- China

- RealEcon

- Topics

-

Regions

Featured

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

Featured

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

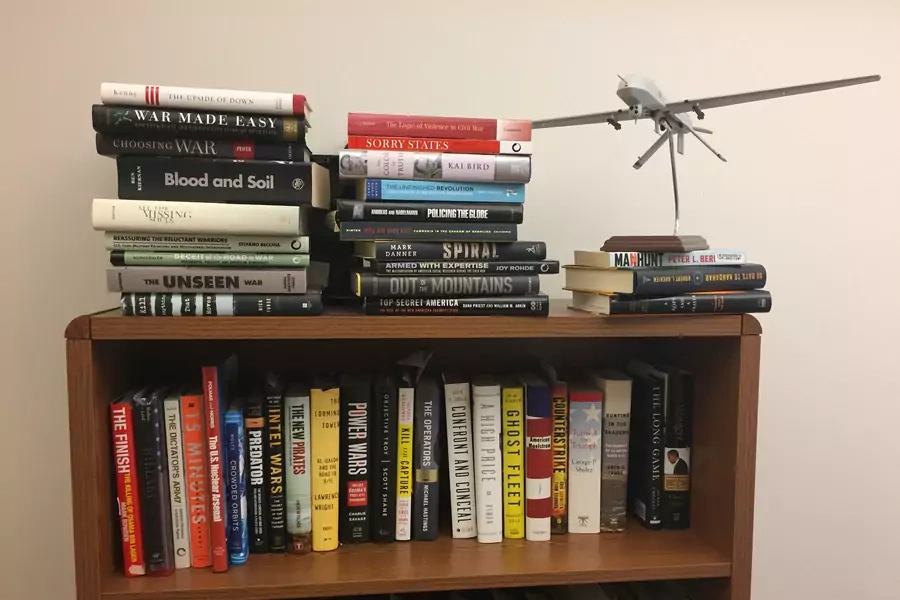

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

The Pentagon Plans for Autonomous Systems

Today, the Defense Science Board (DSB) released a long-awaited study, simply titled Autonomy. Since the late 1950s, the DSB has consistently been at the forefront of investigating and providing policy guidance for cutting-edge scientific, technological, and manufacturing issues. Many of these reports are available in full online and are worth reading.

The Autonomy study task force, led by Dr. Ruth David and Maj. Gen. Paul Nielsen (ret.), was directed in 2014 “to identify the science, engineering, and policy problems that must be addressed to facilitate greater operational use of autonomy across all warfighting domains.” The study begins with a practical overview of what autonomous means, and how it has enhanced operations in the private sector and throughout the military. According to the authors: “To be autonomous, a system must have the capability to independently compose and select among different courses of action to accomplish goals based on its knowledge and understanding of the world, itself, and the situation.” They also present four categories for characterizing the technology and engineering required for autonomous systems: Sense (sensors), Think/Decide (artificial intelligence computation power), Act (actuators and mobility), and Team (human-machine collaboration).

The latter category of human interactions with autonomous systems is a reoccurring theme throughout the study. The authors emphasize that it will be more important to continuously educate and train human users than to develop the software and hardware for autonomous systems. The proliferation of such systems is already prevalent in the private sector, where there are few intelligent adversaries looking to corrupt or defeat them. The more complex challenge will be in assuring that policymakers and military operators can trust that more autonomous weapons platforms and networks “perform effectively in their intended use and that such use will not result in high-regret, unintended consequences,” as the authors indicate. They propose extensive use of early red teaming and modeling and simulations to identify and overcome inevitable vulnerabilities.

While technologists and futurists often propose far greater adaptation of autonomous systems in U.S. defense planning, the study warns of several adversarial uses of autonomy (many of which red teamers warned of regarding network-centric-warfare fifteen years ago):

“The potential exploitations the U.S. could face include low observability throughout the entire spectrum from sound to visual light, the ability to swarm with large numbers of low-cost vehicles to overwhelm sensors and exhaust the supply of effectors, and maintaining both endurance and persistence through autonomous or remotely piloted vehicles….

The U.S. will face a wide spectrum of threats with varying kinds of autonomous capabilities across every physical domain—land, sea, undersea, air, and space—and in the virtual domain of cyberspace as well.”

The study also identifies ten projects that could be started immediately to investigate near-term benefits of autonomy. The most notable of these is “Project #6: Automated cyber-response,” which is in response to the move from attempting (and failing) to secure computer networks based upon past adversarial attacks, to developing defensible networks that can sense, characterize, and thwart attacks in real time. U.S. Cyber Command is tasked with leading this project for $50 million over the next two to three years, which includes the ambitious goal of “Develop a global clandestine infrastructure that will enable the deployment of the defensive option to thwart an attack.”

The study addresses, but does not make specific recommendations for the well-publicized and controversial issue of fully autonomous lethal systems used for offensive operations. However, it does call for “autonomous ISR analysis, interpretation, option generation, and resource allocation” to reduce the human requirements and time needed (currently twenty-four hours) to process and distribute the air tasking order for combat units to strike. Like an increasing number of other military missions, this is another example where machines can make warfare easier, faster, and safer for U.S. servicemembers. Whether, and how often, those wars occur remain up to elected civilian leaders. Read the Defense Science Board Autonomy study for a smart—and policy-relevant—overview on where the Pentagon is planning to head regarding autonomous systems.

Civil-Military Relations: A Conversation with Kori Schake

Today I spoke with Kori Schake, Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. We spoke about her new book co-edited with Jim Mattis, Warriors and Citizens: American Views of our Military (Hoover 2016) and what their research reveals about how the public and elites currently view the military—and what that means for national security policy. Kori also offered some candid advice for young national security scholars and an uplifting story featuring the great Harvard Professor Ernie May from early in her career. Follow her work on Twitter @KoriSchake, and listen to my conversation with one of the smartest and most well-respected experts in national security and military affairs:

Reviewing the Pentagon’s ISIS Body Counts

Four months after President Obama pledged to the nation in September 2014 “we will degrade and ultimately destroy ISIL,” reporters challenged Pentagon spokesperson Rear Adm. John Kirby about his assertion that “We know that we’ve killed hundreds of their forces.” One reporter asked directly, “can you be more specific on that number?” Kirby replied tersely:

“I cannot give you a more specific number of how many ISIL fighters…[W]e don’t have the ability to count every nose that we shwack [sic]….And we’re not getting into an issue of body counts. And that’s why I don’t have that number handy. I wouldn’t have asked my staff to give me that number before I came out here. It’s simply not a relevant figure.”

Sixteen days later, a U.S. government official offered just such a number: 6,000. Body counts have a long and infamous history in modern U.S. wars, from Vietnam, to Afghanistan, to Iraq, and now in the campaign against the self-proclaimed Islamic State. In each of these conflicts, the U.S. government released estimates of enemy fighters killed, all while either doubting the voracity of those numbers or admitting they were largely irrelevant to achieving the longer-term strategic objective. As Gen. Westmoreland said after the Vietnam War: “Statistics were, admittedly, an imperfect gauge of progress, yet in the absence of conventional front lines, how else to measure it?”

I have a piece in Foreign Policy today that reviews and questions the Pentagon’s estimates of Islamic State fighters killed and lists the data points it has released:

March 3, 2015: 8,500

June 1, 2015: 13,000

July 29, 2015: 15,000

October 12, 2015: 20,000

November 30, 2015: 23,000

January 6, 2016: 25,500

April 12, 2016: 25,000/26,000

August 10, 2016: 45,000

For more on why this recent 80 percent increase is improbable, as well as an official response from the U.S. Central Command, read the full article.

Why Donald Trump is Wrong About NATO

Dan Alles is an intern in the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.

At the 2016 Warsaw Summit last month, leaders from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) announced that they will deploy four multinational battalions to Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. This decision sends an important and reassuring message to the world at a time when some, like Donald Trump, are questioning the reliability and sustainability of the alliance altogether. Although Trump’s comments about burden-sharing have some merit, his judgements are misguided; weakening the current deterrence posture or abandoning the alliance would be disastrous for U.S. and global security. NATO is not only a collective deterrent against Russian aggression, but also a political and military organization that has adapted to meet twenty-first century challenges. Through these developments, NATO has become an indispensable part of U.S. security, and despite some limitations, it should not be abandoned.

Although it was founded on the basis of collective defense, NATO broadened the scope of its missions over the past twenty-five years. Today, NATO is a leader in global crisis management and undertakes a wide variety of direct military operations to support this mission. These operations span the globe, from the alliance’s train and equip programs in Afghanistan, to its post-9/11 maritime surveillance programs in the Mediterranean Sea. This fall, NATO will also finalize plans to restart training and capacity building inside Iraq. NATO’s previous operation there, the NATO Training Mission-Iraq, concluded in 2011, but the rise of the self-proclaimed Islamic State has pushed the alliance to return.

NATO is able to take action to prevent conflicts in support of a United Nations mandate or at the invitation of a sovereign government. In accordance, NATO also maintains a peace-support presence of about 4,500 troops in Kosovo and continues to support the African Union in its peacekeeping and counter-piracy operations.

NATO’s evolution since the fall of the Soviet Union resulted in an immensely integrated military alliance system with a global presence. As such, the benefits of NATO now transcend its direct military footprint and incorporate a variety of tactical advantages as well. These advantages include:

A ready-made multilateral coalition prepared to respond to crisis. A world without NATO would be one where, if the United States wanted to avoid acting unilaterally, it would have to construct a novel coalition for every conflict that arises. Not only would this take more time and cost more money, but it would also be less effective, as the alliance has already worked out its policies and procedures and shared its best practices.

Joint training and deterrence exercises. Conducting training exercises allows NATO to maintain a force readiness and deter potential antagonists. Moreover, joint exercises offer zero-consequence trial runs to test and validate new concepts in demanding crisis situations. This in turn improves the interoperability of both military and civilian organizations.

Consultation and sharing of assessments, military plans and intelligence. NATO is an effective vehicle for intelligence and information sharing among member states. Its mechanisms for intelligence sharing improves coherence among partners, including other international organizations like the United Nations and European Union.

Sharing of military resources and infrastructure. During the Gulf War, NATO did not take a direct role in combat operations, but cooperated to provide logistical support to member forces in region, including organizing transportation, landing rights, port use, air traffic control, and medical support. Similarly, though NATO is not involved in the current coalition against the self-proclaimed Islamic State, member states contribute resources and facilities to the fight. Turkey’s Incirlik air base, where coalition troops fly sortie missions over Syria and Iraq, is just one example. According to U.S. Air Force data, there was a thirty percent increase in bombs dropped after missions from Incirlik began in 2015.

The overwhelming evidence for NATO’s strategic importance to the United States demonstrates that Trump’s comments about NATO were misguided. Moreover, approaching the alliance with threats to withdraw does not increase U.S. leverage in negotiations. Instead, it merely downplays U.S. leadership and emboldens Russia. In light of Russian action in Georgia and Crimea, and the extension of the Eurasian Economic Union—a trading bloc comprising Russia and former Soviet satellites—the United States should maintain its leadership role in NATO and encourage members to meet spending goals. Today, experts believe a Russian invasion of the Baltic Republics would be successful in a mere sixty hours, leaving NATO with limited bloody options to respond. The agreements at the Warsaw Summit were steps to increasing NATO’s defense posture, but more could be done to ensure that its tactical strengths are matched with an equally strong foundation for deterrence.

Revisiting President Reagan’s Iran Arms-for-Hostages Initiative

The Wall Street Journal published an important story about the Obama administration’s decision in January to ship $400 million, which was first converted into Swiss and Dutch currencies, to Iran on board a cargo plane. The plane delivering the money had reportedly arrived at Tehran’s Mehrabad airport on the same date that four U.S. citizens were released by the government of Iran.

This money was owed to Iran for over thirty-five years, dating back to U.S. weapon sales that the Shah’s government paid for, but had not yet been delivered before the revolution. Under President Jimmy Carter, Iran was the number one recipient of all global arms exports. For example, between 1976 and 1978, over $8 billion (in current dollars) worth of weapons were delivered to Iran each year. Thus, the $400 million provided in January 2016 was the first shipment of $1.7 billion (this includes interest) that Obama announced concurrently with the nuclear deal: “Iran will be returned its own funds, including appropriate interest, but much less than the amount Iran sought.”

Immediately, charges of paying a ransom for the release of the U.S. citizens was leveled at the White House from opponents of the nuclear deal. Sen. Tom Cotton accused Obama of paying “a $1.7 billion ransom to the ayatollahs for U.S. hostages,” while Sen. Mark Kirk announced: “Paying ransom to kidnappers puts Americans even more at risk.”

Presidential attempts to secure the release of U.S. citizens believed to be under Iranian control have a notorious history. President Ronald Reagan’s Iran arms-for-hostage scandal is poorly understood by many, and even among current U.S. government staffers and officials that I speak with. The shorthand historical memory is that, “Reagan gave weapons to Iran for hostages.” Actually, the initiative was partially an effort to counter purported growing Soviet influence within Iran, which a 1985 Special National Intelligence Estimate had warned of. One potential source of leverage that could be reestablished was weakening the total arms embargo that had been in place since 1980. Another side aspect of the arrangement was to raise money—in direct violation of the Bolan amendments—that would support the Contra rebels fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

Still, as the masterful Office of Independent Counsel for Iran/Contra Matters report led by Lawrence Walsh makes clear, President Reagan hoped to secure the release of U.S. hostages being held in Lebanon in exchange for U.S. weapons. The scandal stained the president’s reputation, after he first went before the American people and proclaimed “We did not—repeat—did not trade weapons or anything else for hostages, nor will we,” but four months later admitted “what began as a strategic opening to Iran deteriorated, in its implementation, into trading arms for hostages. This runs counter to my own beliefs.”

The final outcome of the arms-for-hostages disaster was two U.S. citizens released (Reverend Benjamin Weir and Father Lawrence Jenco) and two new hostages taken (Frank Reed and Joseph Cicippio). In exchange for no net gain in released U.S. citizens, President Reagan authorized the delivery to Iran—from U.S.-supplied Israeli stockpiles—the following advanced weapons:

Aug. 20, 1985: 96 TOW missiles

Sep. 14, 1985: 408 TOW missiles

Nov. 24, 1985: 18 HAWK missiles

Feb. 18, 1986: 500 TOW missiles

Feb. 27, 1986: 500 TOW missiles

May 25, 1986: HAWK spare parts

Aug. 3, 1986: HAWK spare parts

Oct. 28, 1986: 500 TOW missiles

Online Store

Online Store