Two Trade Variables To Watch in 2017

More on:

I suspect that few variables will tell us more about the course of the global economy, and perhaps global policy, than the evolution of Chinese and U.S. exports. Sometimes the most important indicators are simple and straightforward.

China’s exports matter for a simple reason: they could provide the basis for a true change in the narrative around China’s currency.

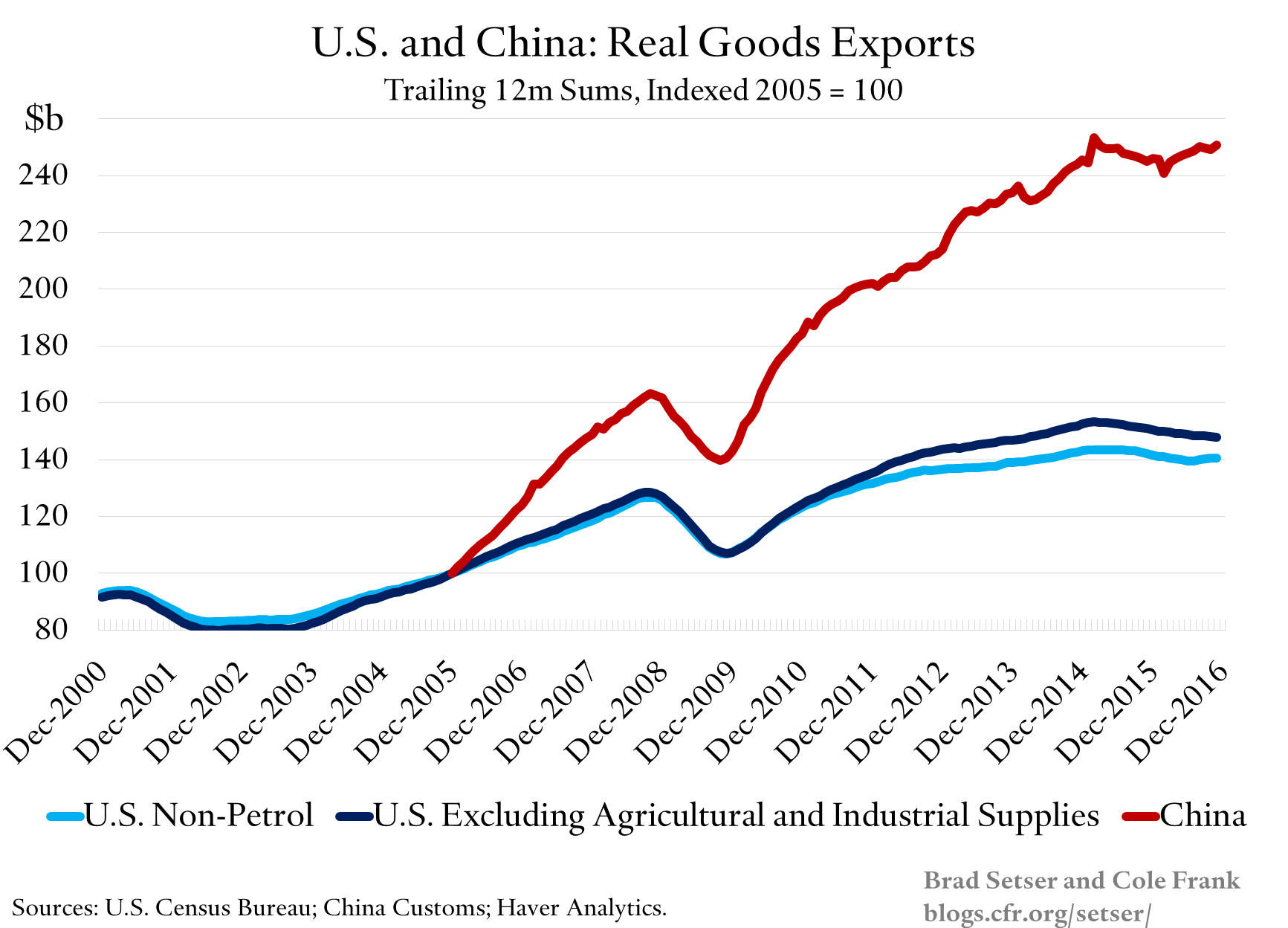

I tend to think controls can play a role in stabilizing expectations. The trade account doesn’t signal an underlying overvaluation of the yuan. China’s goods surplus is quite substantial. And China’s exports, as the chart below shows, have outperformed U.S. exports both during the period of dollar weakness (05 to 13) and in the recent period of dollar strength (chart uses a volume index, Chinese data starts in 05).

With an ongoing trade surplus, the right exchange rate is ultimately a function of the scale of outflows—and those are in part determined by expectations about what others are likely to do. If everyone wants out and can get out, it is rational to try to get out first. That is why the controls could work, especially as the nominal return on safe assets in China (still) exceeds the nominal return on safe global assets. There is also a normative judgment here too: a new China shock from a significant further depreciation against the basket and against the dollar would not help the global economy, and would add to the already considerable risks of trade conflict.

At the same time, there are likely to be limits to how tight the controls can be. It should be relatively easy for China, if it wants too, to keep its state banks from running up their foreign assets. And to keep state-run financial institutions from buying U.S. corporate bonds for their portfolio. It is far harder to control the activities of China’s export sector. Chinese exporters will be far more likely to sell their dollars and euros for yuan if the exporters believe that there is real two-way risk on the currency.

And one thing that could convince the exporters that they risk losing out if they hold their export proceeds abroad is a run of decent trade data. China’s November exports were pretty strong—China releases its own export volume data with a month lag, and the latest data shows that exports were up 8% in November. In today’s global environment that is a solid increase—though the November increase needs to be evaluated in light of October’s weak numbers. December data (out Friday) will be interesting.

And U.S. exports matter for a host of reasons.

One obvious obvious risk to the U.S. economy in 2017 is that the drag from a stronger dollar (and higher interest rates) kicks in before the expected tax cut stimulus arrives (the other risk is that the stimulus isn’t very stimulative, given that it is likely to be tilted toward high-end tax cuts)

Another obvious risk is that the collateral damage from a cycle of trade restrictions and retaliation is bigger than the market now seems to expect. Trump has emphasized policies that would lower U.S. imports (and raise the price of imports in the absence of any exchange rate moves). But cutting imports won’t reduce the trade deficit—or spur the economy—if exports fall by more.

And the available data suggests that U.S. export growth continues to be weak.

The U.S. trade deficit jumped up in November, in nominal and real terms. Exports stalled and imports jumped.

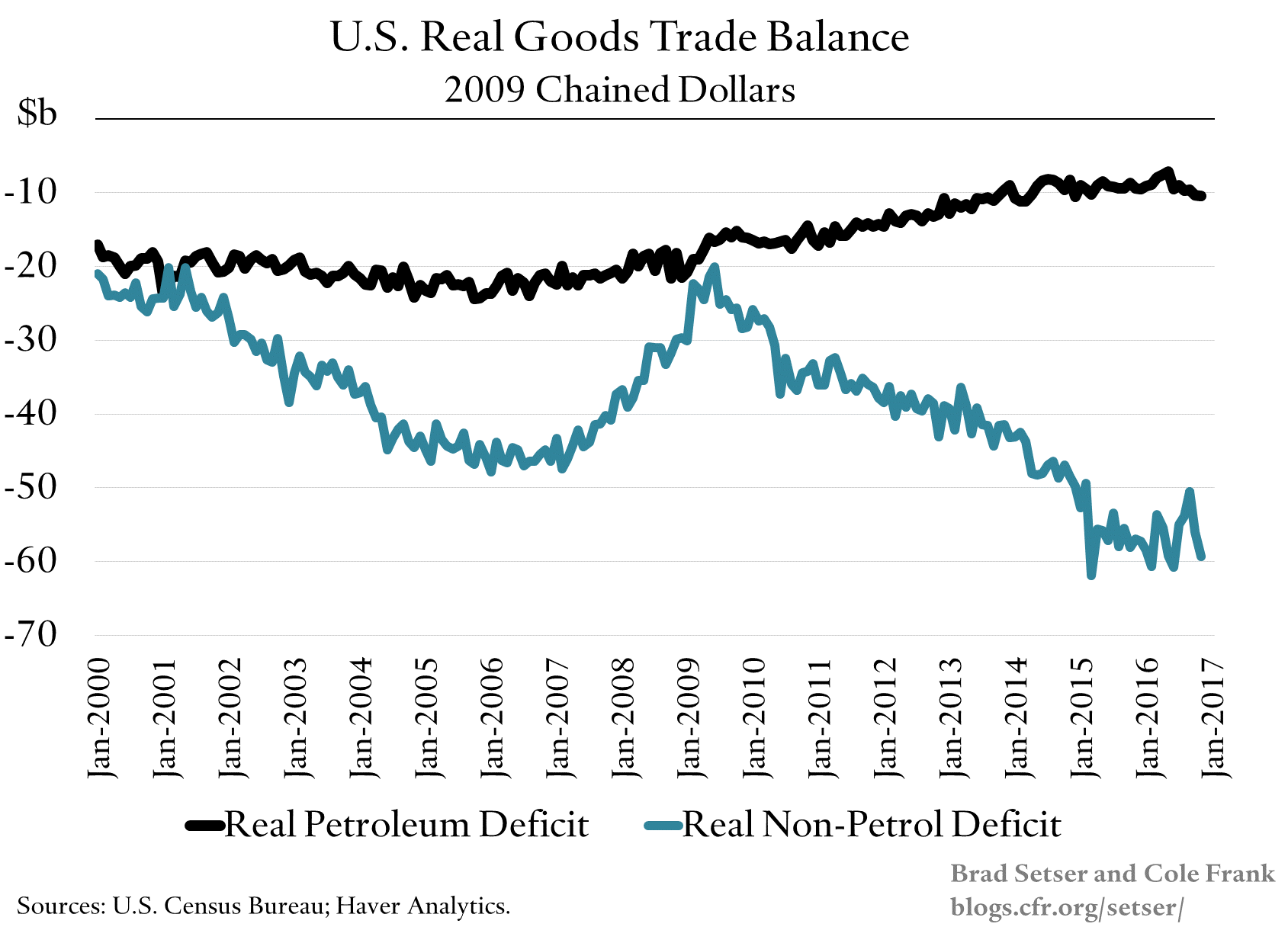

The rise in the U.S. trade deficit shouldn’t be a surprise. Oil import volumes are now rising, and oil prices are higher than they used to be. And—after a long period of no growth—non-petrol imports seem to have picked up a bit. Imports from China have been down year over year for most of the year (for 2016, nominal imports will be down about 5 percent). But in November, nominal imports from China rose 1.5% year over year. Chinese import prices are down by about as much year over year, so (rough approximation) year over year import volumes from China in November were up 3 percent. Not all that much and the monthly data bounces around, but still evidence that the factors that drove the fall in U.S. imports from China earlier this year seem to be fading.

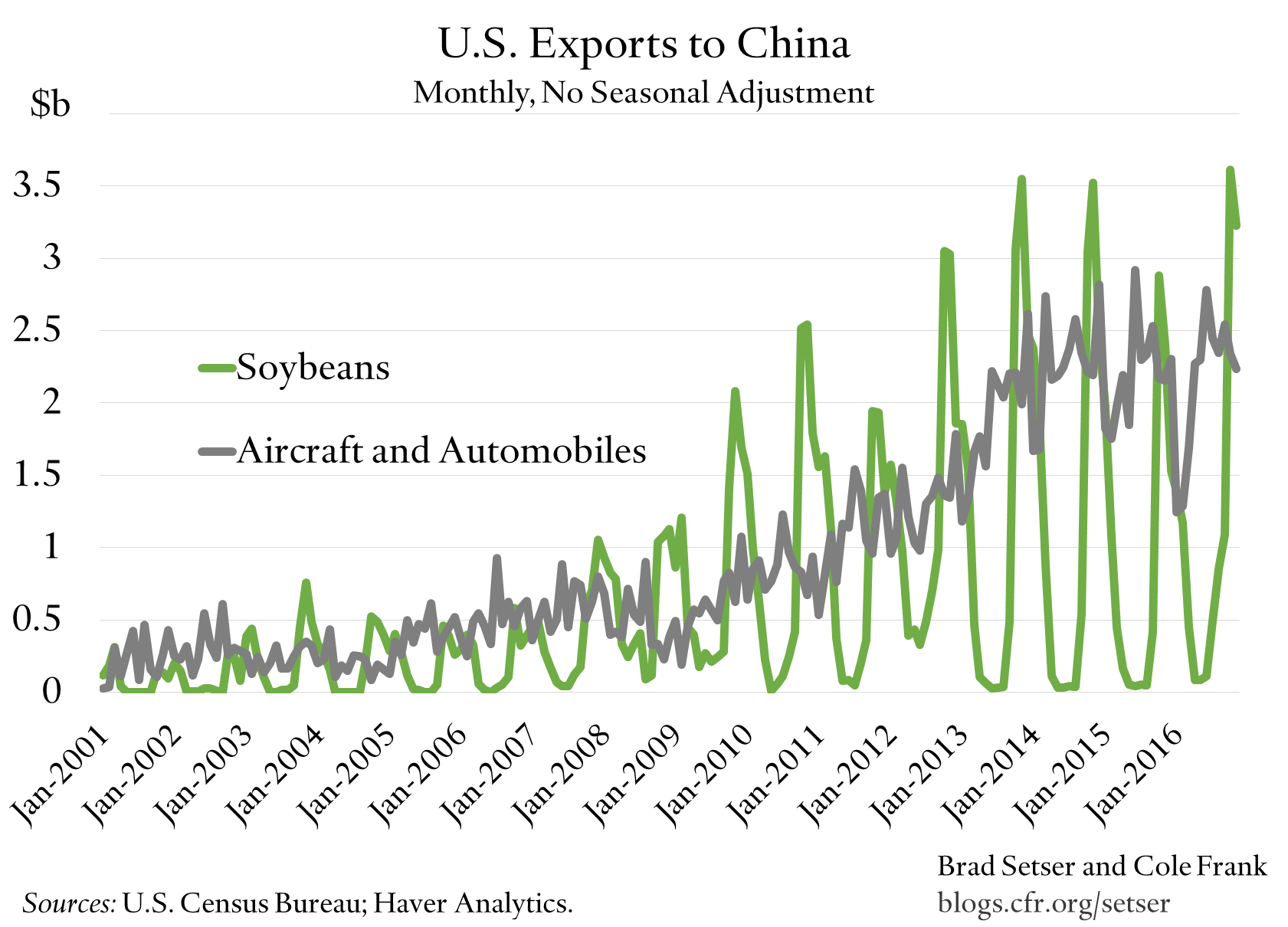

More important is the ongoing evidence that the strong dollar continues to weigh on export growth. The one-off, out-of-season surge in soybean exports this summer has faded. Post-harvest exports are running at about the level one would expect: real monthly agricultural exports have gone from $9 billion to $13 billion and now back to about $10 billion (in 2009 dollars).

One fun trade fact: in q4, the "norm" is for U.S. exports of soybeans to China to top exports of autos and aircraft to China.

Other exports remain weak. Export volumes, in real terms, for core goods (autos, capital goods and consumer goods) are still down year over year. And, as the Wall Street Journal noted in its story on the trade data, U.S. exports of capital goods exports haven’t held up well in the face of the strong dollar (and less capital expenditure in mining): "Exports of capital goods fell to their lowest level since September 2011."

That isn’t good. While the monthly numbers bounce around a bit, the trend here is actually quite clear. With the full impact of the dollar’s rise still to be felt, it is hard to be optimistic about U.S. exports. But there is an open question about just how pessimistic one should be.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store