Defending Ukraine in the Absence of NATO Security Guarantees

Overview

A cease-fire deal with Russia will not ensure Ukraine’s long-term security. CFR’s Paul Stares and the Brookings Institution’s Michael O’Hanlon argue for a multilayered defense system that could prevent another invasion while being financially sustainable for Ukraine’s allies.

BY

- Paul B. StaresGeneral John W. Vessey Senior Fellow for Conflict Prevention and Director of the Center for Preventive Action

- Michael O'HanlonSenior Fellow and Director of Research, Brookings Institution Foreign Policy Program

This report is part of the Council Special Initiative on Securing Ukraine’s Future.

Executive Summary

Ending the Russia-Ukraine war will be difficult and likely require a broader range of incentives (positive and negative) than the world has yet presented to bring both parties to the negotiating table. Even in the event that a cease-fire or armistice agreement is reached, the question of its durability remains. Ukraine will need to determine how to deter Russia from using any period of calm as an opportunity to rearm, wait for the world to lower its collective guard, and then attack again. In consequence, any strategy should be centered on building a robust Ukrainian military with strong deterrent capabilities, and planning for how that postwar military should be shaped, sized, and budgeted needs to begin now.

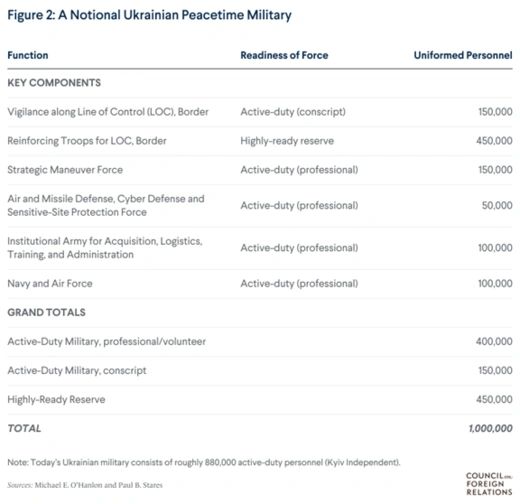

Ukrainian officials have consistently opposed reaching a cease-fire agreement with Russia unless they also receive clear NATO security guarantees. Anything less, they believe, will leave the country exposed to future Russian aggression. However, there is another path, and a more plausible one: Ukraine can defend itself effectively if attacked in the aftermath of a cease-fire agreement by creating a multilayered territorial defense system for the roughly 80 percent of its pre-2014 territory that it still controls. This step would comprise a hardened outer defense perimeter, a strategic rapid-response force to respond to serious threats, and enhanced protection for major population centers and critical infrastructure. A defense system configured this way would require a substantial military force—some 550,000 on active duty (drawing on professional and conscripted personnel) and another 450,000 in ready reserve. Given Ukraine’s demographic outlook, creating such a force will be difficult, but not impossible.

Arming, training, and supporting the force will require substantial foreign assistance for the foreseeable future. Ukraine will need to spend between $20 billion and $40 billion per year, comparable to the defense budgets of Israel and South Korea. This estimate is much lower than current wartime expenditures, while also being cheaper for foreign benefactors to support compared to what they would likely have to pay to defend against Russia in the event Ukraine were defeated.

Planning for the defense of Ukraine in the absence of NATO security guarantees should begin now regardless of the timing of cease-fire negotiations. Moreover, to the extent possible, the terms and provisions of a cease-fire agreement should go beyond simply ending the war, and instead advance Ukraine’s future security. They could include measures for each side and/or international personnel under UN or Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) auspices to monitor cease-fire lines; they could also include limitations on force buildups near that armistice line. Cease-fire terms could further include some type of additional modest foreign military presence to train Ukrainians and act as tripwires against a resumption of conflict. Ukraine should not be left without outside security commitments or assistance, but in recognizing the reality that NATO membership is unlikely, Ukraine should aim for robust self-defense capability regardless of the broader region security architecture.

Introduction

Negotiating an end to the fighting in Ukraine represents one of the top foreign policy priorities of the second Donald Trump administration.1 The reasons are compelling. The conflict has become by far the deadliest and most destructive conflict in Europe since the end of World War II. Hundreds of thousands of people on both sides have been killed or wounded, and many of Ukraine’s cities and much of its infrastructure have been destroyed.2 Millions have also been displaced or chosen to leave Ukraine.3 Global food and energy markets, moreover, continue to be disrupted, especially for those in the Global South. And, arguably most concerning of all, while the fighting has settled into a deadly impasse, the risk that it could suddenly escalate—potentially leading to a direct clash between members of NATO and Russia—persists.

How the Trump administration will pursue a cease-fire in Ukraine remains to be seen. The obstacles to a negotiated settlement are formidable. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has indicated his willingness to discuss a cease-fire and even signaled that the return of territory currently occupied by Russia is not a precondition, but he has insisted that NATO extend security guarantees to deter any future Russian aggression.4 Ukraine joining NATO, however, is anathema to Russian President Vladimir Putin and probably unrealistic in any case: President Trump has questioned Ukraine’s potential accession to NATO and several other members of the alliance are lukewarm at best.5

Other kinds of security guarantees for Ukraine are conceivable, but if they involve the permanent deployment of foreign combat-ready forces on Ukrainian soil, especially within striking range of Russia, they too could be a deal-breaker for Putin.6 Some observers have consequently concluded that the only workable solution is for Ukraine to become a neutral, nonaligned state, free of foreign forces, much like Austria and Finland during the Cold War. Such an outcome would hardly be appealing to Ukraine. This status, after all, was more or less its posture after gaining independence in 1991, which Russia then violated in 2014.7 Putin has also shown no hesitation in breaking various cease-fire agreements, notably the Minsk agreements, signed in 2014 and 2015.8

While acknowledging the difficulties of finding an outcome fully satisfactory to all parties, nevertheless, the parameters of an acceptable deal exist. To be sure, Putin could now believe he has (modest) military momentum and more strategic depth and resources than Ukraine. Indeed, as Trump has indicated, much greater economic pressure against Russia could be needed as part of any strategy to end the fighting. However, an armistice could still become possible over the coming months, and it is safe to assume further that , any deal would involve an initial cease-fire agreement that more or less freezes the current front lines while deferring the resolution of Ukraine’s official territorial boundaries to a later date. Lands currently occupied by force would not be internationally recognized until all parties freely and willingly consent to a formal and final settlement. Ukraine would retain the right, as any sovereign nation, to choose its own security arrangements and political associations, but the question of it joining NATO would be deferred to a later date. Thus, while Ukraine would not become a neutral state in the formal meaning of the term, it would observe non-bloc status—a Russian demand and something it was evidently prepared to accept during cease-fire negotiations in early 2022.9 In lieu of NATO security guarantees in the foreseeable future, Ukraine would deter potential future aggression from Russia through a multilayered territorial defense system that Moscow would have little or no confidence in overcoming, certainly at an acceptable cost.10

Many Ukrainians will doubtless find that arrangement unsatisfactory and certainly inferior to putatively ironclad NATO security guarantees. Yet there are other reasons, besides the present impracticality of the idea, to focus less on NATO membership. Such guarantees are hardly a panacea and always come with the risk that they will not be honored when needed.11 NATO spent decades during the Cold War building forward defenses, as well as elaborate nuclear weapons doctrines and operational procedures, because the simple existence of Article 5 was never seen as ensuring peace. In short, there is nothing guaranteed about security guarantees.

A multilayered defense system would, however, provide credible protection for Ukraine so that it can survive and thrive as an independent sovereign state for the foreseeable future. Crucially, the necessary elements of such a system cannot be left to the aftermath of a cease-fire agreement. Planning for it needs to begin now so that its certain prospect can allow Ukraine to negotiate from a position of strength and confidence about its future security. Where possible, moreover, the terms of a cease-fire agreement, and certainly a larger settlement of the conflict, should be deliberately designed to enhance Ukraine’s future security, not just end the bloodshed.

Ukraine’s Security Challenges After a Cease-fire

Ukraine faces a forbidding set of security challenges in the aftermath of any potential cease-fire agreement that freezes the fighting along current battle lines. Besides resisting potential efforts to isolate and delegitimize Ukraine politically and undermine it economically, the main security imperatives will be to defend its new land perimeter from future ground and air attack, its cities and critical infrastructure from aerial bombardment (as well as cyber interference and sabotage), and its vital maritime commercial routes through the Black Sea from hindrance and closure.

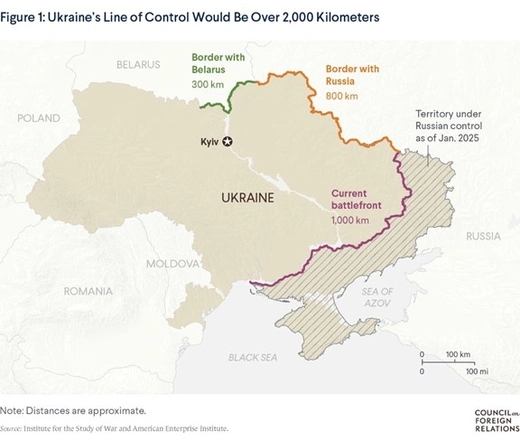

Looking at the land defense challenge first, Ukraine would need to defend the agreed Line of Control (LOC) between Ukrainian and Russian forces. If it follows the current battlefront in eastern and southern Ukraine, the LOC would be approximately one thousand kilometers in length (just over six hundred miles), running from the vicinity of Crimea in the south all the way to the border with Russia in the northeast. This is slightly longer than the western front of World War I, and about four times the length of the inter-Korean border, or demilitarized zone (DMZ), today. In addition, Ukraine would have to defend other sections of its border with Russia and arguably Belarus, given the Russian army’s use of the latter’s territory to stage attacks against Kyiv in the beginning of the invasion in 2022. This would add around 1,000 kilometers to the defense perimeter (approximately 800 kilometers from where the current front intersects the Ukraine-Russia border to where it meets Belarus and approximately 300 kilometers of the Ukraine-Belarus border fronting the approaches to Kyiv)—for a total of roughly 2,100 kilometers (1,300 miles). (See figure 1.) By comparison, NATO’s central front during the Cold War—in effect the inter-German border—was approximately 1,400 kilometers (870 miles) in length.

The boundaries of this territorial defense perimeter would encompass slightly more than 80 percent of pre-2014 Ukraine and would include eight of Ukraine’s most populated cities: Kyiv, Kharkiv, Dnipro, Odesa, Zaporizhzhia, Lviv, Kryvyi Rih, and Mykolaiv. Those cities alone contain 8.94 million people, nearly a quarter of Ukraine’s wartime population.12 This area of Ukraine also accounts for a significant amount of Ukraine’s prewar economic output and can support continued economic activity in the future. While upwards of ten million Ukrainians have been displaced since the 2022 invasion, either internally or abroad, major efforts and incentives will be needed to induce them to return home or start life in a different part of unoccupied Ukraine.13

Ensuring that Ukraine could freely use its seaports following a cease-fire and thus import and export goods through the Black Sea represents another major defense requirement. Since the invasion, Ukraine has lost control of Mariupol while Mykolaiv has been rendered inoperable due to wartime damage. Three other ports—Chornomorsk, Odesa, and Pivdennyi ––are currently operating at partial capacity.14 Fortunately, global grain markets have been performing well for most of the war, and Ukraine has managed to reestablish much of its export capacity through sea lanes along the western coast of the Black Sea.15 Finally, Ukraine would need to defend its principal sources of energy and related critical infrastructure. Currently, it is heavily dependent on nuclear power production as well as large hydrocarbon plants. Ukraine will need to protect those while further diversifying its energy production.16

A Multilayered Defense System for Ukraine

Ukraine’s ability to defend itself in the face of those demanding security challenges will hinge on several factors, notably the level of indigenous defensive capabilities available to Ukraine for the foreseeable future (not least the size of its draftable population and industrial base), the amount of assistance—economic, technological, and military—external benefactors are prepared or permitted to provide, and the extent to which sanctions designed to restrict Russia’s offensive military capabilities continue to be applied, if not extended. Each factor will be important in a multilayered defense system for Ukraine, where each layer or tier is mutually complementary.

First, Ukraine will need to transform its security forces from their current wartime size, composition, and posture to something smaller and more affordable. But to ensure Ukraine’s safety along the way, this process needs to be carried out carefully: Ukrainian armed forces need an evolution, rather than a revolution. Fortunately, most components for a multilayered defense system—a forward-defense posture backed up by a strategic reserve of maneuver forces, complemented by air and missile defenses, and with sea and cyber defense capabilities—already exists and therefore provides much of the template for what Ukraine should do in the first years after a cease-fire. As such, the multilayered approach will be most relevant for the late 2020s and perhaps the early 2030s; new ideas and new technologies could allow (or require) a different approach over the long term.

Of course, it will be up to Ukrainians to make those decisions in the end. But Western friends of Ukraine, in addition to contributing to the debate with their ideas and expertise, need some broad independent sense of what kind of Ukrainian military they would consider adequate and feasible, since they will be expected to help fund and equip it, at the very least. The decisions are first and foremost for Ukrainians but should derive from a larger conversation.

Tier 1: A Hardened Outer Defense Perimeter

Ukraine has already demonstrated a remarkable capacity to withstand attacks by Russia’s numerically superior forces along a defensive perimeter that will likely approximate the length of the post–cease-fire LOC. This has been accomplished, moreover, under wartime conditions, whereas a cease-fire will provide an uninterrupted opportunity to reinforce and extend current defenses and build new or better ones where needed. Thus, while it is true that a cease-fire or more substantive armistice agreement would allow Russia to rest and refit its forces to renew offensive operations at some point in the future, Ukraine would also have the opportunity to make its defenses more formidable and effective—and it already has a battle-tested, basic concept for how to do so.

Ukraine’s current defensive lines can be bolstered in a variety of ways to create an intimidating set of barriers. Such defenses could include the use of deep and dense minefields, anti-tank barriers (dragon’s teeth obstacles, berms, ditches, etc.), heavily protected fortifications and trenches backed by drones, and precision-strike artillery and missile systems.17 Indeed, most of those capabilities are already in place along the one thousand kilometer front lines.

Such defensive preparations by Russia doomed the much-anticipated Ukraine counteroffensive in the summer of 2023.18 Ukraine has since gradually built similar fortifications, after avoiding such actions initially out of concern that they would appear to concede the territory that Russia has seized.19 However unpalatable such decisions could have been politically and psychologically for Ukrainian leadership and the Ukrainian people, they were prudent and indeed necessary. In consequence, offensive operations have been very difficult for either side during most of the last two years.20

A reinforced defensive perimeter would be manned by a standing holding force meant to repel a Russian attack and buy time if needed for a strategic reserve force to respond and neutralize any serious threats or breach of the forward defensive lines. How large this holding force would need to be is difficult to calculate. There is no generally accepted force-to-space ratio to defend a given length of territory—indeed, the notion that there can be one has been thoroughly debunked.21 Military analysts often assert that successful offensive operations require a three-to-one advantage, at least at the point of attack, suggesting that Ukraine would need to maintain a force capable of nullifying any larger disparity. Such a calculation, however, ignores the many qualitative variables that determine combat effectiveness for either the defender or attacker, an observation that has been borne out by numerous historical cases. Moreover, new technologies, to include the next generations of unmanned systems, could change military realities and offense-defense balances in the future.

Nonetheless, a reasonable estimate of what Ukraine would need can be derived from recent combat experience, which has already demonstrated the integration of old-fashioned techniques of trench warfare—artillery, fortifications, and tactical movements of dismounted infantry—with satellite-enabled and artificial intelligence–assisted networks of sensors and unmanned attack drones.

On one side, Russia has managed to prevent any serious Ukrainian counteroffensive since 2023 with a force of approximately 500,000 troops deployed along a 1,000-kilometer front (a ratio of 500 troops to every kilometer), helped in places by a system of fortifications including minefields, dragon’s teeth, and other barriers that its engineers put in place after the disastrous Russian military offensives of 2022. However, that total has both defensive and offensive capabilities and purposes.

On the other side, Ukraine has maintained around 300,000 troops near the front, focused on defensive operations since 2024.22 That Ukrainian force has not quite been up to the task of maintaining a robust defense; Russia gained more than 1,000 square miles of territory (almost 0.5 percent of pre-2014 Ukraine) over the course of 2024.23 But the Ukrainian effort has succeeded in making Russian gains slow and immensely costly. Together, those two examples suggest that about 400,000 troops would be needed to defend the whole front line with high confidence, or about 400 soldiers per kilometer.24

This calculation, however, does not include defense of Ukraine’s northern borders with Russia and Belarus. Much, if not all, of those borders should be protected: Ukraine’s defensive preparations should resemble the Korean DMZ or the inter-German Cold War border rather than the French Maginot Line that Germany circumvented in 1940. If Ukraine decides that it is necessary to defend only the border with Russia, at least in peacetime, then a total wartime force of around 600,000 Ukrainian soldiers would be necessary to defend the entire defensive perimeter. If Ukraine feels the need to defend the border with Belarus as well, those numbers could have to increase by roughly another third.

A large proportion of the necessary forward-defense forces could be mobilized and deployed to defensive positions on warning of attack. The experience of 2021–22 suggests that any large-scale Russian buildup would be noticed well in advance of an attack. Indeed, U.S. intelligence knew something major was afoot once Russian forces exceeded about 100,000 (they would later approach 200,000 on the eve of the all-out invasion).25 Thus, even if a robust front-line defense were to require around 600,000 troops, it could suffice to have one-fourth that number in or near position under normal circumstances, with the rest available over a period of roughly one to two months—the time horizon that appears needed for a major Russian mobilization. Whether those forces would need to be active-duty or part of a high-readiness reserve is another matter.

Combining those considerations, in order to man its front-line positions, Ukraine would likely require an active-duty force of about 150,000 soldiers, plus an additional 450,000 who could be activated and deployed within one to two months. Those forces should also have adequate stockpiles of weaponry. For example, given Ukraine’s typical artillery usage rates of several thousand rounds a day, it would be prudent to be prepared for months of similar future fighting before additional supplies could arrive in large amounts from foreign or domestic sources. That means several hundred thousand rounds should be stockpiled, many near the front lines, in advance.

It is possible that a minimal standing force of 150,000 could be further reduced by developing multiple layers of fortifications and ready fleets of reconnaissance and attack drones. That said, Ukraine should err on the side of caution. Drones are already heavily relied on in the current fighting, and overdependence could create vulnerabilities if they wind up susceptible to future advances in cyberattacks, electronic warfare, or directed-energy weapons, among other possibilities.

This force would be optimized for defensive operations with the provision of mobile artillery, anti-tank, and air-defense systems; tactical, strike, and counter-drone systems, as well as deep-strike missile systems to attack rear-echelon forces; and logistical, transportation hubs. All would require reliable and timely battlefield surveillance and command-and-control systems. Whether Ukraine would need to build up an air force specifically to provide air cover and ground support for the defense force is debatable, given the cost of maintaining that capability and the severity of the operational challenges—as well as the newfound ability of drones to play many of the roles more traditionally performed by manned aircraft.26

Besides its land-defense component, Ukraine would also need to prevent potential Russian efforts to deny its use of the Black Sea for commercial purposes, not to mention the use of amphibious forces in support of land operations. To date, Ukraine has done remarkably well at preventing Russia’s Black Sea Fleet and air forces from interdicting its commercial shipping. Besides hugging close to the waterways and coastline of neighboring NATO countries to dissuade Russian attacks, Ukraine’s own naval forces have sunk a large proportion of Russia’s naval forces and forced them east of the Crimean Peninsula. There is no reason to question its continued ability to do so with investments in coastal missile batteries and maritime and aerial drones, backed up by a robust surveillance and command-and-control system.

Tier 2: A Strategic Rapid-Response Force

While Ukraine will seek to prevent any serious breach of its outer defensive perimeter, it should also make provisions to respond rapidly in the event a significant Russian penetration occurs or seems imminent. Russia could carry out a clever ruse that leads Ukraine to let its guard down in a given sector—or even find a way to infect Ukrainian soldiers through some kind of biological attack or resort to the limited tactical use of nuclear weapons (though such an act would be appalling to world global opinion, even in a sparsely populated region). Whatever the scenario, Ukraine will not want to base its entire security strategy on its forward defenses; a strategic reserve with maneuver capability will be vital should the front lines be breached.

A suitable rapid-response force should have the capability to operate relatively autonomously and quickly move several hundred miles after mobilizing and marshalling its personnel and equipment. How large this force should be depends largely on the size and capabilities of the opposing forces. Again, recent history provides some pointers.

Russia’s mobilizations in the current war have tended to include up to 300,000 personnel or so in any one period. But those mobilizations have largely been designed to grow the overall force in Ukraine to 500,000 soldiers and then keep it at that level, despite ongoing losses. If Russia also desired a breakthrough force with greater mobility, logistical sustainability, and firepower than defensive units, it could additionally aim to field 150,000 crack troops—a force big enough that, if it did break through Ukrainian lines, would have a good chance of encircling a substantial fraction of the Ukrainian military and forcing its surrender, thereby turning a tactical success into something of strategic consequence.27

As noted, a well-equipped and well-trained military force does not always need numerical parity with aggressors to defend territory, given its advantages in familiar terrain and prepared fortifications. Nevertheless, attackers have been known to break through without a significantly larger force.28 Rough parity seems a more reasonable standard to maintain for deterrence purposes and, if deterrence fails, to have a good chance of defeating any invading army. That reasoning suggests that, in addition to the 150,000 forward-positioned front-line troops and the additional 450,000 backup force capable of being mobilized rapidly on receipt of warning, Ukraine also will need a mobile strategic reserve of around 150,000 ready troops to handle any serious breakthrough. (See figure 2.) Adding up the numbers, Ukraine needs an active-duty army of at least 300,000 soldiers, as well as another 450,000 soldiers, either in a very ready reserve or the active-duty forces, that could rapidly mobilize, move out, and reinforce.

Indeed, Ukraine will also need three additional types of military capabilities: an institutional army, capabilities for air and missile defense and site security throughout the country, and limited air and naval forces. Thus, as figure 1 indicates, a postwar Ukrainian military should consist of 1,000,000 total personnel—some 550,000 in active-duty forces (most of them professional, some conscript) and another 450,000 as a highly ready reserve. Adjusted for population size, these active-duty figures are slightly less than those for Israel and greater than those for South Korea, two countries that have somewhat related security challenges given the hostility of their neighbors. This Ukrainian reserve force is much smaller relative to population size than that of the other two countries.29

For Ukraine to maintain such a force after a cease-fire will not be easy given its demographic outlook.30 Due to a post-Soviet baby bust, no more than two hundred thousand young Ukrainian men are coming of age for conscription each year. Some of those are now abroad or in Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine. Kyiv would do well to enlist even half that total number, especially given other practical constraints such as health issues and other exemptions. That is why the proposed conscript force could be limited to about 150,000 total troops, something Ukraine could probably muster with mandatory service terms of two-to-three years (depending, among other things, on whether some women were drafted as well).

In summary, professional military forces would maintain air, missile, and coastal defenses; constitute the rapid-reaction force or strategic reserve; and operate deep-strike, counteroffensive capabilities against Russia proper. Additionally, they would maintain peacetime intelligence gathering, special forces, and early-warning monitoring, as well as security for top officials and sensitive sites. They would also constitute the institutional army, charged with the acquisition of weaponry, logistics, administration, recruiting, and training. Ukraine’s modest but crucially important naval and air forces would consist of professional volunteers as well, normally with longer tours of service. Again, a modest-sized active force with conscripts would maintain continuous forward positions along the LOC and the northern border. A larger reserve force (the 450,000 later-mobilizing troops) built on the Israeli or South Korean models would drill annually and stand ready to mobilize quickly in a crisis. Service in the latter could be either obligatory or voluntary and financially incentivized. Such a mixed model can be sustained given current demographic trends, though external support would be needed to train and equip it.

Tier 3: Defense of Population Centers and Critical Infrastructure, Plus Naval and Air Forces

The last big piece of Ukraine’s future defense needs pertains to its cities and critical infrastructure. Although he failed to crack Ukraine’s will, Putin has found a way to make life miserable for most Ukrainian city dwellers without consistently having his forces target their apartment buildings, schools, or hospitals (though he has done all those things, too): rather, Russian forces have targeted Ukraine’s electricity and power grids—during winters, in particular.

No air and missile defense system can ensure an end to such barbaric behavior if Russia undertakes it again. But Ukraine needs a reasonable strategy to protect its major cities, particularly against missile attack with large warheads of the type that do the greatest damage to major infrastructure. The current architecture of defensive weapons being used now—Patriot batteries and other U.S. systems, plus European equivalents—is not a bad template. However, a systematic assessment of the necessary magazine depth of interceptors is still needed. How many interceptors Ukraine should build, buy, and store remains an open question. Russia has been averaging some twenty to twenty-five missile strikes a day against Ukraine over the course of the war, and Ukraine has averaged shooting down 80 percent—though effectiveness varies considerably with the type of incoming missile.31 One way to calculate the answer is to adopt the standard that Ukraine should have a fair chance at shooting down virtually any incoming missile, and that it needs a full winter’s supply of missiles in inventory to ensure Russia cannot bring it to its knees while it awaits contracts and deliveries from outside powers. Those two parameters imply a need for twenty-five missiles per day for two hundred days, or five thousand defensive interceptor missiles of various types. Future Russian attacks could be more or less intensive, of course, so this planning benchmark should be viewed as a rough estimate and not a definitive prediction. Complementing the stockpiling, therefore, should be planning for how to acquire additional interceptors from foreign suppliers promptly in the event conflict resumes.

Although an air force might not be crucial for Ukraine, as noted above, it could make sense to sustain the new fledgling force of F-16s that Ukraine has been acquiring of late—if only to complicate Russian temptations to use its own air force against Ukraine as part of an integrated attack on cities. Ukrainian naval forces, which have been impressive in this war largely through their use of missiles and unmanned systems against Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, should continue to sustain their capabilities as well.

Robust Cease-fire Provisions and Broader Security Architecture

A stable and secure future Ukraine will not depend exclusively on the nature of its future armed forces. Ukraine should plan to build a military with a robust defensive capability, irrespective of whether good cease-fire arrangements are instituted and respected—and irrespective of whether Ukraine winds up in NATO or a different security architecture of various bilateral security relationships (as currently planned). But complementary mechanisms could be useful for improving Ukraine’s sense of confidence and security further.

Ideally, a cease-fire agreement between Ukraine and Russia should aim not just to bring the fighting to a halt, but also prevent it from restarting in a way that could provide a decisive advantage to Russia.32 In the abstract, this step could be accomplished by adding provisions that would inhibit deliberate violations and otherwise raise the cost of recidivism to prohibitive levels. This can take various forms that are not mutually exclusive. One is to multilateralize the cease-fire agreement by, for example, involving the United Nations in the final agreement, if only through official endorsement by the Security Council and General Assembly. On the face of it, this would seem to add little to Ukraine’s security, but it would force Russia to consider the political and reputational costs associated with blatantly defying the United Nations—something that it would not do lightly given the effort it has made to woo the Global South in support of its cause. Violating a UN resolution can also facilitate the later imposition of multilateral sanctions, something else Russia would have to consider.

Similar logic also applies to the involvement of an international cease-fire monitoring force to ensure compliance. Russia has not typically favored the deployment of international monitors in contested areas—certainly not areas they consider to be sovereign territory—but that would not preclude the two sides from allowing them on Ukrainian territory. Were such a force to comprise Chinese and Indian personnel, for example—not out of the question if Moscow is ultimately supportive of a negotiated armistice—Russia would have to consider the consequences of embarrassing both major powers were it to flagrantly violate an agreement they were clearly committed to supporting. Again, it would make Putin think twice given how important both China and India are to Russia’s economy and international standing.

Regardless of whether Russia agrees to cease-fire monitors, other terms and conditions of a cease-fire can contribute to the future defense of Ukraine by providing early and unambiguous warning of hostile intent. Such warning can be critical for the timely mobilization, deployment, and readiness of defensive forces to deter and ultimately defeat an emerging threat. The provisions of a cease-fire agreement can create such a tripwire through, for example, prohibiting the concentration of forces—including in the guise of exercises—above a certain amount and type within a designated distance of the LOC, and allowing regular overflight, challenge inspections, and placement of autonomous surveillance sensors in areas of concern. There are several precedents for those kinds of arrangement that, moreover, should take effect for Ukraine’s entire defense perimeter, not just the frozen battle lines.

Western military personnel could also be stationed in Ukraine as part of any agreement, whether as part of a UN monitoring force or separate training mission. Personnel need not be organized or deployed as combat formations, but they could be in uniform and their sponsoring countries could pledge in advance to defend them (rather than withdraw them, as happened following the collapse of the Minsk agreement), should conflict appear imminent. Admittedly, this would be a difficult proposition for Russia to swallow—but if framed as an alternative to NATO membership for Ukraine, it could be more feasible. In other words, the Kremlin could be more willing to have NATO in Ukraine than to have Ukraine in NATO. That assessment would be true even if there were no formal armistice but simply a gradual petering out of the fighting.

Such an arrangement to secure Ukraine’s future will doubtless have its detractors. Some critics will argue that a multilayered defense system is no substitute for NATO Article 5 security guarantees. Others could also question either the desirability or viability of continued Western support. Ukraine’s security could well be enhanced by becoming a member of NATO, but this is not a realistic prospect at this time nor one likely to promote a timely end to the fighting, let alone a larger settlement of the war. At the same time, it is clearly not in the West’s interest to see Ukraine succumb to Russia’s aggression and be either absorbed by it or turned into a weak vassal state, much as Belarus has now become. Such an outcome would not only undermine the security of the West but also weaken the prevailing rules-based international order and perhaps put NATO territory at risk. The cost of providing Ukraine with the wherewithal to defend itself will be substantial, but it constitutes a fraction of what would be necessary if it is defeated and the West is forced to respond with much higher levels of defense spending.

The good news is that the infrastructure for such long-term support is already in place in the form of bilateral security agreements with over twenty countries.33 The U.S.-Ukraine agreement, for example, represents a ten-year renewable commitment.34 Although the provision of military equipment and munitions has been slow because of the erosion of the United States’ and Europe’s defense industrial bases since the end of the Cold War, this problem is being steadily rectified. New investments and sources of production are now beginning to bear fruit.

Conclusion

In summary, planning for the long-term defense of Ukraine in the absence of NATO security guarantees needs to begin now, regardless of the timing of cease-fire negotiations. Ukraine will play the lead role, to be sure, but its many Western friends can help, possibly under NATO auspices (even absent inviting Ukraine to join the alliance). Western countries have a major stake in Ukraine’s future success and will have to play a significant role in resourcing the effort, so their involvement at the planning stage is crucial, too. Undertaking this task together will enhance Ukraine’s negotiating position at any cease-fire discussions, among other benefits.

If and when cease-fire negotiations begin, the goal should be not just to end the fighting but, to the extent possible, enhance Ukraine’s defensive prospects thereafter. This can be achieved in a variety of ways, such as through monitoring arrangements, buffer zones, and restrictions on the deployment of forces in the vicinity of the LOC. While such provisions could prolong negotiations, pursuing them is legitimate and worthwhile. The terms of a cease-fire should not compromise Ukraine’s ability to defend itself against future aggression, including by restricting its defense capabilities or the provision of Western military assistance and training.

Once a cease-fire is reached, no time should be wasted to begin the process of bolstering Ukraine’s defenses against possible future Russian aggression. In the short term, the level of military and financial support should not decline to take advantage of what could simply be a pause in the fighting and help Ukraine create its robust and sustainable self-defense force.

Standing up and sustaining a multilayered defense system in the aftermath of a cease-fire agreement is a demanding long-term challenge for Ukraine, but not an impossible one. Fortunately, Ukraine will begin the process with an impressive military that has achieved many, if not all, of its core goals—including the most important, existential ones—over the past three years. Evolving from the current situation to a sustainable and robust defense is therefore a manageable task. This strategy does, however, rely on continued Western military and economic assistance to ensure the defense system’s credibility as an effective deterrent to potential Russian recidivism. A substantial level of support will be necessary, therefore, for many years, even decades, if some current armistice agreements are any guide.

Comparison with the military forces of Israel and South Korea suggests that Ukraine will need a steady state defense budget of $20 billion to $40 billion a year.35 With Ukraine’s gross domestic product (GDP) around $600 billion a year, but likely to recover quickly once hostilities end, that kind of military burden would wind up between 3 to 6 percent of GDP—potentially quite a bit more than the 4 percent it devoted to defense prior to 2022, but much less than today’s double-digit figures and well within the bounds of what a country living in a dangerous neighborhood could expect to pay.36 A chunk of that burden would likely be borne by outsiders, including initial weapons purchases required to fill up magazine stocks and deploy better air and missile defenses around the country (and outfit the strategic reserve maneuver force). As outside nations have contributed well over $100 billion over the past three years in military assistance to Ukraine, peace would be a bargain compared to war—not only in financial terms, of course, but in terms of human lives and escalatory risks.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation for those who provided invaluable comments on previous drafts of this report, including Steven Biddle, Nathan Colvin, Liana Fix, Thomas Graham, and members of the Council Study Group on Securing Ukraine’s Future.

About the Authors

Michael E. O’Hanlon is a senior fellow and director of research in the foreign policy program at the Brookings Institution, where he specializes in U.S. defense strategy and budgets, the use of military force, and American national security policy. He directs the Strobe Talbott Center on Security, Strategy and Technology, and is the inaugural holder of the Philip H. Knight chair in defense and strategy. His forthcoming book is To Dare Mighty Things: U.S. Defense Strategy Since the Revolution.

Paul B. Stares is the General John W. Vessey senior fellow for conflict prevention and director of the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). An expert on conflict prevention and a regular commentator on current affairs, he is the author or editor of nine books on U.S. security policy and international relations. His latest book, Preventive Engagement: How America Can Avoid War, Stay Strong, and Keep the Peace, provides a comprehensive blueprint for how the United States can manage a more turbulent and dangerous world. t