A Web of Trust: Toward a Safe, Secure, Reliable and Open Internet

This is an excerpt of Look Who’s Watching: Surveillance, Treachery and Trust Online by Fen Osler Hampson and Eric Jardine published by CIGI Press. You can find it now on Amazon.

There is widespread recognition that the Internet also requires improved, if not new, governance arrangements to enhance its stock of eroding digital capital. The discussion is analogous to the debate political scientists are having about the breakdown of trust in democracies and the important role that institutions and their reform have to play in restoring trust and effective governance.

Proposals for reforming the governance structures of the internet vary widely and there remain deep divisions as to the direction such reforms should take. Some countries—China and Russia, to name two—would like to see governments exercise greater sovereign control over the Internet’s basic infrastructure, which today is largely managed by the not-for-profit and private sectors. But it is not just authoritarian regimes that are seeking greater control. Many democratic countries are looking to exercise greater sovereign jurisdiction over the Internet and data flows in the name of privacy, human rights, security, intellectual property rights protection, economic prosperity and competitiveness.

When it comes to developing new governance arrangements, some countries want to put the internet under the control of the United Nations. Some say that the status quo is fine and management of the internet should be left in the hands of the technical community and the private sector. Others in civil society want to strengthen multistakeholder governance arrangements so that everyone who believes they have a vested interest in the operations of the internet has a voice in how it is managed and run.

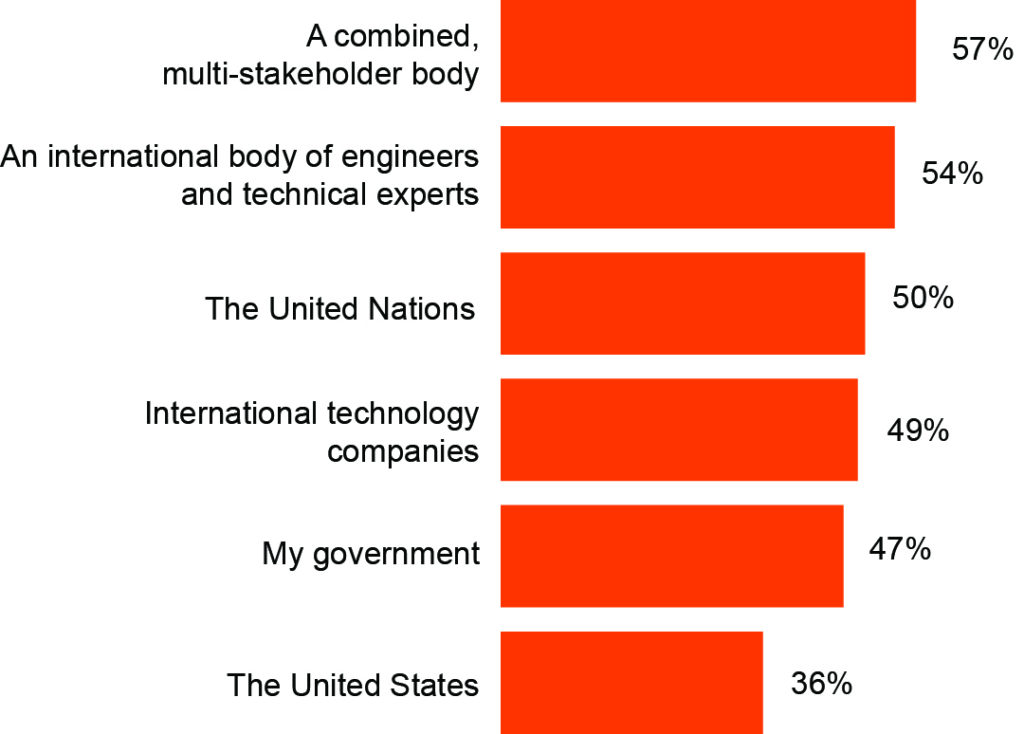

Each of these suggested ways forward runs into the idea that user trust is contingent upon the perceived inclusiveness of the governance arrangements that make decisions affecting the billions of current and future Internet users. The 2014 CIGI‑Ipsos poll is illustrative. When asked who should run the internet, a majority of people—57 percent—chose the multistakeholder option: a “combined body of technology companies, engineers, non-governmental organizations and institutions that represent the interests and will of ordinary citizens, and governments.” Fifty-four percent said they would trust an international body of engineers and technical experts, which was a little higher than the 50 percent favoring the United Nations alone. National governments and the United States had lower levels of trust, at 47 and 36 percent respectively (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1: The Public’s Preference for Multi-stakeholder Governance

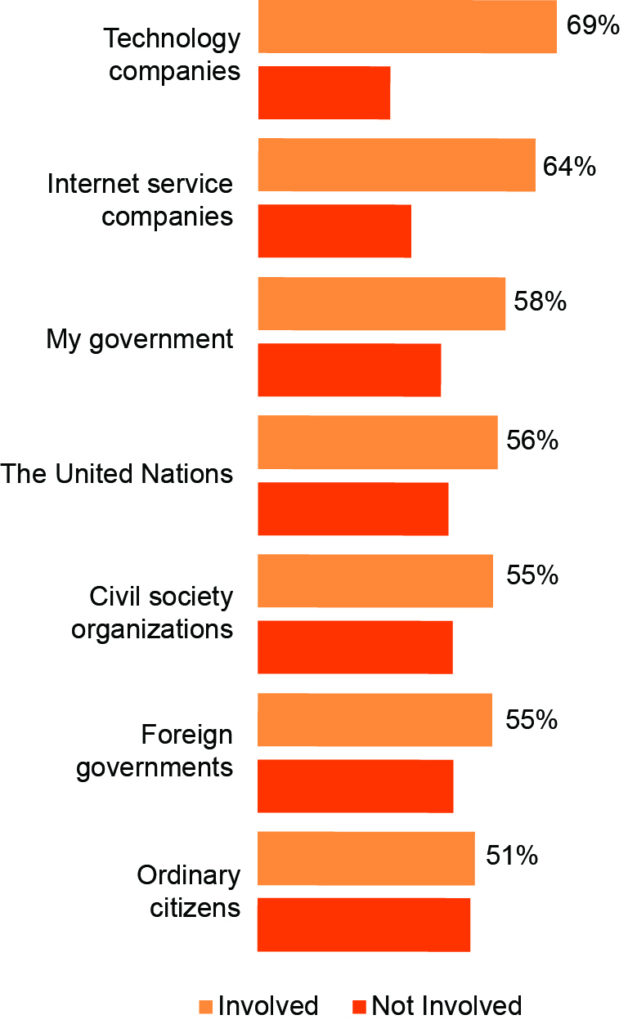

Source: Data from the CIGI-Ipsos 2014 Global Survey.This initial finding that internet users want everyone to work together is supported further by some related results from the 2016 CIGI-Ipsos poll. Asked this time about who should be involved in the development and enforcement of new rules about how user data gets used, a majority of respondents thought that every actor, ranging from technical bodies to ordinary citizens, should have a hand on the helm (Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2: Who Should Make and Enforce Rules on User Data?

Source: Data from the CIGI-Ipsos 2016 Global Survey.People also think that everyone shares the responsibility to make the internet ecosystem safe. When asked if governments should work with private companies, civil society, technologists and academics to address cyber threats, an overwhelming majority—85 percent—indicated that an all-hands-on-deck scenario is best.

The 2016 survey also highlights concerns over the privacy of user-generated data. Eighty-three percent of respondents felt that new rules were needed for how companies and governments deal with user-generated data. This finding suggests that the concerns about the coming challenges of the internet of things are likely to grow more pronounced. It also suggests that governments—and of course private companies—need to get a handle on their snooping into what users do, lest they lose the trust of people the world over.

A large majority of respondents (84 percent) are also firmly of the view that governments, private companies and users all need to be much better at implementing and enforcing existing rules to ensure that our data is protected from prying eyes. Clearly, ensuring the privacy of user data is going to be a priority for all in the coming years.

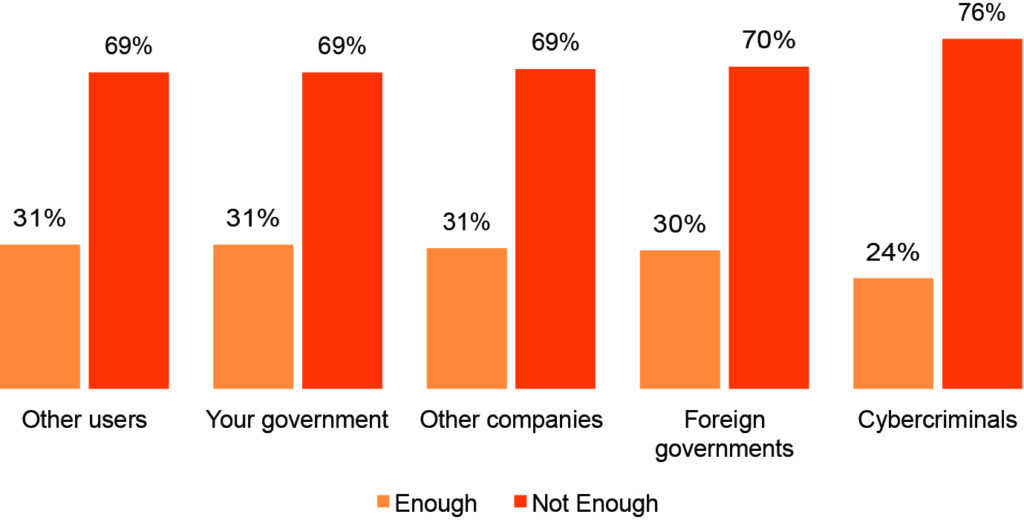

The responses also suggest that no one actor can go it alone. One clear message that internet users are trying to get across to the governments and private companies that shape so much of the internet ecosystem and its activities is that they do not do enough to protect users. The 2016 survey asked if governments and private companies were doing enough to protect ordinary users from dangers from criminals, companies and governments. The answer was a resounding no.

Users feel that companies, for example, are doing a poor job keeping them safe (Figure 9.3). Concerns over other users, the respondent’s government, foreign governments and other companies are all fairly similar, with 69 percent of people responding that the companies that they use are not doing enough. The protections provided by companies against online criminals is even more pronounced, with 76 percent of respondents disparaging corporate protections. In the wake of so many data breaches that lead to the compromise of user data, it is no wonder that people think better protections should be forthcoming.

Figure 9.3: Are Companies Doing Enough to Protect Your Data from...

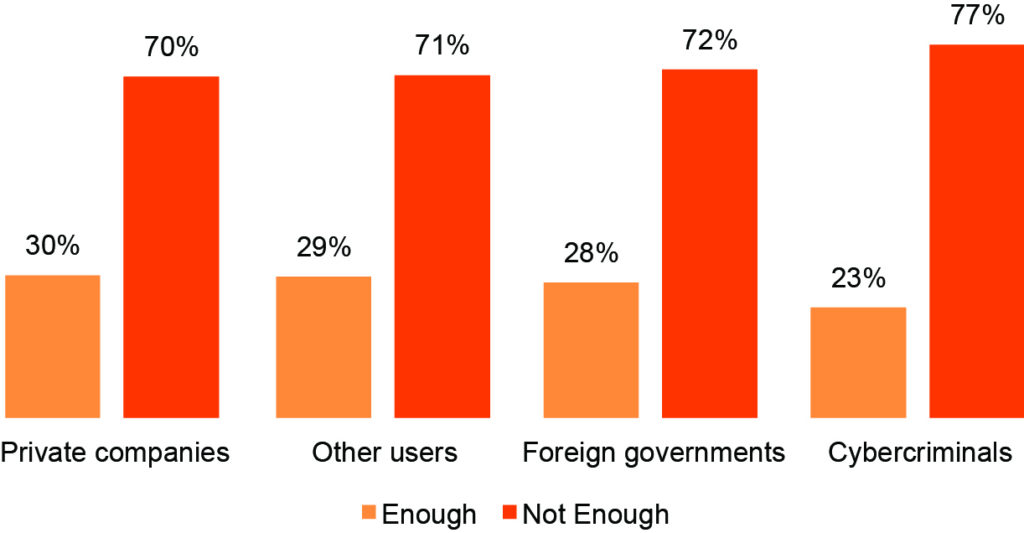

Source: Data from the CIGI-Ipsos 2016 Global Survey.Users also think that governments are falling down on the job (Figure 9.4). In fact, they are generally seen as doing even less at protecting ordinary people than are companies. When asked to pinpoint whether governments did enough to protect people from other internet users, private companies or foreign governments, around 71 percent of people indicated that the protections provided were inadequate. Users express even more dissatisfaction with governments’ efforts to protect against cybercrime than they do with private companies’ efforts. At least part of the reason why governments are more on the hook is likely because providing protection has been their historical role.

Figure 9.4: Are Governments Doing Enough to Protect Your Data from...

Source: Data from the CIGI-Ipsos 2016 Global Survey.One of the conundrums when trying to restore trust as regards the security of operating systems or platforms is that such efforts, by necessity of design, may lead to further intrusions on individual privacy. For example, in the 2015 rollout of the Windows 10 operating system, Microsoft baked into the new system much higher levels of security (which users clearly want). Confronted with ever-evolving cybercrime, Microsoft rejected their old way of doing things and now pushes out security updates on a regular basis that patch vulnerabilities to help keep users safe. As the Windows team blogged, “Windows 10 has more built-in security protections to help safeguard you against viruses, phishing, and malware, it’s the most secure Windows ever. New features are now delivered through automatic updates, helping you to stay current and your system to feel fresh, so you’re free to do.”

These additional security features also come with a largely unavoidable loss of user privacy. Microsoft has to access, by default, a pile of information, including location data, usage of applications and browser history in order to monitor security breaches—a compromise that many users are apparently prepared to accept.

Online Store

Online Store