Will the world’s macroeconomic imbalances soon reduce to China’s surplus and offsetting deficits in the US and Europe?

More on:

The recent fall in oil prices, if sustained, should bring down the external surplus of the oil exporters. $80 a barrel is well above the average price of oil for most of the 1990s – or for that matter 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2006. But the oil exporters are spending and investing (and thus importing) a lot more as well. By next year, a $80 a barrel oil price won’t generate a big surplus to be managed by the oil exporters central banks and sovereign funds.

The yen has long looked very weak relative to the euro. But that too has changed. The yen’s recent rally – if sustained – should, over time, work to reduce Japan’s surplus (though the fall in commodity prices works the other way).

That more or less leaves China’s surplus – and the offsetting deficits in the US and Europe. There is good reason to think China’s export growth should slow over the next year. Neither the US nor the European economy looks likely to expand much in the near future. The dollar’s recent rally has led to a much more significant broad appreciation of the RMB than the RMB’s appreciation against the dollar ever did. Back then, the RMB never appreciated enough against the dollar to make up for the dollar’s fall. This broad appreciation should make it more difficult for China to offset weak growth in its exports to the US with strong growth elsewhere.

But there isn’t much evidence of a slowdown in China’s exports yet. Nominal export growth is chugging along at about 20% y/y – which implies the China is on track to export about $250 billion more this year than last year. That has kept China’s overall trade surplus more or less constant even as China’s (commodity) import bill soared in the first few quarters. China’s q3 2008 trade surplus ($83.3b) was about $10b more than its trade surplus in q3 2007 ($73.2b). Yes, the pace of real export growth has slowed. But at something like 10%, China’s real export growth is still comparable if not stronger than US export growth. Net exports contributed positively to China’s GDP growth in q1. The World Bank’s economists believe that they will contribute to q2 GDP growth – and I would be shocked if they don’t contribute positively to China’s GDP growth in q3 as well.

Looking forward, export growth should slow – in both nominal and real terms. But nominal import growth should slow as well, as China’s commodity import bill falls. I don’t yet see much evidence that China’s overall surplus will fall. And lest we forget, China has by far the largest surplus of all the major economies. The great boom in China’s exports that started in 2002 or 2003 looks – at least to me – to be continuing.

China is an outlier when it comes to reserve growth as well. In q3, many emerging economies saw their reserves fall. Not China. It – along with Saudi Arabia – likely will keep global reserve growth from turning negative. China’s stated reserves increased by $96.8b in q3, bringing total reserves to just over $1.9 trillion.

Both numbers are deceptive.

China’s state banks hold about $200 billion of foreign exchange as part of their mandatory reserves requirement, foreign exchange that – per China stakes – is on deposit at the PBoC and is managed by the SAFE (See Xu Yisheng of China Stakes). That implies that SAFE already manages an external portfolio of $2.1 trillion – far more than anyone else.

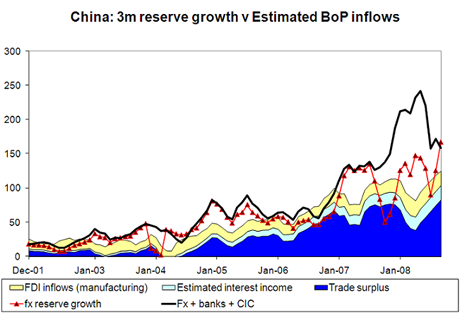

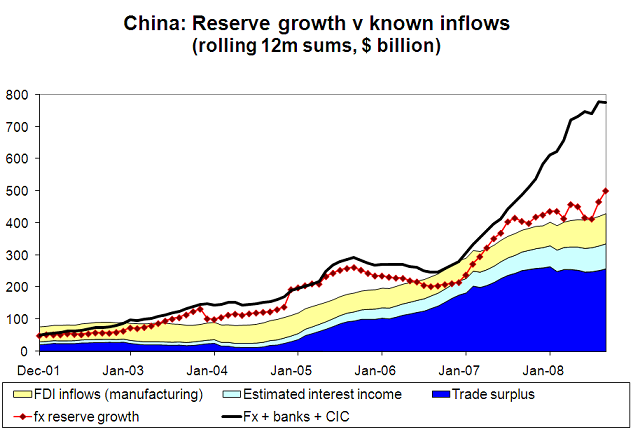

And the $96.8b in headline increase understates the “true” increase in China’s reserves. China has some euros and pounds – and those euros and pounds fell in value. If China has about 67% of its portfolio in dollars (and if it has a fairly low yen share), the falling dollar value of China’s euros and pounds subtracted about $70b from China’s reserve growth in q3 -- implying that China actually bought about $165b in the fx market to keep its currency from appreciating.

That is a bit less than in q1 and q2 once adjustments are made for funds shifted to the CIC – but it is still a large number.

Now in the past the growth in China’s stated reserves has been misleading, as foreign exchange was shifted to the state banks in ways that held down overall reserve growth. There is at least a possibility that the opposite was true in q3 – and that China’s true foreign asset growth was less than $165b. In July and August, Logan Wright reports that PBoC’s other foreign assets – a line item that seems to correspond with the dollar reserves of the state banks held to meet a portion of China’s reserve requirement -- fell by $7.5b. That brings the total increase in q3 below $60b.

But it doesn’t answer one key puzzle: almost all the valuation losses came in August (an estimated $40b) – which implies that China’s “true” August reserve growth was $80b. Frankly, that is a bit suspicious.

Maybe China’s state banks – contrary to what China Stakes reports – reduced their dollar reserves when the reserve requirement was reduced? Or maybe they otherwise reduced their foreign holdings, basically paying back funds that they had previously borrowed from the PBoC to invest abroad? Until the details of the foreign currency balance sheet of China’s state banks are released we won’t know.

But we do know that China’s trade surplus remains very large – and that it is still adding to its reserves at a fast clip. Over the last 12 months (q3 2007 to q3 2008) I estimate that China’s government added roughly $700 billion to its foreign assets (counting the increase in the CIC’s foreign assets as well as the dollar reserve requirement managed by the PBoC) to keep its exchange rate from appreciating.

And while there is good reason to think that the growth in Russian and GCC foreign assets is poised sharply, evidence that China’s surplus is about to fall remains, for now, rather thin.

No one paid much attention – in part because the IMF writes in code – but the chapter of the IMF’s WEO that examined the current account balances of emerging economies documented both that China’s real exchange rate has been unusually weak and that China’s external surplus has been unusually large. It doesn’t take much of a leap to think that those two facts are related.

This doesn’t just matter to the US and Europe either. China’s exports to India have absolutely soared over the past two years – and I suspect that the combination of competition from China in export markets and rising commodity prices helps to explain why other emerging Asian economies weren’t able to sustain their appreciation against the dollar for long.

UPDATE: After looking at the analysis of Michael Pettis (which draws on the work of Logan Wright), I realized that something was off in my valuation adjustment function. It turns out that I had end-July exchange rate data in the end-August file. As a result, I initially attributed all the valuation changes to September when most were in August. My valuation-adjusted reserve growth now is $43b for July, $79b for August and $40b for September. The graphs are consequently a tiny bit off -- I’ll update them later today.

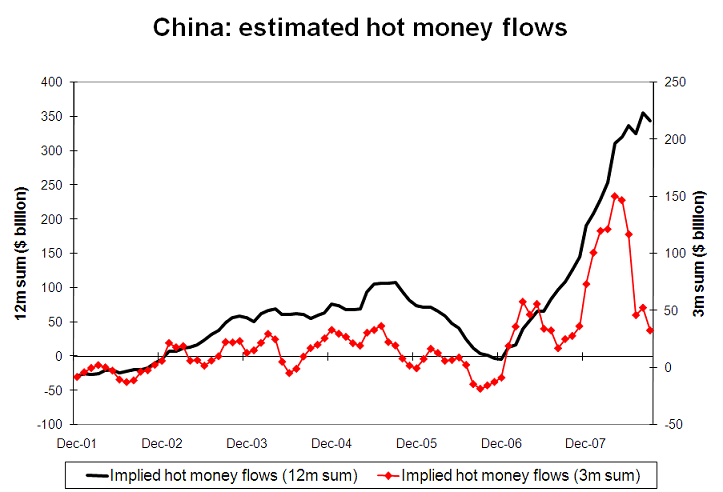

The graphs have been updated -- here is a bonus one showing estimated hot money inflows.

My analysis -- which doesn’t incorporate all potential flows between the PBoC and the state banks, so it could be incomplete -- suggests a large fall off in hot money flows. However, on a rolling 3m basis, money still seems to be coming in (or at least not leaving).

More on:

Online Store

Online Store