Should the currency of the country with a large and growing trade surplus and large and growing reserves depreciate against the dollar?

More on:

On Monday China apparently decided to allow the renminbi to depreciate against the dollar.

Let’s be clear: China generally still has to intervene in the market to keep its currency from appreciating. There is no other way reserves could have risen from $1.9 trillion at the end of September to “over $2 trillion” now.* Traders in China bet on where they believe the government wants the exchange rate to go, not its market-clearing rate. Private Chinese demand for dollar assets still isn’t comparable in scale to China’s $400 billion current account surplus.**

Neil Mellor of the Bank of New York believes that the renminbi’s recent depreciation is a very conscious policy choice:

Since the start of this week, however, there appears to have been a further palpable shift in policy. Following a clear shift in the wording in the latest quarterly monetary policy report and a speech over the weekend by President Hu Jintao (warning that China’s competitiveness and trade strength were being threatened), the PBOC on Monday set the central parity rate of USD/CNY aggressively higher. After four and a half months of sideward trading, the market reacted strongly to this apparent change in attitude by pushing USD/CNY to the top end of its band. The reaction in the NDF market was even more dramatic with the one-year NDF jumping 3.16% (its largest ever one day move in either direction). This upward pressure has continued over the last two days to leave the NDF now forecasting a 6% y/y rise (spurred on today by comments from Vice premier Wang Qishan that China will do all it can to stabilise exports).

If other Asian currencies fall along with China’s currency, the net result would be a broad depreciation of emerging Asian currencies against the dollar more than an improvement in China’s relative position in Asia. And right now Asia is the region of the world economy with the largest current account surplus – and the surplus region that stands to benefit the most from the fall in oil prices.

A global shortfall in demand (and contraction in trade) implies that almost everyone is struggling to maintain (or expand) their market share. China’s exports have stood up well to date (in nominal terms, monthly exports are running about $20b a month above their total in 2007). Monthly exports in 2008 are nearly two times as high as monthly exports in 2005. The scale of China’s recent export boom is hard to exaggerate. But there is little doubt that China’s exports – all of them, not just textile exports – are poised to slow rapidly. Korean exports fell sharply in November. It is hard to believe that China’s exports won’t also soon slow if not start to fall; the latest data on new export orders suggest additional weakness ahead.

That slowdown comes at a time when China’s domestic economy is also slowing – and consequently is extremely unwelcome. China’s latest purchasing managers index (PMI) was as almost bad as the United States’ latest PMI index.

Moreover, China -- like the US – is feeling squeezed by the dollar’s recent appreciation. In real terms, the renminbi has appreciated by far more after it stopped moving up against the dollar that it ever did when it was moving against the dollar. Allowing the renminbi to depreciate against the dollar as the dollar rises would limit China’s real appreciation. It would be consistent with how a basket peg would work.

But it still isn’t the right policy.

China’s basket peg never really was much of a basket peg: it always seemed more like a crawling peg with a variable rate of crawl. China shouldn’t be pegging to a basket either. Given China’s (still) strong balance of payments position, it should be appreciating against a basket -- not keeping its currency constant against a basket.

Remember, China followed the dollar down against the euro in particular from 2002 to 2005. The renminbi’s huge depreciation against the euro – and a tightening of Chinese macroeconomic policy to try to avoid over-heating – contributed to the surge in China’s current account surplus from 2004 on. Even after China moved away from a strict dollar peg, it never quite allowed the renminbi to move enough against the basket to generate a meaningful real appreciation. Renminbi appreciation against the dollar wasn’t fast enough to overcome the dollar’s large slide at that time. In real terms, the renminbi hardly moved – and almost all the appreciation came from the rise in inflation, not a nominal appreciation of the renminbi against a basket of currencies.

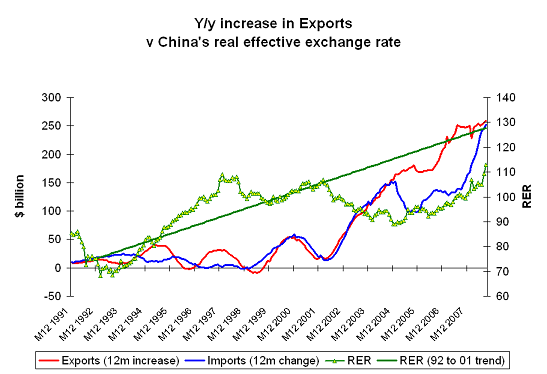

That changed with the dollar’s rally. China in a sense is now getting the real appreciation that it should have gotten in 2004, 2005 or 2006 – back when China’s domestic economy was strong and China risked overheating. But just because China’s drew on exports to turbocharge a strong domestic economy over the past five years doesn’t mean it should draw on exports now to try to offset domestic weakness. Even today China’s real exchange rate is only a bit higher than it was in 2001 -- and China’s underlying economic growth since then (including the huge expansion of its exports) suggests that its real exchange rate should be significantly above its 1998-2001 levels.

(Note the rise in imports in this graph reflects higher oil and commodity prices; looking at changes in 12m sums tends not to capture short-term swings)

The absence of real appreciation in the past undermines China’s case for reacting to the recent renminbi move by allowing the renminbi to depreciate rather than by doubling down on efforts to stimulate domestic demand. China has by far the world’s largest current account surplus. The latest World Bank report argues, I think correctly, that this surplus should persist next year even as exports slow. China will benefit more than most from the recent large fall in commodity prices. If China is unwilling to accept that its exports will slow as the global economy slows, and instead tries to offset dollar strength by weakening the renminbi against the dollar – or it tries to offset renminbi appreciation with export subsidies – everyone else will face additional competitive pressures.

China can try to support its own growth by taking a larger share of a shrinking pie, but that hardly helps the world. The G-20 isn’t just meant to bring countries together to discuss the global economy. It also needs to encourage countries to take into account the global implications of their economic policy choices. If China – which has by far the best balance of payments position of any major economy – feels like it has to direct its government policy toward maintaining export market share, efforts to rebalance the world economy will be set back.

Martin Wolf of the Financial Times has this exactly right. He writes:

Countries with large external surpluses import demand from the rest of the world. In a deep recession, this is a “beggar-my-neighbour” policy. It makes impossible the necessary combination of global rebalancing with sustained aggregate demand. John Maynard Keynes argued just this when negotiating the post-second world war order.

In short, if the world economy is to get through this crisis in reasonable shape, creditworthy surplus countries must expand domestic demand relative to potential output. How they achieve this outcome is up to them. But only in this way can the deficit countries realistically hope to avoid spending themselves into bankruptcy.

Some argue that an attempt by countries with external deficits to promote export-led growth, via exchange-rate depreciation, is a beggar-my-neighbour policy. This is the reverse of the truth. It is a policy aimed at returning to balance. The beggar-my-neighbour policy is for countries with huge external surpluses to allow a collapse in domestic demand. They are then exporting unemployment.

Over the next few months, falling oil prices will reduce the United States deficit almost no matter what. The dollar’s appreciation will only have an impact with a lag. But given Wang Qishan’s statement and the dollar’s current strength, I increasingly worry that the imbalances among the major oil-importing economies will persist even as overall trade falls.

Asia looks more keen to export its way out of trouble than to spend its way out of trouble (maybe someone should mention that supporting exports by maintaining an undervalued exchange rate is a form of hidden spending, as the government will have to pick up the costs of holding reserves it doesn’t need?). And the global slump and dollar rally have made it hard for the United States to export its way out of trouble.

Don’t get me wrong: at this point, counter-cyclical fiscal policy in the United States is essential. Absent an expansion of the US deficit, aggregate demand collapse -- further slowing the US and the world. Avoiding too much stimulus in the US in the hope that US inaction will spur more stimulus abroad would be taking a huge risk -- one I don’t want to take.

At the same time, Asian economies can not permanently rely on the US and Europe to make up for their own shortfalls of domestic demand. Trying to limit the downturn is one thing. But we should also hope to move out of this crisis with a more balanced pattern of global growth. And that means, among other things, that China ultimately needs to accept an uncomfortable real appreciation of the renminbi.

* Actually there is one way: some of the reserves that have been kept off the PBoC’s balance sheet could have come back onto its formal balance sheet. But that is a topic for later. Suffice to say that the ability to move foreign currency between the state banks and the PBoC gives China a certain amount of flexibility. It can shade its total up or down fairly easily.

** UPDATE. Logan Wright of Stone and McCarthy reports that the renminbi balance sheet of the central bank suggests that China added about $50 billion to its formal foreign exchange reserves in October while reducing its "other foreign assets" by about $25 billion (meaning the state banks were able to run down their dollar reserve requirement). That works out to a net increase in foreign assets of around $25 billion -- a level consistent with hot money outflows. Logan also reports that the central bank was a net seller of dollars on Monday, as the surprise depreciation of the central bank induced widespread expectations of further renminbi appreciation and thus short-term demand for dollars. That nuances my point that private demand for dollars doesn’t match China’s dollar inflow from its trade surplus -- it remains generally true even if it isn’t true every day or at all times.

p.s. I am on the road this week; I apologize for the sporadic posting.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store