raged within the military and the Baath party that had taken power in 1963.

In February 1966, the Sunni leadership plotted a bloody purge of thirty minority officers within the military. Learning of this plan, a group of mainly Alawi officers took the offensive and successfully carried out their own violent coup, purging the top brass of Sunni officers and clearing out rival officers belonging to other religious groups from the military.

This purge and consequent domination by the Alawis did not bring about stability, however. For the next four years, Hafez al-Assad, at the time an air force commander and defense minister, battled Salah Jadid, a Baath party general, for supremacy. Only when Assad successfully carried out a bloodless coup on November 13, 1970 did the rivalries end. It was Syria’s tenth military coup in seventeen years.

Assad managed to bring stability to a country that had not enjoyed it for a quarter century. He used the secular Baath party as a cover for installing the Alawite minority into important positions throughout the special forces, intelligence and armored corps. Unrest was not tolerated. When riots broke out, they were swiftly ended. The most brutal example of this came when Muslim extremists rose up against Assad in 1982 in the city of Hama. Assad responded with a scorched earth policy. The Syrian military leveled half the city, slaughtering anywhere from ten to forty thousand innocent civilians. Rather than try to hide it, Assad used it as a lesson to others that any challenges to his reign would not be tolerated. And Syrians, while horrified by the brutal nature of his rule, appreciated the relative tranquility that the country had not known following independence.

After three decades of ruling though emergency decree, Hafez al-Assad passed away peacefully in 2000. Upon his death, his son, current president Bashar al-Assad took over the reins. Bashar had not been Hafez’s first choice; the Syrian leader had been grooming his eldest son, Basil, to succeed him. But Basil died in a car accident in 1994, and only then did Hafez look to his younger son as his “heir designate.”

Many hoped that Bashar would fulfill pledges to become a true reformer. Many also thought that because Bashar was a U.K. educated ophthalmologist, not a soldier, married to a British-born Sunni woman, that he would adopt a more liberal, non-sectarian approach. But he never really loosened his father’s iron-fisted grip. As Human Rights Watch reported in 2010, Bashar failed to improve Syria’s human rights record in the decade he ruled. Its report, “A Wasted Decade: Human Rights in Syria during Bashar al-Assad’s First Ten Years in Power,” systematically describes Bashar’s brutal approach, concluding that he had “done virtually nothing to improve his country’s human rights record” and cited Syria’s human rights situation as one of the worst in the world.

The Assad family hold on power is facing its biggest challenge since Hafez seized power 41 years ago. Many respected Hafez because while brutal, he brought stability to Syria—some believe he would have handled the current situation much more deftly. Still, with both he and the stability he brought now gone, Syrian tolerance for brutality is evaporating. The looming question is whether the Assads will make it to their 42nd anniversary in power.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store