- China

- RealEcon

- Topics

-

Regions

Featured

-

Explainers

Featured

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

Featured

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

Featured

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Related Sites

- More

Blogs

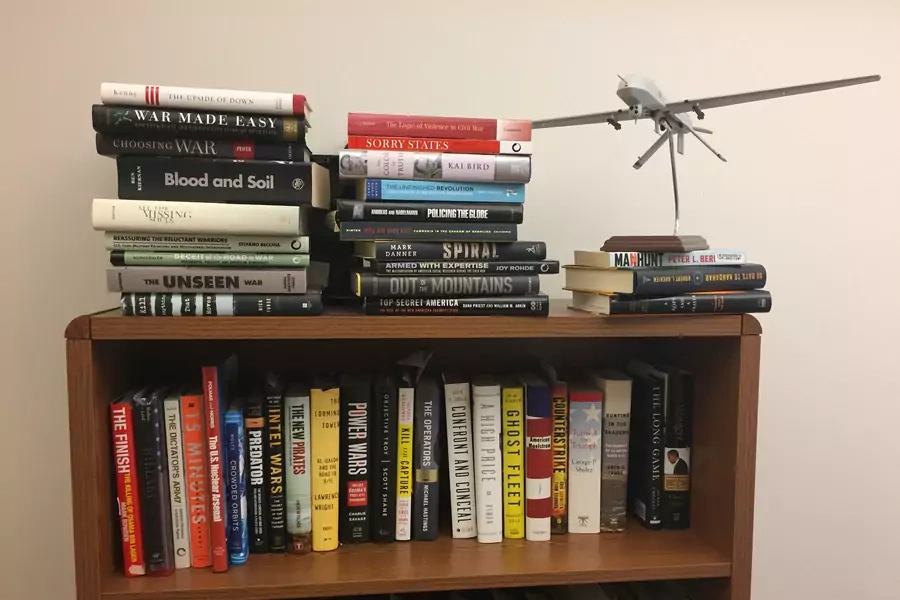

Politics, Power, and Preventive Action

Latest Post

Signing Off

Today is my last day at the Council on Foreign Relations after eight and one-half fun and fulfilling years. An archive of everything I authored or co-authored remains here. Subsequently, this is the final post of this blog after more than 400 posts. Read More

Diagnosing and Deciding Military Interventions: Insights from Surgical Scholarship

This blog post was coauthored with my research associate, Jennifer Wilson.

Hillary Clinton has reportedly made reassessing U.S. strategy in Syria one of her first agenda items as president. With a history of generally backing interventions and statements of support for no-fly zones and safe zones on the record, an expanded intervention in Syria is likely should Clinton win. Plenty has been written over the past five years on the the risks and potential benefits of intervening in Syria. Consider how similarly invasive, dramatic, and potentially harmful decisions are made outside of foreign policy: an (admittedly unorthodox) analogy can be drawn between a president’s decision to intervene militarily and a surgeon’s decision to operate on a patient.

Much as government officials can agree on strategic goals but disagree on policies, the decision to operate varies substantially from surgeon to surgeon—even when the same diagnosis is presented to them. To better understand why surgeons decide to recommend surgery, researchers led by Dr. Greg D. Sacks at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine surveyed doctors on their perceptions of risks and benefits of both operative and non-operative management.

In one study, the authors presented 767 surgeons with four clinical vignettes in which the best course of action was not clear. They asked the doctors to judge the risks and benefits of operating and not operating and to decide whether they would recommend surgery. For example, the surgeons were asked to rate how likely an otherwise healthy 19-year-old woman is to face serious complications from an appendectomy, how likely she would be to recover fully, and the prospects of both complications and recovery if she did not go under the knife. As one might expect, surgeons were more likely to recommend an operation when the benefits of surgery outweighed the risks. However, across the four cases the doctors did not agree on whether to operate or not. In the case of the young woman’s appendix, they were split nearly down the middle, with 49 percent recommending surgery. Their decisions were informed by perceptions of risk, and those perceptions varied considerably—as much as 0 to 100 percent.

Of course, defining and quantifying risks is difficult. To attempt to overcome this challenge, the authors conducted another study that exposed 395 surgeons to a “risk calculator,” which uses national data to estimate the likelihood of postoperative complications, then asked them and a control group of 384 to judge risks and decide whether to recommend surgery. The authors hypothesized that, once they saw the data, surgeons’ risk assessments would more closely match the results of the risk calculator, and these assessments would in turn inform their decision to operate. The study confirmed the first hypothesis, but interestingly, on average the surgeons did not differ in their reported likelihood of recommending an operation. In other words, the risk calculator did not influence doctors’ recommendations. Perhaps unconsciously, they altered their judgments of risk and benefits to conform to decisions they had already made upon reading the clinical vignettes—decisions made by intuition rather than by risk-benefits analysis.

The results of these studies provide interesting insights for understanding decision-making. The fact that surgeons, who receive training that is far more homogenous and standardized than that of civilian government officials, can vary so much in their perceptions of risks should serve as a reminder that decision-making is an inherently complicated, contested process.

These findings also raise questions for those interested in decision-making processes outside of the operating room. How do policymakers and pundits diagnose the nature of the conflict in Syria? Would attaching numbers to the likely outcome of certain military missions result in a more agreed-upon course of action? Would individuals’ perceptions, informed by a multitude of factors and experiences accumulated over the course of his or her life, continue to drive decisions? Would an alternative assessment of the risks involved sway a president who has already made up his or her mind? Surgeons receive comparable training and experiences when assessing the outcomes of operative surgery; unsurprisingly, those from dissimilar backgrounds and often no exposure to military operations would come to such different conclusions about whether and how to intervene in Syria or elsewhere.

How the U.S. Military Can Battle Zika

Gabriella Meltzer is a research associate in the Global Health program at the Council on Foreign Relations. Aaron Picozzi is the research associate for the military fellows at the Council on Foreign Relations, a Coast Guard veteran, and currently serves in the Army National Guard.

Two years ago, Americans braced for the imminent arrival of Ebola. The virus was spreading rapidly in West Africa, and ended up infecting 29,000 people and killing 11,000 more in the region. Knowing that it could not be contained by underdeveloped and overwhelmed health systems in Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone, the U.S. military took swift action to mitigate its impact in West Africa and prevent the disease from crossing the Atlantic. Ultimately, only four cases occurred in the United States, resulting in just one fatality.

Today we face a new, more complicated public health menace—Zika, a mosquito-borne disease whose outbreak across Latin America has resulted in women giving birth to children with microcephaly and other debilitating neurological disorders. Strategies that focused on behavioral changes were effective in containing Ebola as transmission only occurs through contact with infected people or objects, but they cannot contain Zika, as individual mosquitos’ movement and feeding patterns cannot be closely monitored or controlled. Ebola infections are also much easier to spot—characteristic symptoms present themselves two to twenty-one days post-infection and there are at least seven WHO-approved, reliable diagnostic tests. With Zika, an estimated 80 percent of those infected remain asymptomatic, and rapid, definitive, and affordable diagnostics still remain in development.

Airport screening tactics used to protect Americans from Ebola, which screened 94 percent of all travelers coming from areas of high infection, cannot be applied to Zika. West African migrants are unable to travel the 4,000 miles across the Atlantic to reach U.S. shores—but Caribbean and Latin American migrants can, and regularly do. As economic conditions in Latin American countries like Venezuela and Brazil worsen, the threat of Zika provides another push for those already looking to make a new life in the United States. The U.S. Coast Guard indicts thousands of these migrants annually, from Southern California to as far east as the Atlantic coast of Florida. There is no need to pass through an airport—any shoreline is a landing point, making universal screening nearly impossible.

The confluence of these factors highlights the necessity for a solution at Zika’s source rather than America’s entry points. However, WHO-member nations have displayed lackluster financial commitment to the fight against Zika. Even if the necessary funds were raised, their dispersal to local public health agencies is a long, arduous process, and vaccine development and approval can take upwards of eighteen months.

Instead, there is another actor with resources at its disposal and capable of providing immediate results in this time of urgency—the U.S. military. Rapidly mobilizing the military to conduct advisory missions, strengthening and developing response systems, in areas of high infection would produce a lasting framework tailored not just towards Zika, but a myriad of potential problems. Brazil has turned to its military for domestic response, not because of an inherent skill in mosquito eradication, but because this rapidly deployable, incredibly flexible workforce could be deputized to combat specific problems. The U.S. military has the same ability. Whether responding to the Japanese earthquake of 2011 or the 2014 Ebola crisis, the U.S. military is very effective in aiding local governments while leaving behind a framework to address future disasters. Of course, any U.S. military presence should be tailored to meet local needs, but by focusing on training foreign militaries and other agencies in disaster management, the United States would be making a long term investment in regional stability, as well as U.S. national security.

This is evidenced by the Obama administration’s recently introduced Global Health Security Agenda, which highlights the importance of cooperative prevention, detection, and response to infectious disease agents. To realize this agenda, vulnerable nations like Brazil and Venezuela need support to develop the necessary capacities and framework to ensure global stability.

In an age of globalization and unpredictability, prevention is preferable to reaction. With trained forces located throughout the western hemisphere, the United States will effectively create a sphere of management and mitigation in its backyard. Be it a health emergency like Zika or Ebola, or a natural disaster such as an earthquake or tsunami, the ability to mobilize a trainable force to respond quickly is crucial. Many of the countries in the heart of the Zika epidemic have weak response systems, governments, and economies. Training and strengthening of response efforts in these countries will help to reassure citizens of stability in times of crisis. This is a long term byproduct of training operations, one that reduces the need for reactive action in the future.

With U.S.-led multinational training and partnership, the current hollow framework in place for disaster response and prevention can be strengthened while simultaneously taking steps to counter Zika. Regional problems are quickly becoming international in the age of globalization, and it is often only a matter of time before issues spurred elsewhere arrive on American shores. By training and empowering foreign nations, the United States will feel the beneficial, long-term effects in not only regional, but global stability.

Red Team at Aspen

Late last month, I was honored to be a speaker at the Aspen Ideas Festival about my book Red Team: How to Succeed By Thinking Like the Enemy. The Festival, which the Aspen Institute began in 2005, invites a wide array of thinkers and doers from around the world to present their research or performances in an unusually scenic environment, and in front of super smart and challenging attendees. At this year’s festival, the big-name speakers included Vice President Joe Biden, Attorney General Loretta Lynch, Secretary of State John Kerry, and IMF chief Christine Lagarde. I learned a great deal from the sessions I attended on food insecurity, criminal justice reform, and the expanding universe—I even got to observe evidence of this at night through high-powered telescopes.

I’m sharing a recording of my presentation at Aspen primarily because it was run by the brilliant veteran journalist James Fallows, who graciously provided a blurb for my book ten months ago. He is the gold standard for making a book talk compelling and relevant for the audience. The question-and-answer session with the audience was also spirited and enlightening, at least for me. Overall, a highlight of my career.

Rogue Justice: A Conversation with Karen Greenberg

Today I spoke with Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law School. We spoke about her comprehensive account of the national security legal debates since 9/11 in her new book, Rogue Justice: The Making of the Security State (Crown, 2016), as well as a new report from the Center on National Security that details all 101 publicly known Islamic State-related cases. Karen also offered her sobering and honest advice for young legal and national security scholars. Follow Karen’s work on Twitter @KarenGreenberg3, and listen to my conversation with one of the most respected and knowledgeable scholars in the world of national security, counterterrorism policy, and civil liberties.

Guest Post: Preventing a Strategic Reversal in Afghanistan

Jared Wright is an intern in the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.

President Barack Obama’s recent announcement that 8,400 U.S. troops will remain in Afghanistan at the end of his administration, nearly 3,000 more troops than his previous timeline, reflects the tenuous stability that Afghanistan has achieved after nearly fifteen years of U.S. involvement. A resurgent Taliban and the appearance of self-proclaimed Islamic State forces have tested the ability of the increasingly fragile central government to provide security and political stability and demonstrated the limits of U.S. training and support. Meanwhile, economic and political frustrations across all levels of Afghan society have gone largely unaddressed by the National Unity Government (NUG). The security situation in Afghanistan could worsen, which would threaten U.S. interests in the region.

A new Contingency Planning Memorandum released by the Center for Preventive Action, “Strategic Reversal in Afghanistan,” assesses the growing risks of strategic reversals in Afghanistan. Author Seth G. Jones, Director of the International Security and Defense Policy Center at RAND, recommends steps the United States can take to mitigate or prevent such risks.

The report highlights the shortcomings of the NUG and the challenges that the Afghan National Army and the Afghan National Police—which both face rising attrition rates, low morale, and a climbing death toll—are forced to confront in providing for Afghanistan’s security. Jones identifies two principle contingencies to watch over the next twelve to eighteen months: the collapse of the NUG—which is plagued by widespread corruption, deteriorating economic conditions, and competition among Afghan elites—and major gains in urban areas by the Taliban, who now control more territory than at any other point since December 2001. Both outcomes are not mutually exclusive, as one contingency would ultimately magnify the potential for the other.

U.S. interests would be harmed if either contingency happens. U.S. objectives in Afghanistan are clear: to target al-Qaeda and other extremist elements in order to prevent future attacks against the United States, and to enable Afghan forces to provide security for the country. A government collapse or the seizure of one or more major cities by the Taliban would severely diminish the likelihood of achieving either objective, while simultaneously rolling back gains made over the last decade. These contingencies could also lead to an increase in extremist groups operating in Afghanistan; introduce regional instability involving India, Pakistan, Iran, and Russia; and possibly signal to other countries that the United States is not a reliable ally, further complicating regional power dynamics.

To prevent these contingencies from occurring, Jones recommends the United States leverage its relationship with Afghanistan, focusing on building greater political consensus, encouraging regional powers to support Kabul, pursuing reconciliation with the Taliban, and strengthening Afghan security forces so that they can manage internal security challenges with limited outside involvement. To achieve those aims, the U.S. should:

Focus diplomatic efforts on resolving acute political challenges, prioritizing electoral reforms and building consensus between the Afghan government and political elites.

Address economic grievances that could undermine the political legitimacy of the government.

Sustain the current number and type of U.S. military forces through the end of the Obama administration.

Decrease constraints on U.S. forces in Afghanistan and grant the military authority to strike the Taliban and Haqqani network.

Sustain U.S. support for the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces.

For a more in-depth analysis on how the situation in Afghanistan might result in a strategic reversal and what the United States can do to prevent that from happening or mitigate the consequences, read “Strategic Reversal in Afghanistan.”

Online Store

Online Store