- China

- RealEcon

- Topics

-

Regions

Featured

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

Featured

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

Predictions of the Candidates’ Promises to “Secure America”

This blog post was coauthored with my research associate, Jennifer Wilson.

Last week, President Obama announced the unprecedented step of connecting U.S. national security with the threats posed by climate change. Obama’s Presidential Memorandum directs twenty federal agencies to integrate climate change into national security policy and planning—meaning collecting climate science data and identifying how climate change will affect agency missions. Melting ice and rising temperatures are not traditionally considered national security concerns, but the memorandum is the most recent development in a years-long effort to focus on the dangers of global environmental change that has been applauded by security professionals and environmentalists alike.

Tonight, in the first presidential debate of the general election, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump will argue, among other topics, the best way to “secure America.” With viewership expected to “shatter records,” the debate offers an unprecedented opportunity for the candidates to reframe national security discussions and re-examine what it means for America to be “secure.” For example, the would-be leaders could allay fears of terrorism and remind the public, as President Obama has, that the self-proclaimed Islamic State poses no existential threat to the United States. In fact, they could tell viewers that their chances of being killed by an Islamist terrorist attack are lower than being killed by falling televisions or furniture. Having freed up air time, the candidates could then go on to debate substantive policies that could actually make Americans more secure, like a plan to stem gun violence, or to protect private critical infrastructure from cyber attacks.

However, if the primary debates are any indicator, these topics are likely to get little if any attention.

Should anyone need a reminder, there were twenty-eight Republican and Democratic primary debates held between August 2015 and April 2016. Foreign affairs were hardly discussed, but when the topic was brought up it was almost exclusively in terms of threats emanating from abroad—like when Wolf Blitzer cited a claim that the United States now faces the greatest terror threat since 9/11, or when Gwen Ifill asked Clinton if “we were ready” for the next attack sure to come around the corner. The Islamic State was mentioned over five hundred times in total, and in all but four of the debates. Particularly in Republican forums, the candidates seemed to be in a contest to endorse either categorical war crimes, or a continuation of existing policies but with added “resolve” or “leadership.” All candidates proposed unnamed “countries in the region” to demonstrate heretofore nonexistent political will to defeat the Islamic State.

In contrast, climate change was brought up less than a fifth as many times as the Islamic State. Evidence of climate change is unequivocal, and there is a near-consensus among knowledgeable climate scientists that the world is getting warmer, and will continue to do so. Yet, at the presidential forums, much of the discussion centered around whether climate change was real or not, or, in the Republican debates, whether it deserved any government attention. (Governor John Kasich, for example, said that instead of finalizing an historic universal climate agreement in Paris, the assembled heads of state “should have been talking about destroying ISIS”).

It would require tremendous optimism to hope that the reconception of national security that Obama’s memorandum might have fostered would continue during this debate. Gauging by the tenor of this election season, viewers should instead expect Clinton and Trump to exaggerate the threats facing the United States, and to offer their plans as the only solutions to confront them. We will hear promises to shield Americans from radical Islamists, plans to “beef up” the military, and at least one misrepresentation of the president’s most sacred responsibility (reminder: it’s to protect and defend the Constitution, not to keep Americans safe).

Viewers will be disappointed should they hope to hear how the candidates would ease U.S. reliance on fossil fuels, or whether they will seek updated congressional authority for overseas counterterrorism campaigns, or how they will shift federal resources away from defense and intelligence budgets to address infrastructure and economic development shortfalls within the United States. Even when discussing one policy about which the candidates agree, the establishment of a “big, beautiful” safe zone in Syria, Clinton and Trump both are long on promises of efficacy and short on operational details.

Endless dissection of performance and over-analysis of poll numbers will follow the debate. However, the “winner” will assuredly be the Islamic State, whose capabilities and threat will be inflated by both candidates. The group will receive millions of dollars’ worth of free advertising and a confirmation of its undeserved international status. The “losers” will be those American citizens interested in a substantive discussion of policies, details about how they would be implemented, or a responsible assessment of the role of the United States in the world.

The Colombia Peace Agreement Does not Mean the End of U.S. Involvement

Aaron Picozzi is the research associate for the military fellows at the Council on Foreign Relations, is a Coast Guard veteran, and currently serves in the Army National Guard.

A recent victory in the half century conflict in Colombia was marked by an agreement between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (known by its Spanish acronym, FARC) leader Rodrigo Londono, and President Juan Manual Santos. But as thousands of FARC rebels hand their weapons over to a UN mission, many will be faced with a difficult consequence of the peace—a lifestyle change from fighting for an ideology, to attempting to rejoin society as a former solider. With the folding of the FARC organization comes the question: what will happen to the Colombian cocaine trade that was so closely tied to the rebel group?

It is doubtful the dissolution of the FARC will bring an end to Colombia’s participation in global cocaine trade—a business which nets the FARC anywhere from $200 million to $3.5 billion annually, and is responsible for 90 percent of total cocaine used in the United States. Faced with questionable futures and the disappearance of a clear command structure, rebels may continue the lucrative criminal activities they have perfected over years of conflict, but this time they will be separate from the organizational structure the FARC once provided.

Colombia has not carried out their war on drugs alone. The United States has played an integral role in the fight, funneling over six billion dollars, $4.8 billion of which went directly to the Colombian military or police, over eight years through the counternarcotics program Plan Colombia. The direct efforts of the United States within Colombian borders, which include military raids and the eradication of coca crops by spraying chemicals, have drawn criticism from neighboring countries and Colombian citizens alike, yet there is a U.S. military option that circumvents many of the chief complaints surrounding U.S.–Latin American foreign policy.

To support the FARC stand-down, while congruently fighting the drug trade, the United States can double down on a technique it already employs. In 2015, the Coast Guard stopped 144.8 metric tons of illegal cocaine from reaching its destination through maritime and air interdiction campaigns. These techniques have been employed through cooperative efforts, such as the Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) directed Joint Interagency Task Force South (JIATF-S), a multi-organization group comprising members from all five branches of U.S. military service, multiple agencies within the Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Intelligence Community, as well as representatives from various countries, both near and far from the SOUTHCOM area of responsibility. This group is focused on the eradication of illegal drug trafficking. Continued and increased use of JIATF-S and the U.S. Coast Guard counter-drug teams can help combat the transnational drug trade. Unfortunately, the U.S. Coast Guard is projecting lower interdiction numbers for 2017 due to the U.S Navy’s plan for reducing the number of sea and air assets allocated to JIATF-S mission set. A reduction in dedicated assets will create a more difficult counter-drug operation, yielding fewer interdictions, and opening the door to those who wish to capitalize on the destabilized Colombian drug syndicate.

The use of air and sea assets allows the U.S. military to assist Colombia directly, without carrying the stigma of a foreign military incursion. This focus on fighting the Colombian drug trade would also help with the herculean task of reintegrating the estimated 6,000 to 7,000 fighters and 8,500 supplementary civilian supporters from FARC; if the efficacy of the transnational drug trade is reduced, it may dissuade former drug-dealing transitioning FARC members from continuing their involvement. While rebel reintegration programs currently exist in Colombia, they are costly, lengthy, and garner a recidivism rate of roughly twenty five percent. Many rebels know only the militant work required to operate in a jungle combat environment or the illicit activity that financed their operation.

During the FARC detente, the United States can increase offshore interdiction activity without evoking feelings of Reaganesque Latin American policy. By reinvesting in maritime and air operations targeting the Colombian drug trade, the United States can continue its efforts without political meddling. These actions can both support the peace plans, while simultaneously protecting the United States from the threats of transnational drug organizations.

How Not to Red Team

During the 2015 summer travel season, airline passengers were stunned by a finding that was never supposed to be made public, but which leaked to ABC News. Auditors from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) had successfully smuggled weapons and fake explosives past Transportation Security Administration (TSA) checkpoints sixty-seven times out of seventy attempts at multiple domestic airports earlier that year. The DHS Inspector General John Roth later told a Congress that the auditors did not have “any specialized background or training,” meaning they were not especially proficient or skilled red teamers.

Roth also warned in prepared congressional testimony that after 115 audits conducted over the previous eleven years and “despite spending billions on aviation security technology, our testing of certain systems has revealed no resulting improvement.” Roth added: “Our audits have repeatedly found that human error—often a simple failure to follow protocol—poses significant vulnerabilities.” This revelation of inadequate security at domestic airports led to a series of reforms and retraining within TSA, which explained the longer lines that passengers faced in early 2016.

The results of these leaked covert tests relate to a new Government Accountability Office (GAO) report that reviewed the results of TSA’s own testing of its Transportation Security Officers (TSO). There were two remarkable GAO findings about these covert tests, which the TSA calls its Aviation Screening Assessment Program (ASAP). Both findings violate two of my red team best practices: vulnerability probes should be independent and unannounced, and conducted in a manner that resembles how motivated adversaries would attempt to breach a system; and institutions must be willing to hear the bad news from the red team, and develop a work plan to mitigate the vulnerabilities that only the red teamers can uncover.

First, TSA had determined that the TSOs performed much better at finding prohibited items when covert tests were conducted by TSA field officers at local airports, when compared to those by outside contractors up to October 2015. The GAO report states:

“According to TSA officials, TSOs at these forty airports performed more poorly in the ASAP tests conducted by the contractor personnel as compared to the prior ASAP testing done by the local TSA personnel—indicating that these prior-year pass rates were likely showing a higher level of performance than was actually the case….

“According to TSA officials, initial results from the contractor’s work seem to confirm their prior concerns (before the contractor testing was conducted) that problems exist with successfully maintaining the covert nature of tests at airports…With respect to the difficulty in maintaining the covert nature of the tests, TSA officials at seven of ten of the airports we contacted indicated challenges with obtaining anonymous role players to ensure that the ASAP tests remain covert. For example, TSA officials at one airport we visited reported having to rely on the availability of state and local government employees and U.S. Customs and Border Protection personnel to perform as role players. Another smaller airport we visited reported challenges finding role players among local TSA personnel that the TSOs working the screening lanes would not recognize. As a result, they tend to use new hires, National Guard, Federal Aviation Administration, and Federal Bureau of Investigation personnel.”

In other words, the TSOs could identify the testers by their appearance or knew them personally. The testers’ appearances or behaviors while standing in the screening lines could have also given away their occupation as government employees and not civilian travelers. This can happen even unconsciously when covert testers have a professional affinity with defenders, and want them to succeed at stopping their smuggling of prohibited items. Finally, the testers may have known airport workers or TSOs individually, and tipped-them off ahead of time. This happens far too frequently in private sector and government security testing. (TSA officials responded to the GAO finding by stating they would give local security directors more authority to use testers that were not government employees.)

The second finding from the GAO report was even more disturbing. The entire point of testing the security of a defensive system is to identify vulnerabilities in order to provide the defenders with prioritized, corrective measures that improve security. Unfortunately, the GAO investigators found that:

“TSA headquarters does not require FSDs [Federal Security Directors] to implement recommendations from the six-month cycle reports nor does it track whether the recommendations have been implemented, or conversely, reasons for not implementing them. TSA officials stated that the various recommendations cited in the cycle reports are strictly for the consideration of FSDs in the field and implementation is not mandatory.”

TSA’s senior leaders did not monitor whether local security officials were implementing the corrective measures, which were revealed to be necessary by the covert tests. If there are no mandatory requirements to reduce vulnerabilities uncovered by covert tests, then such testing is pointless. A red team vulnerability probe that is conducted and ignored can be far worse than one that is never conducted at all. These two red team “worst practices” are not unique to TSA. However, given terrorists’ longstanding interests of attacking commercial aircraft, as well as the sobering DHS findings from 2015, this new GAO report should be a cause of concern for policymakers and airline passengers alike.

Hackers, Pen Tests, and Security Research: A Conversation with Chris Rohlf

I spoke with Chris Rohlf, former head of Yahoo’s red team in New York and a thoughtful and respected voice in the security community. Chris has extensive experience as a pen tester, developer, engineer, and consultant for various organizations, including within the Department of Defense and on the Black Hat review board. We discuss how the government should bridge the gap with the security community, like the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx) and the recent Hack the Pentagon bug bounty. We also talk about how organizations will grapple with the challenges presented by the Internet of Things, the “IoT”: the growing network of objects that sense and interact with each other. Chris offers useful advice for aspiring hackers, and three practical suggestions for how you can protect your own devices. Follow Chris on Twitter @chrisrohlf.

CFR Model Diplomacy: Students as Policymakers

When asked to recommend readings for international relations and foreign policy syllabi, I regularly send people to my summaries of important policy-relevant findings from academic journals. But for this fall, I wanted to recommend an immersive teaching tool that goes beyond reading lists and puts students in the policymaker hot seat, where they work in teams to make judgments and decisions based upon limited information and timelines.

Our new Model Diplomacy initiative features case-based simulations that offer free course guides, multimedia content, research materials, and exercises for high school teachers and undergraduate professors to use in the classroom. It includes thirteen timely and relevant cases, from a humanitarian intervention in South Sudan to an escalating cyber clash with China. As of this summer, 547 institutions are participating in Model Diplomacy, representing some 68 countries.

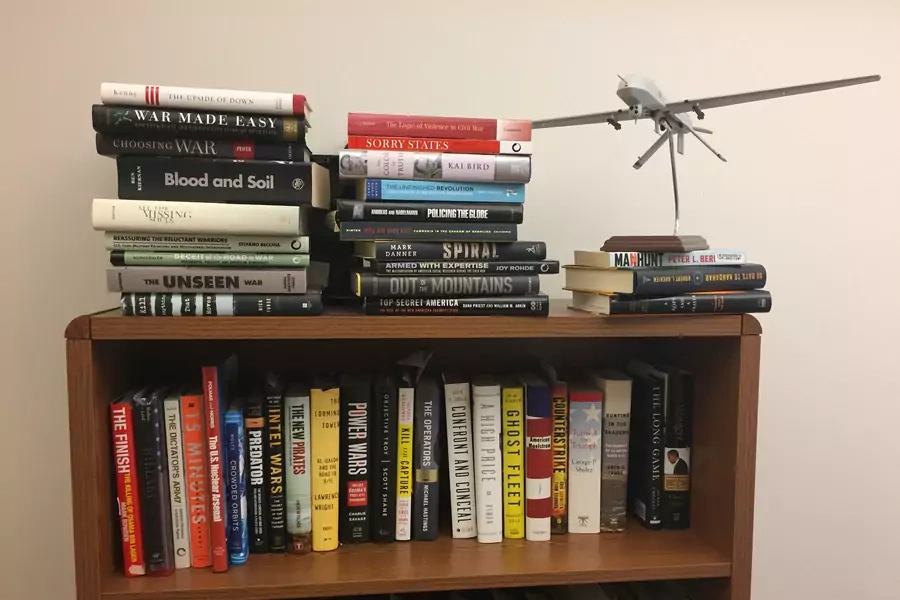

One case that I have developed and updated is a National Security Council (NSC) meeting simulation that debates the merits of authorizing a drone strike in Pakistan against Ayman al-Zawahiri. Students are told:

Last week, the CIA suddenly came upon highly credible evidence of Zawahiri’s location—inside a large compound in a densely populated city in the Federally Adminstrated Tribal Areas. The compound also houses an estimated three dozen women and children. A trusted source from within Pakistan, who has provided credible information in the past, told his CIA liaison that Zawahiri will be meeting several high-level al-Qaeda operatives at his compound at 2:00 a.m. tomorrow. Among those believed to be attending is an American who is also a senior al-Qaeda operative. The president must decide quickly whether to authorize action to kill or capture Zawahiri.

For a fairly dramatic video of some remarkable teenagers debating a drone strike or capture operation against Zawahiri, see the Model Diplomacy homepage. To learn more, and to see what other tools CFR offers for teachers, professors, and students, visit CFR Campus. Welcome back to school.

Online Store

Online Store